Executive summary

I The EU established a framework for screening foreign direct investment in 2020. Regulation (EU)¬Ý2019/452 (‚Äòthe Regulation‚Äô) establishes a framework for the screening by member states of foreign direct investment and a cooperation mechanism among EU member states and the European Commission to assess and potentially restrict foreign direct investment that may pose a threat to security or public order in the EU or its member states.

II The Regulation aims to ensure a coordinated approach to the screening of foreign direct investment in strategic sectors that are vital for the security and functioning of the EU's economy. Foreign direct investment in the EU amounted to approximately ‚Ǩ117¬Ýbillion in 2021 in terms of inflows (8¬Ý% of the world level). It provides for a cooperation mechanism which takes account of the EU dimension of foreign direct investment cases handled at national level by identifying their cross-border impacts, and addresses security and public-order risks to EU projects and programmes. The Regulation also recognises that certain foreign investments may have implications for critical infrastructure, technologies, or sensitive information, and seeks to safeguard EU interests in these areas.

III The main objective of this audit was to assess whether the EU framework for screening foreign direct investment (including the cooperation mechanism) is efficient and effective at addressing security and public-order risks. We examined both its design and its implementation by the Commission, reviewed a representative sample of cases notified by member states and assessed by the Commission, and all opinions the Commission issued between 2020 and 2022. The audit scope did not include the member states’ screening laws and decisions.

IV Overall, we conclude that the Commission has taken appropriate steps to establish and implement a framework for screening foreign direct investments in the EU. However, there remain significant limitations across the EU that reduce the effectiveness and efficiency of the framework at preventing security and public-order risks. Six member states do not have a screening mechanism and there are differences in terms of scope, coverage in terms of defining critical sectors and understanding of key concepts. This creates multiple blind spots compromising the effective protection of the entire EU. Improvements are also necessary in the Commission’s assessments and recommendations.

V Specifically, in terms of preventing risks to security and public order at EU level, the current framework is partially appropriate. To a certain extent, cooperation provided member states with information on foreign direct investment being screened, and gave them an opportunity to share concerns and address them together when necessary. However, the enabling rather than harmonising nature of the Regulation’s design results in inherent limitations to the effectiveness of risk identification and uniform screening. The Regulation does not have sufficiently clear provisions to ensure that key concepts are always interpreted consistently and that comparable rules are applied to comparable situations with the ultimate goal of avoiding undue restrictions to the free movement of capital and rights of establishment (e.g. in terms of intra-EU investment by foreign investors, the inclusion of indirect foreign investment, and the exclusion of portfolio investments).

VI We also found that there are significant divergences across the screening mechanisms of member states, and that the Commission has not completed any formal assessment of its compliance with the minimum conditions set in the Regulation. Member states do not provide any preliminary eligibility and risk assessments of the cases they notify. This leads to a high volume of low-risk or ineligible cases, which overburden the cooperation mechanism.

VII We found that the cooperation mechanism, and in particular the Commission’s eligibility and risk assessment, together with the quality of its opinions and related recommendations, is partially effective at adequately mitigating the risks posed by foreign direct investment at EU level. Although the assessments identify risks, and contribute to forward-looking thinking on potential vulnerabilities, we identified issues in the Commission’s assessments and aspects of the recommendations which may raise challenges for enforceability, or be inconsistent with a market-economy environment.

VIII We found that the Commission has implemented appropriate operational tools, IT systems and resources to handle the current case load arising from the cooperation mechanism on a timely basis and within the tight deadlines stipulated in the Regulation. It has also produced its annual reports as required by the Regulation. Nevertheless, we identified some room for improvement across these functions with a view to focusing on systemic issues and approaches that are relevant at EU level. Specifically, the Regulation does not require feedback from member states on their screening decisions that would enable the Commission to monitor and report on the effectiveness of the screening framework.

IX In view of the above, we recommend that the Commission should:

- seek the necessary amendments in the Regulation to strengthen the EU foreign direct investment screening framework by clarifying the key concepts of the framework and avoiding the current blind spots and inefficiencies;

- assess national screening mechanisms for compliance with regulatory standards, and streamline some practices like pre-screening and aligning criteria, timeframes and processes across member state screening mechanisms;

- improve the cooperation mechanism and the Commission’s assessments for providing better justification of mitigating actions related to high-risk cases; and

- improve the reporting process.

Introduction

01 Openness to foreign direct investments (FDI) has been and continues to be one of the key principles of the internal market. The EU Treaties1 define common commercial policy as contributing to the harmonious development of world trade, the progressive abolition of restrictions on international trade and on FDI, and the lowering of customs and other barriers. However, perceptions have changed as a result of concerns about lack of reciprocity and the new geopolitical environment, including an increasing awareness of the vulnerabilities stemming from the EU’s dependencies.

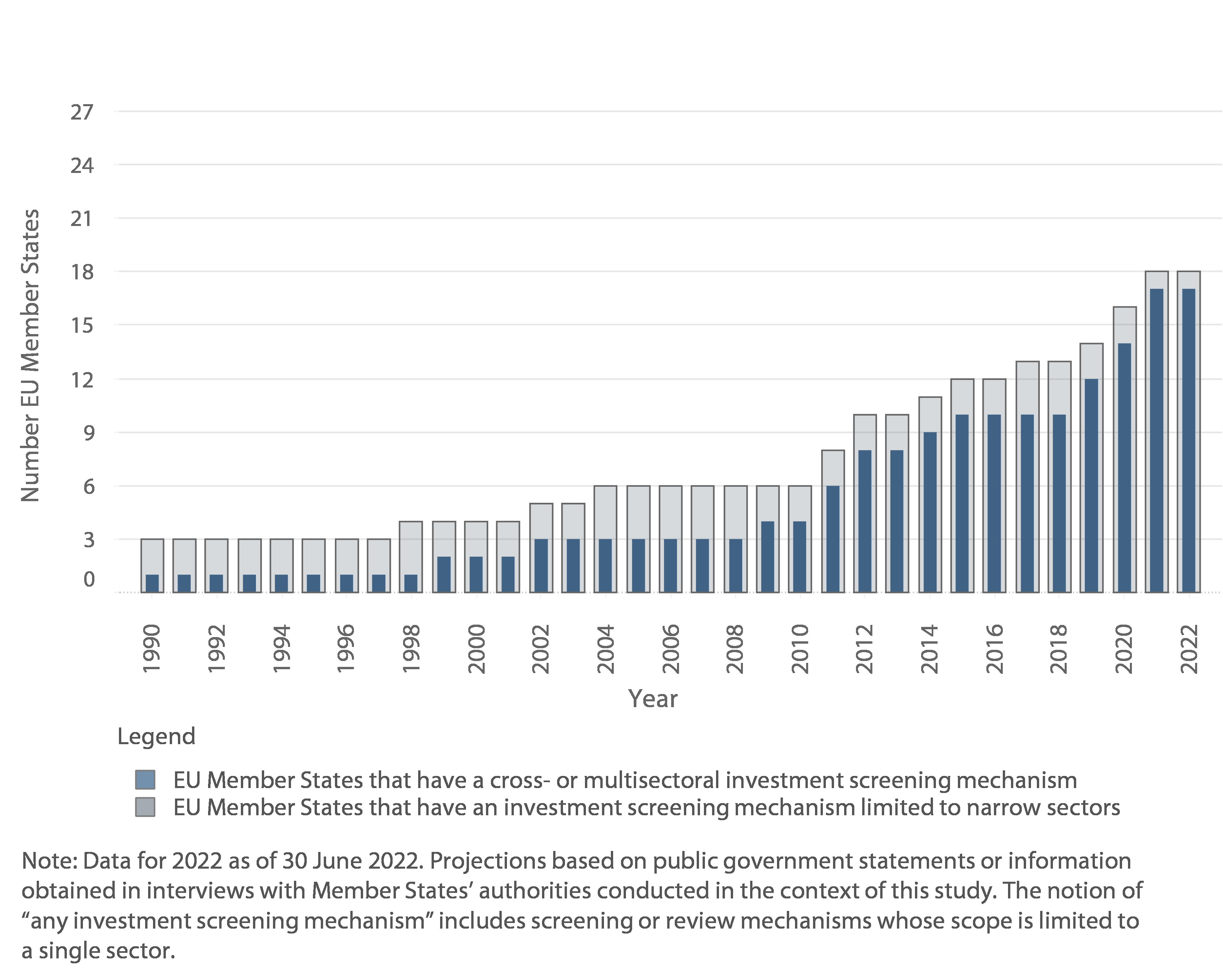

02 In line with global developments, EU member states and the EU have taken steps to better protect themselves against the potential dangers relating to FDI. Figure¬Ý1 provides an overview of the evolution of the number of member states with screening mechanisms in the EU (see also paragraph¬Ý06).

Figure¬Ý1 ‚Äì Evolution of investment screening mechanisms in the EU member states (1990-2022)

¬©¬ÝOECD, 2022: Framework for Screening Foreign Direct Investment into the EU ‚Äì Assessing effectiveness and efficiency.

03 Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an investment of any kind by a foreign investor aiming to establish or to maintain lasting and direct links between the foreign investor and the entrepreneur to whom or the undertaking to which the capital is made available in order to carry on an economic activity in a member state, including investments which enable effective participation in the management or control of a company carrying out an economic activity2. A foreign investor is a natural person or an undertaking privately or publicly owned, of a third country (i.e. outside the European Union).

04 The EU had inward FDI totalling ‚Ǩ117¬Ýbillion in 2021, i.e. 8¬Ý% of the world total level3. FDI is widely considered as beneficial for host and home economies and for the enterprises that carry out the investments. It can, for example, enhance growth and innovation in host countries, contribute to creating quality jobs and developing human capital, raise living standards and help spread good practice in management and with regard to responsible business conduct.

05 However, risks associated with FDI have become more serious, especially in cases concerning strategic autonomy and assets (e.g. nuclear plants or ports), sensitive sectors (e.g. those involving critical defence inputs such as semi-conductors or microchips of a dual-use nature), or the transfer of sensitive technology to a third country whose strategic intents are not aligned with EU interests. Box¬Ý1 provides a summary of the main factors affecting security and public order, as listed in Article¬Ý4 of Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452. Box¬Ý2 provides an example of a potentially harmful FDI.

Main factors affecting security and public order, as listed in Article¬Ý4 of Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452

The Regulation does not define the terms ‘security’ or ‘public order’ but lists factors that member states or the Commission may take into account in determining if a FDI is likely to affect security and public order. These include:

- the critical nature of the target:

- critical infrastructure to which a foreign entity could cause disruption (public order) and pose a risk to national security;

- critical technologies and dual -use items (including artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, cybersecurity, aerospace, defence, energy storage, quantum and nuclear technologies, as well as nanotechnologies and biotechnologies);

- the supply of critical inputs, including energy or raw materials, as well as food security;

- access to sensitive information, including personal data, or the ability to control such information; and

- the freedom and pluralism of the media;

- the critical nature of the foreign investor:

- directly or indirectly controlled by the government, including state bodies or armed forces of a third country;

- prior involvement in activities affecting security or public order in a member state; or

- engagement in illegal or criminal activities.

Example of potentially harmful FDI

The acquisition of a research-driven industrial engineering EU company and design house specialising in radio technologies and microelectronics by a state-owned defence company from a third country.

06 Investment screening mechanisms (i.e. legal and administrative instruments that allow FDI to be assessed and investigated before authorisation with or without conditions or even prohibition) can be traced back to the 1960s in some countries. The introduction of such rules allows governments to scrutinise individual investment proposals for their potential impact on essential security interests. Until very recently however, many countries did not have investment screening mechanisms in place and were relying instead on single-sector authorisation requirements or similar mechanisms at most. For many years, few countries had legislated in this area – introducing new mechanisms or reforming existing ones – until policymaking activity surged in and after 2016.

07 The European Parliament launched a debate as early as 20124 in response to global trade developments and specific transactions in strategic sectors, mainly as an approach to security and defence matters. In February¬Ý2017, the governments of France, Germany and Italy voiced concern about third-country investments, particularly in cases where state-owned enterprises investing as part of a strategic industrial policy acquired critical assets and key technologies from EU companies, but did not offer reciprocal rights to invest in the country from which the FDI originated. The three member states recognised that EU law already allowed ‚Äúmember states to prohibit foreign investments which threaten public security and public order‚Äù, and 11¬Ýmember states already had a screening mechanism in place. However, given the Commission‚Äôs expertise, they called for additional protection based on economic criteria. This debate was seen as a way to defend European interests in a hostile geopolitical environment.

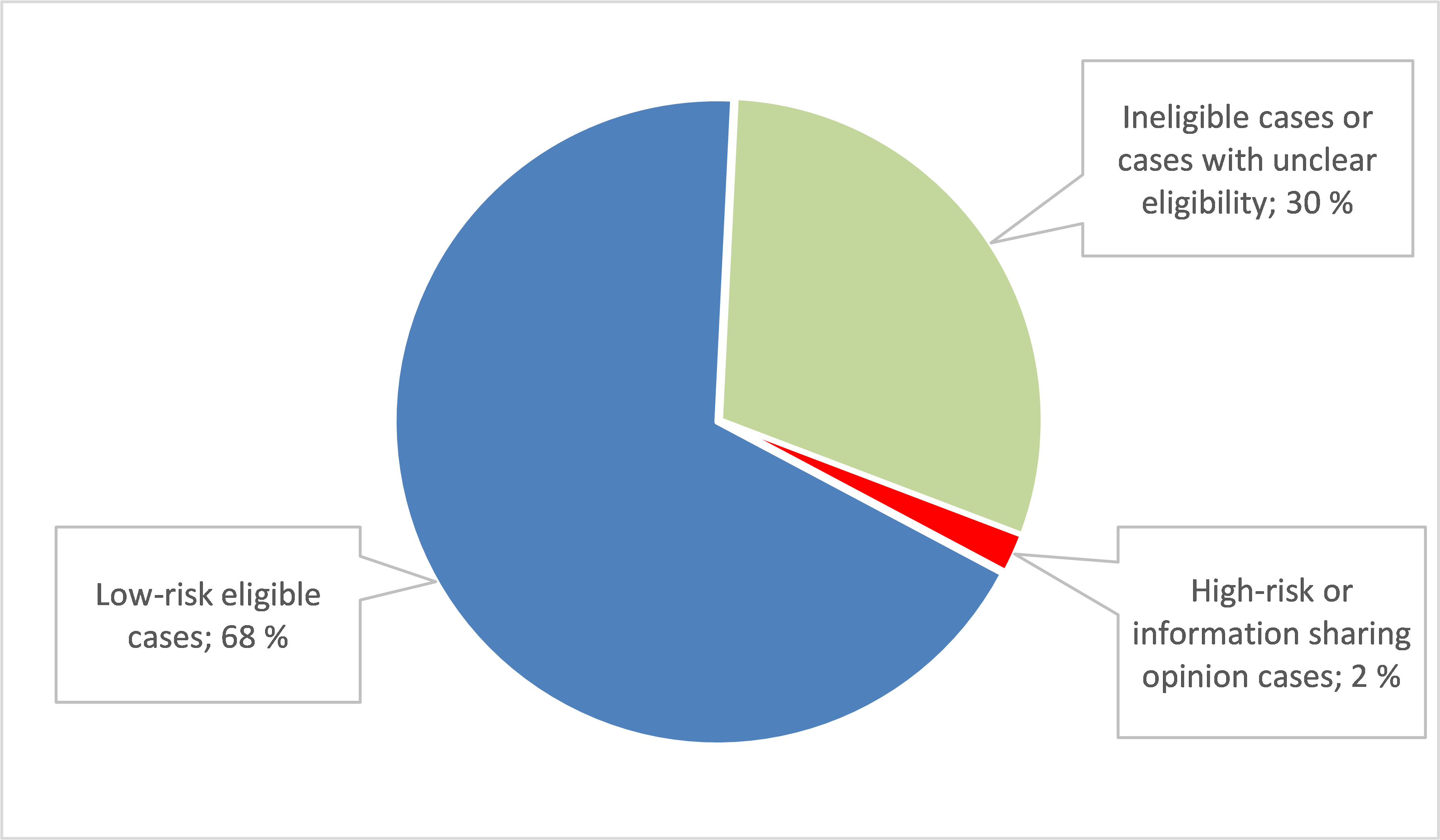

08 In May¬Ý2017, the Commission proposed establishing a framework for member states and the Commission to screen FDI in the EU, while allowing member states to take their individual situations and national circumstances into account5. On¬Ý13¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2017,¬Ýthe Commission¬Ýpublished a proposal for a regulation establishing a legal framework for the screening of FDI inflows into the EU. In 2019, the European Parliament adopted the proposal, and the Council formally endorsed it in March¬Ý2019. Thus, Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/4526¬Ý(‚Äòthe Regulation‚Äô) became applicable on 11¬ÝOctober¬Ý2020.

09 Major trading nations across the world have FDI screening mechanisms with differences in their respective scope and powers, governance structures, sectoral emphasis, or obligations and penalties for investors and targets. For example, the United States has a centrally managed framework, run by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). For more details, see Annex¬ÝI. However, while similar principles may apply, screening across the EU poses a number of challenges that do not exist in countries where screening is limited to one jurisdiction. The US framework is more comparable to member states‚Äô screening mechanisms in terms of its scope and powers.

Scope and objectives of the Regulation

10 The Regulation establishes a cooperation mechanism among EU member states and the European Commission to assess and potentially restrict FDI that may pose a threat to security or public order in the EU or its member states. It aims to ensure a coordinated approach to the screening of FDI in strategic sectors that are vital for the security and functioning of the EU's economy. The Regulation recognises that certain foreign investments may have implications for critical infrastructure, technologies or sensitive information, and seeks to safeguard EU security and public order.

11 The Regulation was established using the EU‚Äôs exclusive competence for common commercial policy, in particular with regard to foreign direct investment pursuant to Article¬Ý207 (2) TFEU. However, national security and public order are an area that is the sole responsibility of member states. Therefore, member states are free to introduce a screening mechanism and define its scope as long as they comply with EU law (including free movement for capital) and member state‚Äôs authorities are the only ones that can take decisions on individual foreign direct investments.

12 The key elements or mechanisms envisaged in the Regulation are the following:

- screening mechanisms of member states;

- cooperation mechanism in relation to FDI; and

- Commission’s assessment of FDI likely to affect projects or programmes of Union interest (ex officio).

13 The aim of the Regulation is to ensure that the EU and the member states are better equipped to identify, assess and mitigate potential risks to security or public order deriving from FDI. For that purpose, the Regulation:

- lays down certain requirements for those member states that wish to maintain or adopt a screening mechanism at national level. Regardless of whether they have a formal screening mechanism in place, member states have the last say on whether a specific investment operation should be allowed on their territory (Articles¬Ý3 to 5);

- creates a cooperation mechanism where member states and the Commission are able to exchange information, request further information when necessary, and raise concerns about specific investments Articles¬Ý6 to 7);

- takes account of the need to operate under short business-friendly deadlines and strong confidentiality requirements;

- allows the Commission to issue opinions when it believes an investment threatens the security or public order of more than one member state, or when an investment could undermine a strategic project or programme of interest to the EU as a whole, such as the EU‚Äôs research and innovation programme or Galileo7 (Article¬Ý8); and

- encourages international cooperation8 on investment screening, including sharing experience, best practices and information on issues of common concern.

14 The Regulation does not operate in isolation, but is part of a larger toolkit that regulates FDI inflows into the EU single market and outflows to external markets. It works in conjunction and shares objectives with other EU policies that potentially apply to the same transactions from different perspectives and legal positions. For example, EU dual-use technologies can be transferred not only by buying EU undertakings by third countries, but also by exporting goods to third countries or when EU undertakings acquire subsidiaries outside the EU. For this reason, Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2021/821 sets up an EU regime for the control of exports, brokering, technical assistance, transit and transfer of dual-use items. Other examples are EU antitrust and competition policy and its control systems and the new rules on distortive foreign subsidies (Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2022/2560).

Main players and the process for screening FDI in the EU

15 The main players are the member state authorities tasked with screening FDI, and the Commission (mainly through DG¬ÝTRADE). The ECA has already pointed out in a specific case (see ECA review¬Ý03/2020: The EU‚Äôs response to China‚Äôs state-driven investment strategy) that in policy areas where the EU and member states both exercise competences, a concerted EU approach could be an advantage. However, the fact that both the EU and member states exercise competences means that there are possible diverging opinions and approaches. This could make it difficult to address the challenges faced by the EU as a whole in a timely and coordinated manner.

16 Member states are free to decide whether or not they want to introduce FDI screening mechanisms. However, once a member state establishes a screening mechanism, it is also responsible for reporting FDI cases undergoing screening to the Commission and other member states through the cooperation mechanisms stipulated in the Regulation. The timelines for the screening process in member states vary from two months in Malta to six months in Germany9. Member states are required to submit annual reports to the Commission that include information on the FDI that took place on their territory in the preceding year, and any requests received from other member states as part of the cooperation mechanism and the operation of their national screening mechanism.

17 The Commission has the following responsibilities10:

- publishing and maintaining an up-to-date list of screening mechanisms established in member states;

- managing the cooperation mechanism for FDI cases undergoing screening;

- assessing all FDI cases reported by member states;

- issuing opinions for those cases it considers likely to affect security or public order in more than one member state, or to projects or programmes of EU interest;

- issuing opinions when it has relevant information on a particular FDI, whether or not that FDI is undergoing screening;

- securing the rights and freedoms of foreign investors to establish and move capital within the EU;

- ensuring that EU international agreements regarding foreign direct investment are complied with; and

- submitting an annual report to the European Parliament and the European Council on the implementation of the EU FDI Screening Regulation11.

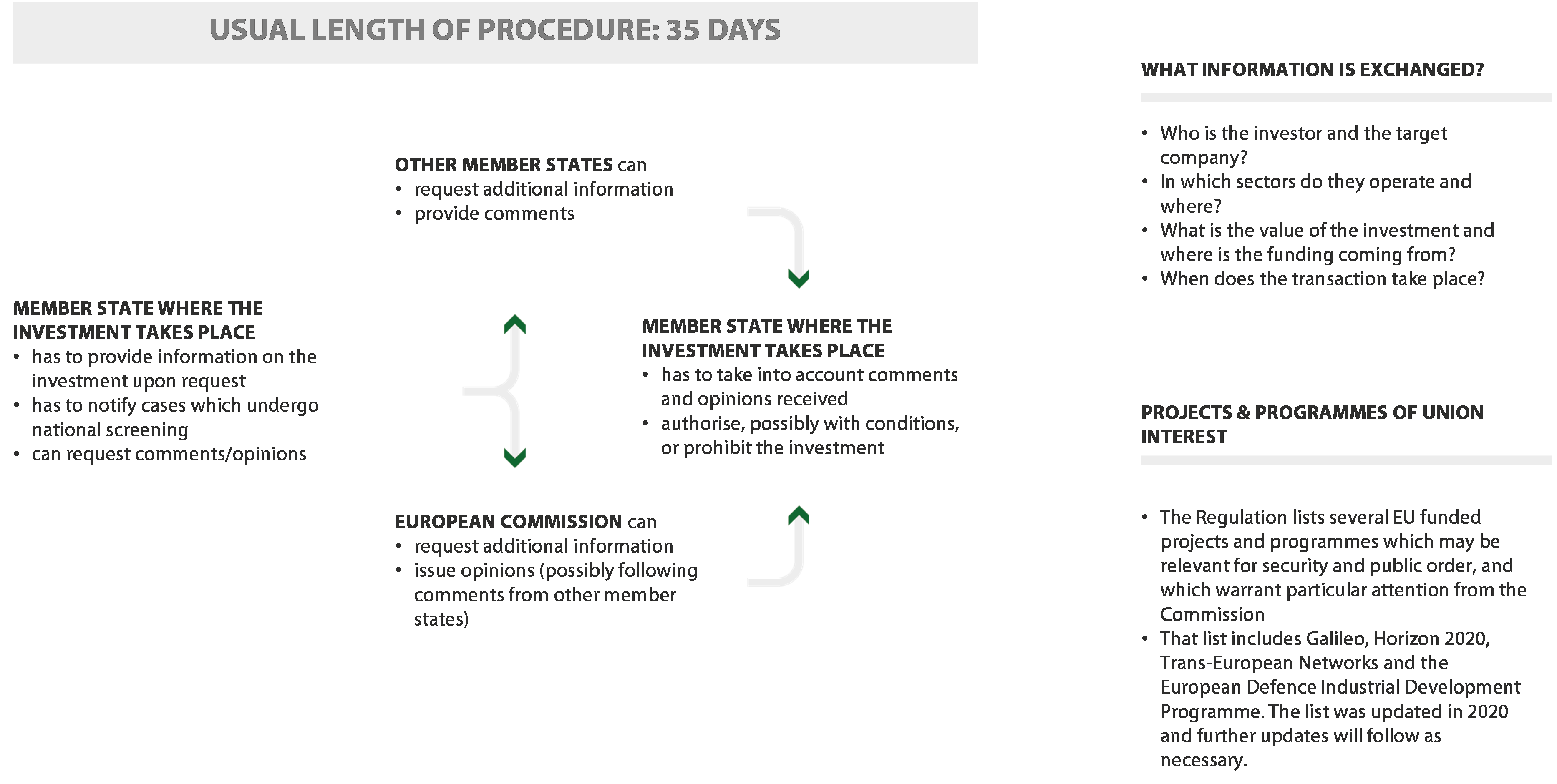

18 Figure¬Ý2 summarises the framework for screening FDI in the EU.

Source: European Commission.

Audit scope and approach

19 The main objective of this audit was to assess whether the EU framework for FDI screening (including the cooperation mechanism) is efficient and effective at addressing security and public-order risks. The audit covered the period from the adoption/enactment of the FDI regulation until September 2023. The audit should also serve as an input for the Commission’s review of the framework and the accompanying legislative proposal.

20 We examined the design and implementation of the EU framework for FDI screening (including the cooperation mechanism) that was set up under Regulation (EU)¬Ý2019/452. We assessed whether:

- the regulatory framework is appropriate for protecting against security and public-order risks derived from FDI;

- the FDI screening mechanisms in place comply with the regulatory framework, and are appropriate for addressing consistently the FDI risks to security and public order;

- the mechanisms for cooperation between member states and the Commission are appropriate for addressing FDI risks to security and public order; and

- the Commission allocated the necessary resources, and implemented the appropriate operational tools and reporting, to ensure efficient FDI screening and cooperation (operational efficiency of the Commission).

The observations presented in the subsequent sections follow the order of the points set out above.

21 The audit criteria were derived from applicable legislation, including the EU Treaties, World Trade Organization agreements12, case law of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), principles of sound financial management as well as¬Ýfrom relevant documents issued by the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament, and from international best practices, including those of international organisations.

22 Specifically, we:

- conducted interviews and meetings with EU officials, mainly at DG¬ÝTRADE which has primary responsibility for FDI screening;

- reviewed and analysed a random and representative sample of 30 cases reported to the cooperation mechanism, plus a risk-based sample of cases analysed by the Commission, including ex officio cases and all those which resulted in a Commission opinion covering the period 2020 to 2022;

- reviewed and analysed relevant Commission guidance to member states, as well as internal guidelines and checklists;

- conducted interviews with six member state authorities, taking into consideration the size of the economy and geographical balance (Germany, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden);

- surveyed the responsible authorities in all member states (25 of which replied); and

- consulted publicly available documents issued by relevant authorities, the OECD and other international organisations, and academics.

23 The audit scope did not include the assessment of member state screening laws, procedures and decisions. As the cases and other underlying documents we analysed are classified as “EU-restricted” and cannot be disclosed publicly, we provide only summary information that highlights specific problems, but without further details or specific examples.

Observations

The FDI screening framework enhanced cooperation, but its limitations reduce its effectiveness

24 To have an effective system, it is important to cover all relevant types and forms of investment and investors, and security and public order risks. The EU framework for FDI screening should be able to prevent circumvention and avoid security and public order criteria being used to apply protectionist measures. A balance should be struck between FDI screening detection and the mitigation of risks to security and public order on the one hand, and the openness of the EU to FDI on the other.

25 When determining and interpreting the definitions of key concepts in the Regulation, the Commission should take account of the principles enshrined in the EU treaties, in particular with regard to free movement of capital and commercial policy, and the competences of the EU and its member states on FDI, security and public order. There should therefore be clear definitions of the main elements and concepts relating to FDI and FDI screening in the Regulation, and these should be compatible with existing jurisprudence.

A first step in FDI screening and cooperation, but inherent limitations remain

26 We found that the cooperation mechanism established for the first time by the Regulation enables member states and the Commission to share screening information and risk assessments on FDI. This provides the member state that screens and authorises FDI with information on potential risks for other member states, or on risks posed to EU projects or programmes. The framework is thus a positive step, making it possible to detect risks that may otherwise go undetected given the complexity of ownership structures, state influence, criminal intent, or cross-border vulnerabilities and critical dependencies. Our survey confirmed that it also helps to develop a better understanding of investment trends in Europe and promote closer cooperation and peer learning among member state authorities in this area.

27 However, the framework also faces inherent limitations due to its design and to EU competences that limit its effectiveness at preventing security and public-order risks by allowing for blind spots that compromise the effective protection of the EU as a whole. The following are issues pointing at such limitations:

- the Regulation is an enabling rather than a harmonising framework. It authorises, but does not oblige, member states to introduce national rules that govern FDI screening;

- the member states have the option of determining the scope of their mechanisms in important areas such as what investments to screen; how to establish the notion of control by a third-country entity; which sectors to include as critical for security or public order; and even whether to screen FDI at all;

- the Commission cannot prohibit FDI transactions, or impose any binding condition upon them, even when EU interests are at stake;

- member states cannot block FDI in another member state, nor are they obliged to heed other member states’ concerns;

- member states are not obliged to inform the Commission or other member states of the final decisions taken on specific FDI transactions;

- although the Commission may assess FDI which is not undergoing screening, these provisions have a limited added value, given the lack of information available on the FDI transactions taking place, except for that available in the public domain.

28 Figure 3 shows the situation in September 2023, when 21 member states had a screening mechanism in place. The Commission considers it important for all member states to have a national screening mechanism, especially in the context of the Single Market13.

Figure 3 – Screening mechanisms in EU member states (2023)

Source: ECA, based on the Commission‚Äôs¬Ý2022 annual report and updated information up to September¬Ý2023.

The Regulation does not define key concepts clearly, or provide for feedback

29 The Regulation does not have sufficiently clear provisions and definitions of key concepts. We found that this negatively affects the efficiency and effectiveness of EU-wide screening and exposes member states to unnecessary legal risks. The following are examples of these shortcomings:

- no uniform interpretation of ‚Äúlikely‚Äù. We saw in our audit work that this interpretation currently differs between member state FDI screening authorities. As long as the Regulation remains vague, only the CJEU can ensure a uniform interpretation. In our view, the notion of ‚Äúlikelihood‚Äù as used in the Regulation (Article¬Ý4(1)) is vague and does not consider the potential impact of the risk, nor does it ensure that member states apply it consistently. In addition, it is not aligned with the notion of a ‚Äúgenuine and sufficiently serious threat‚Äù to a fundamental interest of society, as currently established by the CJEU, which also stated that restrictions cannot be applied to serve purely economic ends14;

- the risk that restrictions constitute a means of arbitrary discrimination, and that the same rules are not applied equally to comparable situations. An investment from a third country enjoys the same freedom as an investment from within the EU, and any restrictions are prohibited except on grounds of security or public order. Consequently, any investment screening for security or public order should be neutral to an investment’s origin (whether from within the EU or from third countries) in order to avoid discrimination. The Commission currently considers intra-EU trade only in cases of suspected circumvention. Against this backdrop, the cooperation mechanism cannot be used to assess risks from foreign investment channelled through intra-EU acquisitions (i.e. when the European investor is held or controlled by a foreign investor). In our view, the fact that this approach is not made clear in the Regulation means that there is still exposure to risks from foreign investment channelled through intra-EU acquisitions (i.e. when the ultimate beneficial owner is a third country controlling an EU entity). While within national screening mechanisms, we observe different practice in different member states in this respect;

- member states do not provide sufficient information on the outcome of cases to allow the Commission to evaluate the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation. As the Regulation does not require member states to report the outcomes of cases undergoing their national screening procedures to the Commission, the Commission lacks the necessary authority to obtain information in order to comply with its obligation to evaluate the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation and make this information available to the European¬ÝParliament and the Council. As the guardian of the Treaties, the Commission has also to ensure that investors are not discriminated against, or that the free movement of capital is not unduly restricted as a result of member state screening of FDI;

- unclarity whether indirect investment being screened lies within the scope of the Regulation. For example, the Commission and most member states apply the cooperation mechanism to cases where the investor, the seller and the direct target are established outside the EU if a subsidiary of the direct recipient of the investment is within the EU. In our view, the Regulation’s definition of ‘foreign direct investment’ is not clear in this respect, and allows for differing interpretations and screening practices, which does not ensure a uniform approach across the EU. Another example is investments by EU citizens who have acquired citizenship through the ‘golden passport’; these are considered to lie outside the scope of the Regulation. Even though this loophole may be used by investors to circumvent the rules, the issue is not addressed by the current Regulation;

- portfolio investments are not treated equally by everyone, i.e. outside the scope of the Regulation. While portfolio investments are considered to lie outside the scope of the Regulation15, Article¬Ý2 does not define what constitutes a portfolio investment. The CJEU has described ‚Äòportfolio investments‚Äô as ‚Äúthe acquisition of shares on the capital market solely with the intention of making a financial investment without any intention to influence the management and control of the undertaking‚Äù16. However, our assessment of a sample of cases showed that portfolio investments had been screened.

Effectiveness of the framework affected by a lack of compliance assessment and differences in member states’ FDI screening mechanisms

30 In order to ensure the effectiveness of the framework, screening mechanisms should comply with the minimum criteria set out in Articles¬Ý3, 4 and 6 of the Regulation, and the Commission needs to assess compliance with these criteria in order to assess the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation. Among other things, member states setting up FDI screening mechanisms are required to:

- report all cases that are being screened to the cooperation mechanism, and provide the minimum information required by Article¬Ý9;

- inform investors that their cases are being processed;

- provide investors with explanations for their investments being blocked, and be able to appeal against decisions by member state authorities.

31 The Regulation aims to establish a set of uniform principles for FDI, and prohibits screening from being used as a barrier to free trade under the pretext of security or public order. Moreover, member states should report cases which reflect potential risks, and should provide sufficient and relevant information for other member states and the Commission so that they can assess risks to their security and public order.

No Commission assessment to ensure that screening mechanisms comply with the standards stipulated in the Regulation

32 Article¬Ý3 of the Regulation provides a set of common standards for screening mechanisms in the EU, and requires the Commission to maintain an updated list of the mechanisms in place. We found that the Commission maintains and publishes a list of screening mechanisms on its website, and provides a summary in its annual report17. It¬Ýalso co-financed a study carried out by the OECD, which resulted in an extensive overview of the different aspects of national screening mechanisms without having to provide an assessment of their compliance with the requirements of the Regulation. The Commission itself has not produced its own assessment of whether national screening mechanisms comply with the requirements of Article¬Ý3 of the Regulation to be able to assess the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation. Therefore, there is no verified information available on to what extent member states comply with these requirements and how this affects the effectiveness and efficiency of the framework.

Significant differences between member states’ FDI screening mechanisms make the framework less effective

33 The OECD study which received financial support from the Commission in 2022, highlights a number of significant differences between national screening mechanisms. These differences18 have an impact on how effective and efficient the system is at mitigating threats to security and public order as they create blind spots and in some cases seem not to be fully in line with the Regulation. These include:

- differences in the sectoral scope of the mechanisms, with only a few member states able to screen transactions across any sector, while others are based on lists of sensitive sectors or specific assets;

- differences in exemptions for certain acquirers, with many member states exempting EFTA, non-EU EEA Members, NATO, or other OECD members ‚Äì 20¬Ýjurisdictions in all ‚Äì from applying part of their screening mechanism;

- different concepts of security and public order, where some member states still continue to refer explicitly to Articles¬Ý52 and 65¬ÝTFEU, which has been interpreted narrowly in the CJEU‚Äôs jurisprudence and could lead to under-use of the cooperation mechanism;

- different notification dates and timelines for multi-jurisdictional cases being applied across member states;

- differences in terms used to indicate the likelihood of risks, using wording such as “disrupt”, “threaten”, “pose a risk”, or “may affect”;

- different thresholds when determining control, such as shareholdings or voting rights required, which can be 10¬Ý%, 25¬Ý%, or 50¬Ý% plus one vote19;

- differences in powers to consider threats to other EU member states, with only a few member states’ screening laws containing explicit powers to act in the interest of other member states, or projects or programmes of EU interest20.

34 Our audit (interviews, survey and analysis of the sample of cases) confirmed the differences highlighted by the OECD. In addition, we found that the following issues had a negative impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of FDI screening at national and EU level:

- differences in determining the scope of certain types of investment. Namely, the Commission applies the EU framework to cases where the acquisition of an EU target involves direct investment by entities established outside the EU. However, we found that practices differed between member states. Some exempt certain foreign investors based on their nationality (e.g. EEA countries), while others even screen investors or entities that reside or have a seat in the EU, or screen investments made by EU persons and undertakings;

- pre-screening used in some member states:

- Article 6(1) of the Regulation requires member states to report any FDI that is undergoing screening. However, we found that some member states use an initial risk assessment referred to as “pre-screening” to decide whether or not to screen, resulting in notifications for only a subset of the cases they actually review;

- the Commission has not yet required member states to provide notification of all cases undergoing screening, as stipulated by Article 6(1) of the Regulation, while the Regulation does not distinguish between phases of FDI screening which would exempt such early stage screening;

- different treatment of multi-jurisdictional cases:

- in certain cases, an acquisition of a group with subsidiaries across the EU may lead to notifications from several member states. We found that different notification filing dates by investors – or different national procedures – create additional challenges for screening multi-jurisdictional cases. For example, in one of the cases we reviewed, a gap resulted when investors did not provide notification in the member state of the EU parent target, but did provide notification in other member states for the EU subsidiaries;

- we also found that the Commission makes an effort to assess such multi-jurisdictional cases as comprehensively as possible. However, the Regulation contains no provisions for streamlining processes across the EU.

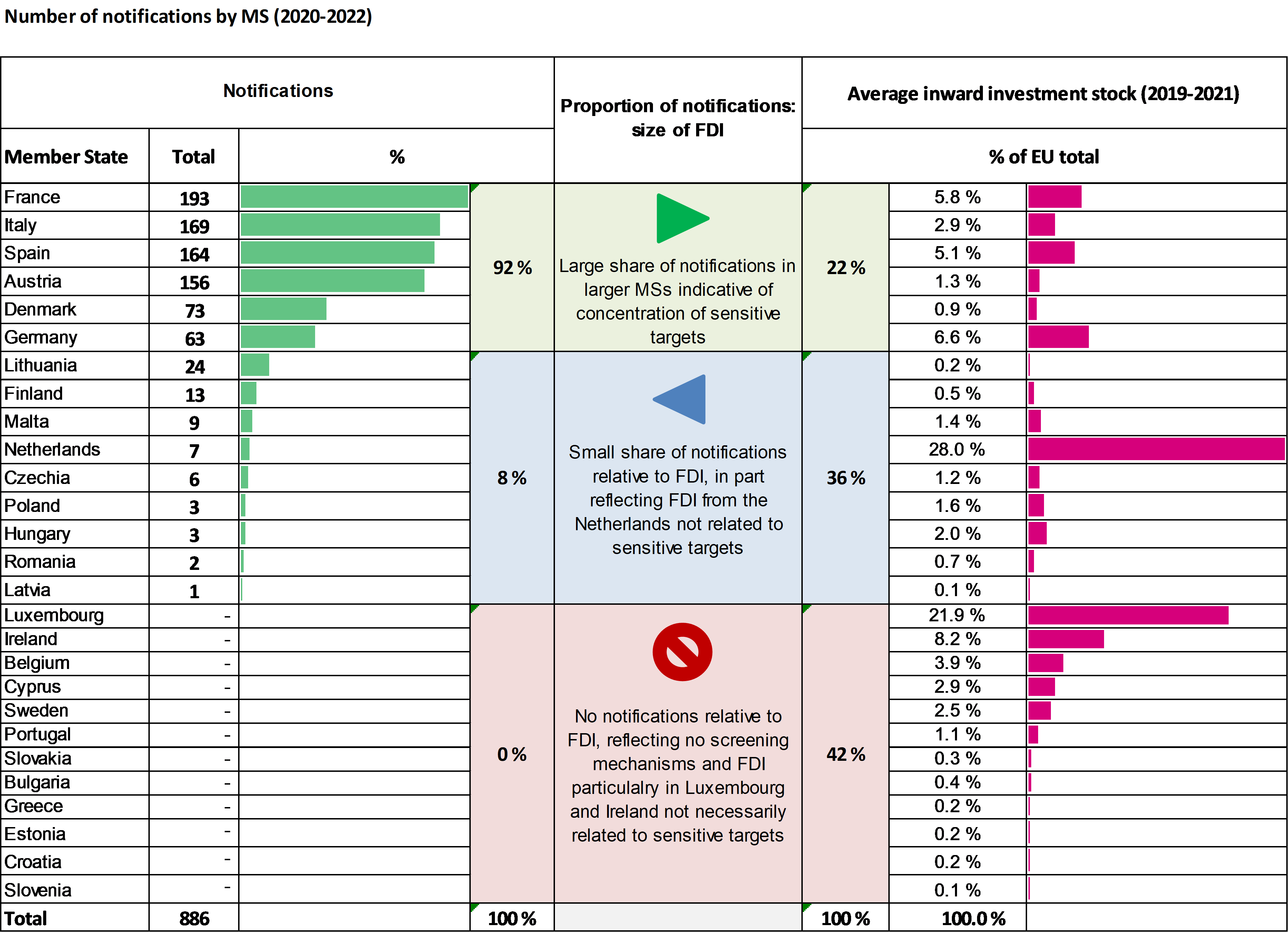

35 The differences cited above also contribute to an uneven distribution of notifications between member states and limit the effectiveness of the framework. Figure¬Ý4 shows the aggregate number of notifications submitted by groups of member states in 2020 to 2022, and their respective FDI stock, based on 2019-2021 data. We would expect a level of correlation which did not actually materialise, between the size of economies, the level of inward FDI and the number of notifications. Six member states together submit 92¬Ý% of all cases, whereas a second group of nine member states with screening mechanisms submit the remaining 8¬Ý%. A third group of 12¬Ýmember states did not screen or provide notification of any cases in the same period; these member states account for approximately 42¬Ý% of the EU‚Äôs average FDI stock. In our view, this has a significant impact on the effectiveness of the framework and limits the overview that the Commission and other member states could have.

Figure¬Ý4 ‚Äì Notifications (2020-2022) compared to average FDI stocks (2019-2021)

Source: ECA, based on cases reported to the cooperation mechanism - Commission Annual Reports; Average inward investment stock - Eurostat - EU direct investment positions by country, ultimate and immediate counterpart and economic activity (BPM6), Inward FDI¬Ý2019-2021.

Notification of ineligible cases and lack of information on risk profiles in notifications undermine the efficiency and effectiveness of the framework

36 Article¬Ý9 of the Regulation outlines the type of information for any cases of FDI undergoing screening. Given its limited scope, the Commission and the member states agreed on a voluntary basis, in the FDI Screening Expert Group, to provide more extensive information in a ‚Äúnotification form‚Äù. These forms are submitted through a secure network by duly appointed authorities in the member states, and generally provide the information required. Whenever important information was missing, the Commission made additional requests, to which member states replied by providing further information. The system would be more efficient if notification forms included all essential information by default.

37 When assessing whether an FDI is likely to impact public order or security, the Commission and the member states may take into account the factors listed in Article¬Ý4 of the Regulation. These factors relate to the nature of the investment (e.g.¬Ýwhen it involves critical infrastructure or technologies) and to the nature of the investor (e.g. past involvement in criminal activities, or controlled by third-country governments or armed forces). However, these factors are neither exhaustive nor mandatory.

38 We found that the cooperation mechanism is overburdened with ineligible, (i.e.¬Ýout of scope) and with low-risk cases (i.e. not warranting an opinion) Figure¬Ý5 shows that 30¬Ý% of the 886 cases member states notified by the end of 2022 were either ineligible, or their eligibility was unclear. According to the Commission, 68¬Ý% were eligible, but of low risk. Only in 2¬Ý% of cases did the Commission identify likely risks or shared relevant information by issuing opinions.

Figure¬Ý5 ‚Äì Share of total cases reported by eligibility and risk profile from 2020 to 2022

Source: ECA, based on Commission data.

39 We found that member states are informed of screening activities in other member states through the cooperation mechanism, as our survey and interviews with member states also showed. The information obtained as a result of their requests or submitted comments helps to make better informed decisions before specific FDI transactions are authorised. However, in our view, the notification forms and the information they contain have the following weaknesses:

- notifications do not provide detailed explanations of the threats FDI poses to security or public order (risks listed in Article¬Ý4 of the Regulation, or others that may apply). Although the forms require a description of relevant risk factors, these are very often filled in only with a short title of the sector or type of activity. In our view, risks to security and public order are not generally flagged in the notification, even if high risks were known in advance;

- notifications do not require the member state authorities to reach a conclusion about the eligibility of a case; and

- notification forms lack automatic validation for completeness of information and eligibility, based on a standard set of information fields.

40 These weaknesses resulted in additional work for the Commission, including having to gather further information from member states, thereby significantly reducing the efficiency of the framework.

The Commission’s opinions provide added value, but its assessments and recommendations are sometimes not sufficiently developed

41 As set out in the Regulation, the Commission is responsible for carrying out its own risk assessments and providing opinions when it believes that FDI poses a high risk to more than one member state or to EU projects and programmes. For this purpose, the Commission developed internal guidance that we took into account for our assessment. To carry out its risk assessments, the Commission needs to make sufficient resources available in order to assess the sensitivity of EU targets in relation to any of the factors mentioned in Article¬Ý4 of the Regulation that may represent a serious threat to security and public order from FDI, to identify the ultimate beneficiary owners and their risk profiles, and to take account of sanctions imposed by the EU and member states in relation to investment. As per the Commission‚Äôs internal procedures, DG¬ÝTRADE should consult all other relevant DGs to ensure robust due diligence.

42 FDI may lead to a capital movement under Article¬Ý63¬ÝTFEU. This Article prohibits any restriction on capital movements between member states and between member states and third countries. Pursuant to Article¬Ý65¬ÝTFEU, restrictions on the free movement of capital may be justified when necessary and proportionate for the achievement of the objectives defined in the Treaty, including on public security and public policy grounds, as defined by the CJEU. FDI may also lead to the establishment of a third-country investor in the EU, e.g. when such an investment acquires a controlling stake in an EU-based undertaking.

43 As the explanatory memorandum accompanying its proposal for the Regulation states, with respect to movement of capital, such public interests must be interpreted strictly. They may be relied upon only if there is a genuine and sufficiently serious threat to a fundamental interest of society. Restrictions on fundamental freedoms must not be misapplied in order to serve purely economic ends. Furthermore, investment screening mechanisms should comply with the general principles of EU law, in particular the principles of proportionality and legal certainty. These principles require the procedure and criteria for an investment screening to be defined in a non-discriminatory and sufficiently precise manner, and should be reflected in the Commission’s risk assessment and recommendations.

The Commission’s risk assessment provides value, but the Commission has limited access to data on individual investor profiles

44 Article¬Ý4 of the Regulation provides a non-exhaustive list of risk factors relating either to the critical nature of the target company, its products or activity in the EU, or to the risk profile of the foreign investors. Our review of cases showed that the Commission described potential risks comprehensively including identifying spillover risks or critical dependencies. Our survey and our interviews with member state authorities corroborated their appreciation of the Commission‚Äôs role in assessing risks.

45 The Commission is uniquely positioned not only to assess whether FDI is likely to affect security or public order in more than one member state, or whether FDI may affect projects and programmes of EU interest, but also to estimate their impact at EU¬Ýlevel, thus adding additional value to the cooperation mechanism. We found that DG¬ÝTRADE collaborates with other Directorates-General and asks member states to provide more information where required. It also identifies those targets that participate in certain EU projects and programmes, as listed in the Annex to the Regulation.

46 Europol and Eurojust databases may shed light on certain risks relating to past engagement in illegal or criminal activity by individual investors. However, the Regulation does not contain any provisions enabling such cooperation and information-sharing that would help in better assessing security risks of individual investors.

Gaps in the assessment of the likelihood and impact of risk elements for high-risk cases

47 Our examination of the Commission’s opinions found the following issues in the quality of its assessments. To satisfy auditee confidentiality requirements, we have grouped our findings by type of issue (specific examples cannot be given due to the highly sensitive nature of the cases reviewed):

- description of the identified risks and their likelihood – we found that certain risks identified were not sufficiently evidence based and lacked clear explanations of how likely such risks were to occur, with the consequence that the impact on security and public order may be overestimated;

- the link between the risk and the investment– we found that security-of-supply risks in Europe, often linked to single or limited suppliers, may pose a risk to certain critical supplies or dependencies. However, the source of the risk stems from past industrial trends, past policy decisions, or market realities for which the investors are not directly responsible;

- quantifying the potential impact of an acquisition – the Commission’s risk assessments do not quantify, to the furthest extent possible, the potential impact or disruption that may result from a specific investment;

- consideration of other national and EU policies – most assessments do not explain which other national or EU instruments or policies should address the risks identified, and – where they do exist – why they are not sufficient to fully address the risks without any further case-specific measures. This relates to at least the following areas: export controls including dual-use items; data-protection laws; controls under financial-sector regulations; and EU sanctions intended to prohibit investments;

- the distinction between the different roles and responsibilities of shareholders and management is not always taken into account, but may have a bearing on recommended mitigation measures, if any. There are various safeguards in place and legal distinctions made between an entity’s administrator or managing board, and its shareholders, which are taken into consideration to varying degrees in the examined opinions;

- highlighting potential financial EU support to address certain risks the Commission does not assess whether there is scope for support or mitigation through direct EU resources (e.g. from the EU budget, the European Investment Fund (EIF), the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF), or any other available EU¬Ýfunding) or at member state level.

The Commission’s recommendations are partially effective at addressing the risks identified

48 We assessed the quality of the recommendations made by the Commission in its opinions. The key factors which led the Commission to issue an opinion include risks and measures relating to sensitive EU targets (such as security of supply of critical goods and technology, or dual-use products), and risks related to investors (such as foreign-state influence or control). We found that when the Commission identified what it regarded as a likely impact on security or public order, it recommended mitigating measures to the member state hosting the FDI.

49 In terms of the quality and relevance of the mitigating measures proposed, we found that in some cases the Commission:

- proposes mitigating measures without explaining the extent to which they would address the risks identified;

- recommends various safeguards which do not sufficiently distinguish between the roles and responsibilities of shareholders and management, or which may raise issues of enforceability and thus cannot effectively mitigate the risks identified. The commitments they impose are binding on the investor, but not necessarily on the target company and its management;

- recommends restrictions or conditions on investors or target companies, which are not consistent with a market-economy environment. Measures which require EU targets and investors to increase inventories or production capacity place a financial and legal obligation on a private party to resolve a systemic market situation for which the investor is not directly responsible.

50 Our evidence showed that where certain transactions involved individuals on a sanctions list, the member states concerned did not block the investment. Our view is that if investors are on a sanctions list which prohibits them from investing, no further assessment by the Commission is necessary to issue an opinion, because any such investment would be illegal if the member state permitted it.

Appropriate operational tools and resources are in place, but reporting is not sufficiently focused

51 The Commission should adhere to sound financial management principles and to its Internal Control Framework. Thus, it should make the necessary resources available so that cases can be managed in a timely manner. It should also ensure that it has adequate information-management tools to carry out its own assessments, as well as secure communication tools to manage information exchanges with member states. The annual reports and the five-year evaluation of the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation should explain the extent to which the Regulation has been implemented across the EU, and address any important systemic issues that emerge. Based on relevant and reliable data, the Commission’s reports should focus on key risks and how to address them.

The Commission has put appropriate tools and resources in place to support the implementation of the cooperation mechanism

52 We found that the Commission has adequate resources in place to handle the current case load in a timely manner, and that it provided assessments to tight deadlines. However, streamlining opportunities exist to improve the management of future caseload increases, including ensuring that Commission staff always use existing templates and checklists.

53 The Commission has set up an appropriate database to manage and document its work, with sufficient indicators relevant for assessing the effectiveness of the Regulation. It also set up appropriate IT tools to exchange information securely for the purposes of the cooperation mechanism.

54 The Commission established well-designed internal guidelines and processes. One procedure which we found very useful was the development of a dedicated checklist that requires Commission staff to identify, justify and provide evidence for determining a likely risk. Despite the importance of this checklist for facilitating consistent and comprehensive assessments, the other DGs involved in providing input to DG¬ÝTRADE do not systematically use it.

55 In accordance with Article¬Ý12 of the Regulation, the Commission has convened a group of experts from all member state authorities, with the aim of providing it with advice and expertise, sharing examples of good practice and lessons learned, and exchanging views on trends and issues of common concern relating to foreign direct investments. We note that the Commission has set up the necessary platform for the experts‚Äô forum, and that all member states ‚Äì with or without a national screening mechanism ‚Äì are participating.

56 Article¬Ý13 of the Regulation opens up the possibility for international cooperation between member states and the Commission on the one hand, and third-country authorities on the other. The Commission has participated in and organised various initiatives, such as talks with third countries, cooperation with the OECD and the US, and stakeholder conferences and events attended by third-country authorities.

The Commission’s annual reports place insufficient focus on the risks identified and common approaches for preventing them

57 As required by the Regulation, the Commission has published its first and second annual implementation reports. The Regulation does not specify the information to be included in the annual reports, but they do provide more information than member states included in comparable reports. However, even taking account of the need to balance transparency and security considerations due to the sensitive nature of data, we believe that the reports contain insufficient information and data for reporting purposes and, more importantly, for assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of FDI screening and EU-level cooperation. The reasons for this are as follows:

- the Regulation does not require any specific information to be included in the Commission’s annual report;

- the reports provide a comprehensive summary of legislative developments in member states and FDI screening activities being carried out at both EU and national level. However, we have found that the reports do not focus sufficiently on the types of risks being identified for the related sectors, or the types of risks relating to investors or deal structures (in particular, those included under Article¬Ý4);

- the reports provide information on FDI into the EU. However, the information on the volume of inward investment has limited added value, as it does not necessarily correlate with security and public-order risks (e.g. geographical concentration, or the location of sensitive or strategic assets);

- the FDI figures as reported misrepresent actual foreign capital flows into the EU because they quote the value of global deals rather than the relevant EU direct investment. This does not provide an accurate picture of the size of the relevant portion of FDI transactions within the EU. The challenge the Commission faces is the lack of reliable statistics or detailed information from member states, breaking down such global transactions by their different EU and non-EU elements;

- the lack of aggregate information on risk patterns and the frequency of mitigation measures make it more difficult to identify issues of common concern and to develop potential EU-level solutions or improvements over time.

Conclusions and recommendations

58 Overall, the Commission has taken appropriate steps to establish and implement a framework for screening foreign direct investment in the EU. However, significant limitations persist across the EU, reducing the effectiveness and efficiency of the framework at identifying, assessing and mitigating security and public-order risks.

59 The cooperation mechanism facilitated the sharing of screening information and risk assessments on FDI. However, some features in the design of the Regulation mean that the cooperation mechanism is less effective at protecting the EU‚Äôs public order and security. Firstly, as the Regulation does not require member states to set up an FDI screening mechanism, there were still six member states that did not have an FDI screening mechanism in place as of September¬Ý2023. Secondly, as the Regulation is silent on the scope of national screening mechanisms when they exist, there are significant differences in scope and approach between screening systems in the member states. Thirdly, member states are under no obligation to inform the Commission or other member states of their final decisions in cases where the Commission or other member states respectively issue opinions or send comments identifying likely risks to security or public order. Lastly, the Commission‚Äôs recommendations are not binding on member states carrying out screening, even when overall EU interests are at stake (see paragraphs¬Ý26-28).

60 The Regulation leaves room for interpretation with regard to the notion of ‚Äúlikely impact‚Äù on security or public order. Moreover, as a result of the Regulation‚Äôs design, comparable rules are not consistently applied to comparable situations (particularly in the treatment of intra-EU trade from entities that are foreign-owned and controlled, or of portfolio investments). Furthermore, member states can determine the scope of security and public order for themselves. All of these elements, together with the fact that member states do not have to report the outcome of their screening decisions to the Commission, make it very challenging for the Commission to monitor the implementation of the framework and to ensure that investors are not discriminated against, or that the free movement of capital is not unduly restricted (see paragraph¬Ý29). It also creates multiple blind spots, compromising the legitimate need for the EU to safeguard its security and public order interests. Improvements are also necessary in the Commission‚Äôs risk assessments and recommendations.

Recommendation¬Ý1¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝSeek the necessary amendments in the Regulation to strengthen the EU FDI screening framework

Without prejudice to the decisions of the co-legislators, we recommend that the Commission should in its revision of the framework:

- include the requirement that all member states establish screening mechanisms.

- clarify key concepts such as:

- the definition of ‘likely’ risk by aligning it clearly to the notion of “genuine and sufficiently serious threat to a fundamental interest of society”;

- portfolio investments;

- cover explicitly:

- investments made in the EU by a foreign owned undertaking economically active in the EU

- investments, whereby a foreign investor acquires a foreign target with subsidiaries in the EU;

- include the obligation for member states to provide the Commission and other member states, as the case may be, with feedback on the outcome of their screening decisions, in particular where the Commission has issued an opinion and/or the respective member states have provided a comment.

Target implementation date: 2024

61 We found significant differences between the FDI screening mechanisms of member states, and the Commission has not completed any formal assessment of their compliance with the minimum conditions stipulated in the Regulation. As things stand, several member states pre-screen transactions and only notify the cooperation mechanism of those transactions that are likely to affect their own public order or security, thereby depriving the other member states and the Commission of a chance to assess whether a transaction can have an impact on them. All of this results in a large share of FDI that is not subject to screening, and a substantial number of low-risk or ineligible cases which overburden the system (see paragraphs¬Ý32-39).

Recommendation¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝAssess whether national screening mechanisms comply with regulatory standards, and streamline concepts across EU screening mechanisms

The Commission should:

- provide an assessment of whether national screening mechanisms comply with the standards set out in Article¬Ý3 of the Regulation;

- clarify the practice of pre-screening; and

- encourage member states to align their criteria, timeframes and processes so that cases spanning multiple member states can be coordinated effectively (multi-jurisdiction cases).

Target implementation date: (a) 2026; (b) and (c) 2025.

62 The Commission‚Äôs risk assessment provides EU added value not only by identifying risks to security and public order relating to factors under Article¬Ý4 of the Regulation, but also by contributing to forward-looking thinking on potential vulnerabilities and critical dependencies as they arise at EU level. However, this approach has limitations in covering all types of risk, such as assessing past criminal or security-related risks presented by individual investors at EU level (see paragraphs¬Ý44-46).

63 The Commission provided assessments to tight deadlines. However, we found issues with the quality of the Commission‚Äôs assessments that we reviewed (see¬Ýparagraph¬Ý47) regarding:

- the description of the identified risks and their likelihood;

- links between the risk and the investment;

- quantification of the potential impact of an acquisition;

- consideration of other national and EU policies;

- the distinction between different roles and responsibilities of shareholders and management; and

- the highlighting of potential financial EU support to address certain risks.

64 The Commission‚Äôs opinions to member states may recommend mitigating measures or prohibition of FDI. In our view, recommendations are only partially effective at addressing the risks identified, as justification for the mitigation measures being recommended can be improved, notably by specifying how the proposed measures would reduce exposure to the risks if implemented. Furthermore, when recommending mitigating measures, the Commission proposes conditions which may raise issues of enforceability or be inconsistent with a market-economy environment (see paragraph¬Ý49).

Recommendation¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝImprove the cooperation mechanism and the Commission‚Äôs assessments in order to provide better justification of mitigating actions relating to high-risk cases

The Commission should:

- assess eligibility before it starts risk assessments;

- make risk assessments more comprehensive by exploring the scope for cooperation with Europol and Eurojust to assess criminal or security risks presented by individual investors;

- in its assessments, focus on risks which are reasonably likely to occur, and avoid hypothetical scenarios;

- strengthen its opinions by indicating clearly if the opinion is just for sharing the information or for addressing serious threats to security and public order, and proposing proportional measures taking into account roles and responsibilities of investors, existing EU or national legislation, policies and instruments; and

- recommend prohibiting cases where foreign investors are on a sanctions list banning investment, irrespective of the risk profile of the target.

Target implementation date: June¬Ý2024

65 The Commission has put appropriate operational tools, IT systems and resources in place to handle the current case load arising from the cooperation mechanism. It has reported in a timely manner in its annual reports, and has fulfilled its ‚Äúreporting‚Äù role in implementing the Regulation. Nevertheless, given the need to balance transparency and security considerations due to the sensitive nature of the data, we believe that the information and data that the Commission and member states have provided are not sufficient to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of FDI screening and EU-level cooperation. The fact is that they do not sufficiently focus on the types of risk being identified for the related sectors, or the types of risk relating to investors or deal structures (see paragraphs¬Ý52-57).

66 Moreover, the Regulation does not provide for adequate feedback by the member state recipient of the Commission‚Äôs opinion, or for member state comments that would allow the Commission or the member state making those comments to monitor and report on the effectiveness of the system (see paragraph¬Ý29¬Ý(c)).

Recommendation¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝImprove the quality of reporting

The Commission should improve the quality of its annual reports by focusing on critical risks and approaches to mitigating them. In cooperation with member states, it should also improve the scope and quality of the underlying data.

Target implementation date: 2024

This report was adopted by Chamber IV, headed by Mr Mihails Kozlovs, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 24¬ÝOctober¬Ý2023.

For the Court of Auditors

Tony Murphy

President

Annexes

Annex¬ÝI ‚Äì¬ÝComparison between EU and US screening frameworks

Elements of FDI screening framework | EU FDI screening framework and cooperation mechanism | The Committee on Foreign Investment |

|---|---|---|

Governance | DG¬ÝTRADE manages the cooperation mechanism in conjunction with all member states, and manages overall policy discussions within the expert group composed of experts nominated by all member states. | CFIUS is an inter-agency committee authorised to review the national security implications of foreign direct investment in the United States. |

Powers | The FDI screening framework is an empowering framework, not a harmonising one. It does not bind member states on whether to screen, or what to screen. The final decision to block or authorise FDI lies with the member states. The Commission may issue opinions when it identifies that a given FDI has a likely impact on the public order or security of more than one member state, or of projects or programmes of EU¬Ýinterest. These opinions may include non-binding mitigation, or a recommendation to prohibit investments. Screening member states have the power to adopt binding mitigation measures and, if needed, prohibition decisions. Member states cannot block FDI in another member state. | CFIUS is authorised to block transactions that fall within its jurisdiction. It may also impose measures to mitigate any threats to US national security. Authorisation to block or the imposition of mitigation measures are binding. |

Scope | Any case being screened by a member state must be reported to and shared with other member states and the Commission through the cooperation mechanism. For FDI not undergoing screening, the Commission has ex officio powers to request information from a member state. Includes direct investment by foreign nationals. Indirect investment is not included in the scope of the Regulation beyond cases of circumvention, but some member states screen intra-EU investments in practice. | Any transaction that could result in control of a US business by a foreign national. Control is defined broadly as direct or indirect power ‚Äì whether or not it is exercised¬Ý‚Äì to determine, direct or decide on important matters affecting a business, and can include minority investments. |

Mandatory Filings | Mandatory filings are determined at national level by different member state screening mechanisms. The EU Regulation does not make any specific sector or transaction type mandatory. The EU Regulation only requires that all FDI being screened should be reported to and shared with other member states. | Critical Technologies: Foreign investments involving a US business with critical technologies, for which a US regulatory authorisation would be required for its use by a foreign national. Foreign-Government Ownership: Certain transactions in which a foreign-government owned entity acquires a substantial interest in a US business. |

Legal Penalties | No legal penalties envisaged at EU level. Different penalties applicable across member states. | Three types of violation: failure to file; non-compliance with CFIUS mitigation; material misstatement, omission, or false certification Potential civil penalties for failure to comply, or violations of a material provision of a mitigation requirement. |

Abbreviations

CFIUS: Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States

CJEU: Court of Justice of the European Union

DG¬ÝTRADE: The¬ÝEuropean Commission‚Äôs Directorate-General¬Ýfor¬ÝTrade¬Ý

EEA: European Economic Area

EFTA: European Free Trade Association

EIF: European Investment Fund

Eurojust: European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation

Europol: European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation

FDI: Foreign Direct Investment

NATO: North Atlantic Treaty Organization

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development¬Ý

RRF: Recovery and Resilience Fund

TFEU: Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

TTC: Trade and Technology Council

Glossary

Foreign direct investment (FDI) – an investment of any kind by a foreign investor that aims to establish or to maintain lasting and direct links between the foreign investor and the target company to carry on an economic activity in a member state, including other arrangements that enable effective control or participation in the management of a company carrying out an economic activity. This definition excludes portfolio investments.

Foreign investor – a natural person of a third country or an undertaking of a third country making a foreign direct investment.

Screening – a procedure allowing to assess, investigate, authorise, condition, prohibit or unwind foreign direct investments.

Screening mechanism – an instrument of general application, such as a law or regulation, and accompanying administrative requirements, implementing rules or guidelines, setting out the terms, conditions and procedures to assess, investigate, authorise, condition, prohibit or unwind FDI on grounds of security or public order.

Audit team

The ECA’s special reports set out the results of its audits of EU policies and programmes, or of management-related topics from specific budgetary areas. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to be of maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by Audit Chamber¬ÝIV Regulation of markets and competitive economy, headed by ECA Member Mihails¬ÝKozlovs. The audit was led by ECA Member Mihails¬ÝKozlovs, supported by Edite¬ÝDzalbe, Head of Private Office and Laura¬ÝGraudina, Private Office Attach√©; Juan¬ÝIgnacio¬ÝGonzalez Bastero, Principal Manager; Georgios¬ÝKarakatsanis, Head of Task; Jacques¬ÝSciberras, Joerg¬ÝGenner and Joaquin¬ÝHernandez¬ÝFernandez, Auditors; Mari-Liis Pelmas-Gardin, secretarial support.

From left to right: Joerg¬ÝGenner, Georgios¬ÝKarakatsanis, Edite Dzalbe, Mihails¬ÝKozlovs, Laura¬ÝGraudina; Juan¬ÝIgnacio¬ÝGonzalez¬ÝBastero; Mari-Liis Pelmas-Gardin, Jacques¬ÝSciberras.

COPYRIGHT

© European Union, 2023

The reuse policy of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is set out in ECA Decision No¬Ý6-2019 on the open data policy and the reuse of documents.

Unless otherwise indicated (e.g. in individual copyright notices), ECA content owned by the EU is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC¬ÝBY¬Ý4.0) licence. As a general rule, therefore, reuse is authorised provided appropriate credit is given and any changes are indicated. Those reusing ECA content must not distort the original meaning or message. The ECA shall not be liable for any consequences of reuse.

Additional permission must be obtained if specific content depicts identifiable private individuals, e.g. in pictures of ECA staff, or includes third-party works.

Where such permission is obtained, it shall cancel and replace the above-mentioned general permission and shall clearly state any restrictions on use.

To use or reproduce content that is not owned by the EU, it may be necessary to seek permission directly from the copyright holders:

Figure¬Ý1: ¬©¬ÝOECD, 2022: Framework for Screening Foreign Direct Investment into the EU ‚Äì Assessing effectiveness and efficiency. This translation was not created by the OECD and should not be considered an official OECD translation. The OECD shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

Software or documents covered by industrial property rights, such as patents, trademarks, registered designs, logos and names, are excluded from the ECA’s reuse policy.

The European Union’s family of institutional websites, within the europa.eu domain, provides links to third-party sites. Since the ECA has no control over these, you are encouraged to review their privacy and copyright policies.

Use of the ECA logo

The ECA logo must not be used without the ECA’s prior consent.

| ISBN 978-92-849-1299-5 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi: 10.2865/885487 | QJ-AB-23-028-EN-N | |

| HTML | ISBN 978-92-849-1285-8 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi: 10.2865/356789 | QJ-AB-23-028-EN-Q |

Endnotes

1 Article¬Ý206¬ÝTFEU.

2 Article¬Ý2(1) of Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452.

3 Second Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, SWD(2022)¬Ý219 final, COM(2022)¬Ý433 final, p.¬Ý2.

4 European¬ÝParliament resolution of 23¬ÝMay¬Ý2012 on EU and China: Unbalanced Trade.

5 Commission reflection paper on ‚ÄúHarnessing Globalisation‚Äù issued on 10¬ÝMay¬Ý2017.

6 Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452 of the European¬ÝParliament and of the Council of 19¬ÝMarch¬Ý2019, establishing a framework for the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, OJ¬ÝL¬Ý79¬Ýl, 21.3.2019, pp.¬Ý1-14.

7 See Articles¬Ý6(3) and 7(2) of the Regulation.

8 See Article¬Ý13 of the Regulation.

9 OECD¬Ýreport, Figures¬Ý4 and 5.

10 Articles¬Ý6 to 8 of Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452.

11 The Commission has so far published two annual reports COM(2021)¬Ý714 final of 23¬ÝNovember 2021 and COM(2022)¬Ý433 final of 1¬ÝSeptember 2022.

12 The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947), and the General Agreement on Trade in Services.

13 Trade¬ÝPolicy¬Ýreview - An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy, COM(2021)¬Ý66¬Ýfinal¬Ý‚Äì 18¬ÝFebruary¬Ý2021.

14 Commission‚Äôs explanatory memorandum COM(2017)¬Ý487 final, 2017/0224(COD), , SWD(2017)¬Ý297 final, p. 4. See also: Case¬ÝC-463/00 Commission vs Spain, paragraph¬Ý34; Case¬ÝC-212/09 Commission v Portugal, paragraph¬Ý83; Case¬ÝC-244/11 Commission v Greece, paragraph¬Ý67; C-446/04 - Test Claimants in the FII Group Litigation, paragraph¬Ý171, Case Judgment of 14¬ÝMarch 2000, Case C-54/99 √âglise de scientologie v The Prime Minister, paragraph 17.

15 Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2019/452, Recital¬Ý9.

16 See Judgment¬Ýof 28¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2006, Commission v. Kingdom of the Netherlands Joined cases C-282/04 and C-283/04, ECLI:EU: C:2006:608, paragraph¬Ý19.

18 OECD¬Ýreport, paragraphs¬Ý104-118, 161 and Table¬Ý5.

19 OECD¬Ýreport on ‚ÄúAcquisition and ownership-related policies to safeguard essential security interests‚Äù, May¬Ý2020, pp.¬Ý44-63.

20 OECD¬Ýreport on ‚ÄúFramework for screening Foreign Direct Investment into the EU ‚Äì Assessing effectiveness and efficiency‚Äù, 2022, paragraphs¬Ý139-156.