Executive summary

I Lobbying is widely recognised as an essential tool in democratic societies. It allows organisations and individuals to have some input into policy and decision-making by bringing forward their concerns and ideas. On the other hand, without transparency mechanisms, lobbying can result in undue influence, unfair competition, or even corruption. The European Parliament and the European Commission first set up the EU Transparency Register through an interinstitutional agreement in¬Ý2011. The Council joined the register in the latest agreement, which dates from 2021 and will be subject to a review by July¬Ý2025. Our audit therefore aims to provide timely analysis and recommendations that could be considered for that review.

II The objective of our audit was to assess whether the transparency register is a useful means of providing transparency on the lobbying activities in EU policy and decision-making. The audit focused on the period¬Ý2019-2022.

III We conclude that the 2021¬Ýinterinstitutional agreement on the transparency register contains the main elements required by international principles for a lobbying framework and the transparency register provides useful information to allow citizens to follow lobbying practices. However, in practice, weaknesses and gaps in that information reduce the transparency of lobbying activities taking place in the three signatory institutions.

IV One of the key features introduced in¬Ý2021 was the ‚Äòprinciple of conditionality‚Äô, which stated that registration is a precondition for certain lobbying activities at the signatory institutions. We found, however, that the institutions had different approaches to this principle, and that it covered only certain activities and only top-ranking staff. Moreover, while lobbyists can be removed from the register in certain cases, enforcement measures to ensure that lobbyists comply with registration and information requirements are limited.

V The transparency register Secretariat is a joint operational structure set up to manage the functioning of the register. The Secretariat’s working arrangements are not formalised, and its joint nature means significant coordination is required, which in turn increases the risk to operational efficiency. Our audit identified problems with data quality, such as duplicated registrations, inconsistent or incomplete financial data, and missing mandatory data. We noted recent improvements in the Secretariat’s checks.

VI Registrants can self-declare to which category they belong, which determines their financial disclosure requirements. There is a therefore a risk that registrants funded by third parties do not disclose financial information including their funding sources by declaring that they represent their own interests or the collective interests of their members.

VII We also found significant limitations in the information provided by the transparency register public website. Some important data, such as individual meetings with Members of the European Parliament, or historical data on re-registered entities are missing. Furthermore, the website does not provide aggregated data on lobbyists and their activities in an interactive way.

VIII We recommend that the signatory institutions:

- strengthen the transparency register framework;

- publish information on non-scheduled meetings with lobbyists;

- improve data quality checks; and

- improve the user-friendliness and relevance of the transparency register’s public website.

Introduction

01 Lobbying is widely recognised as an integral part of democracy. Interest representatives, often referred to as ‘lobbyists’, can provide valuable insights and data for public decision-makers with their expertise and evidence about policy issues. The treaty on European Union requires the EU institutions to “maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”1. However, if lobbying is not sufficiently transparent, it can lead to undue influence, unfair competition, or even corruption.

02 There is no single definition of lobbying (see Annex¬ÝI), although the ones available ‚Äì for example, from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), or the Council of Europe2 ‚Äì are rather similar. The Council of Europe defines lobbying as a ‚Äúconcerted effort to influence policy formulation and decision-making with a view to obtaining some designated result from government authorities and elected representatives‚Äù3. Regulating lobbying touches upon issues of ethics, transparency, integrity, and the fight against corruption. Several governments around the world, and various international organisations have developed regulations, principles, standards or guidelines4 with the aim of establishing transparent and ethical lobbying practices.

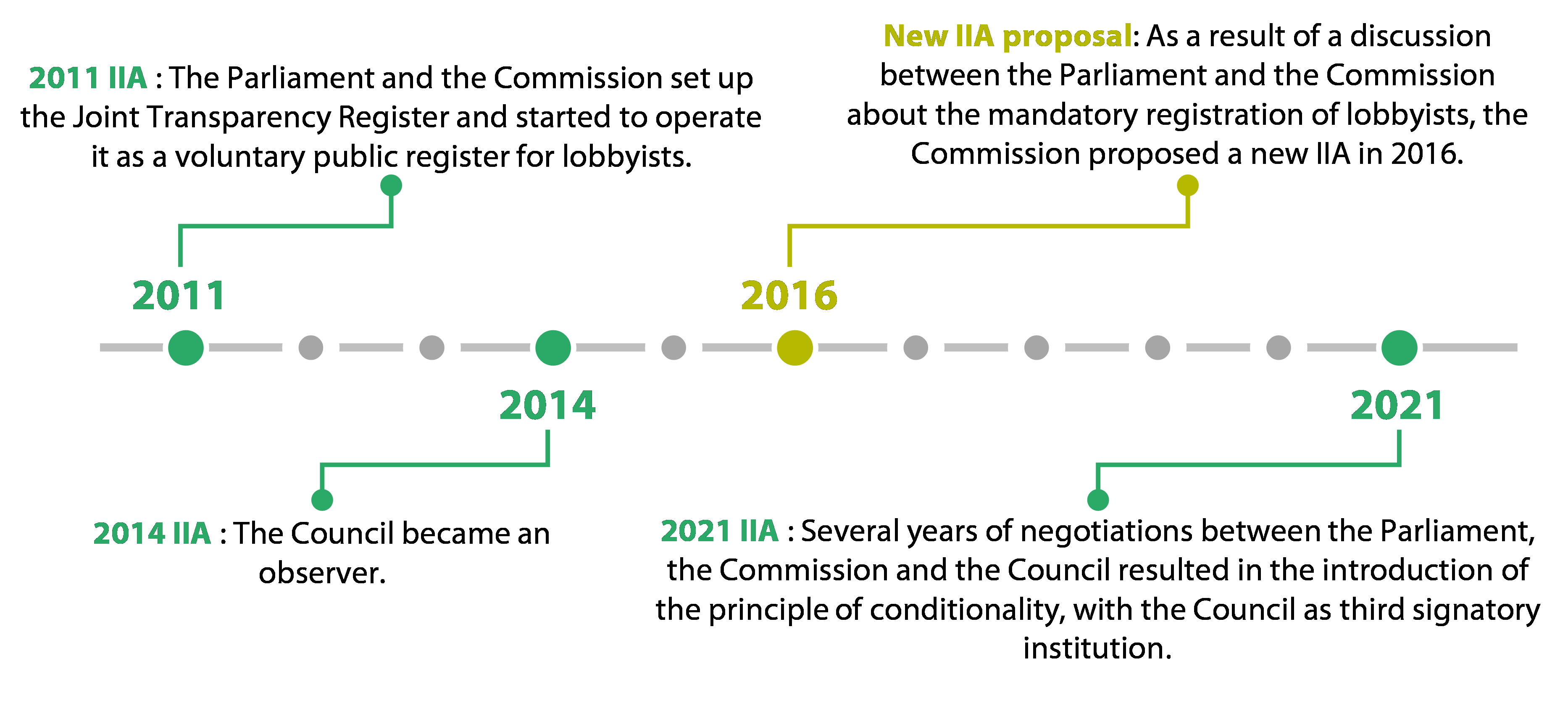

03 In¬Ý2011, the European Parliament and the European Commission decided to set up a Joint Transparency Register, later renamed the EU Transparency Register (EUTR), by means of an interinstitutional agreement (2011¬ÝIIA). The agreement was revised in¬Ý2014, when the Council of the European Union became an observer. In¬Ý2021, a new agreement was signed when the Council joined as a third signatory institution, see Figure¬Ý1.

Figure¬Ý1¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝTimeline of agreements on a transparency register

Source: ECA, based on 2011¬ÝIIA, 2014¬ÝIIA, 2016¬ÝCommission proposal for an Interinstitutional Agreement and 2021¬ÝIIA.

04 As with its predecessors, the 2021¬ÝIIA defined certain rules by which its signatory institutions agreed to be bound. It is not an enforceable EU legislative act. Its aim is to allow citizens to follow lobbying practices and find out about the potential influence of lobbyists, including through the disclosure of their financial support5.

05 The 2021¬ÝIIA introduced the principle of conditionality6. This makes registration in the EUTR a necessary precondition for lobbyists who wish to have certain interactions with members or staff of the signatory institutions. Each institution undertook in the 2021¬ÝIIA to establish its own set of conditionality and transparency measures through its own individual decisions7. These define the activities for which EUTR registration is a precondition for lobbyists‚Äô interaction with signatory institutions (e.g. attending meetings, conferences, expert groups or hearings), and other activities for which registration is encouraged, although not a precondition. The signatory institutions agreed on a coordinated approach regarding the lobbying activities covered by the 2021¬ÝIIA, but not on which of these activities they each decided to make conditional on registration8.

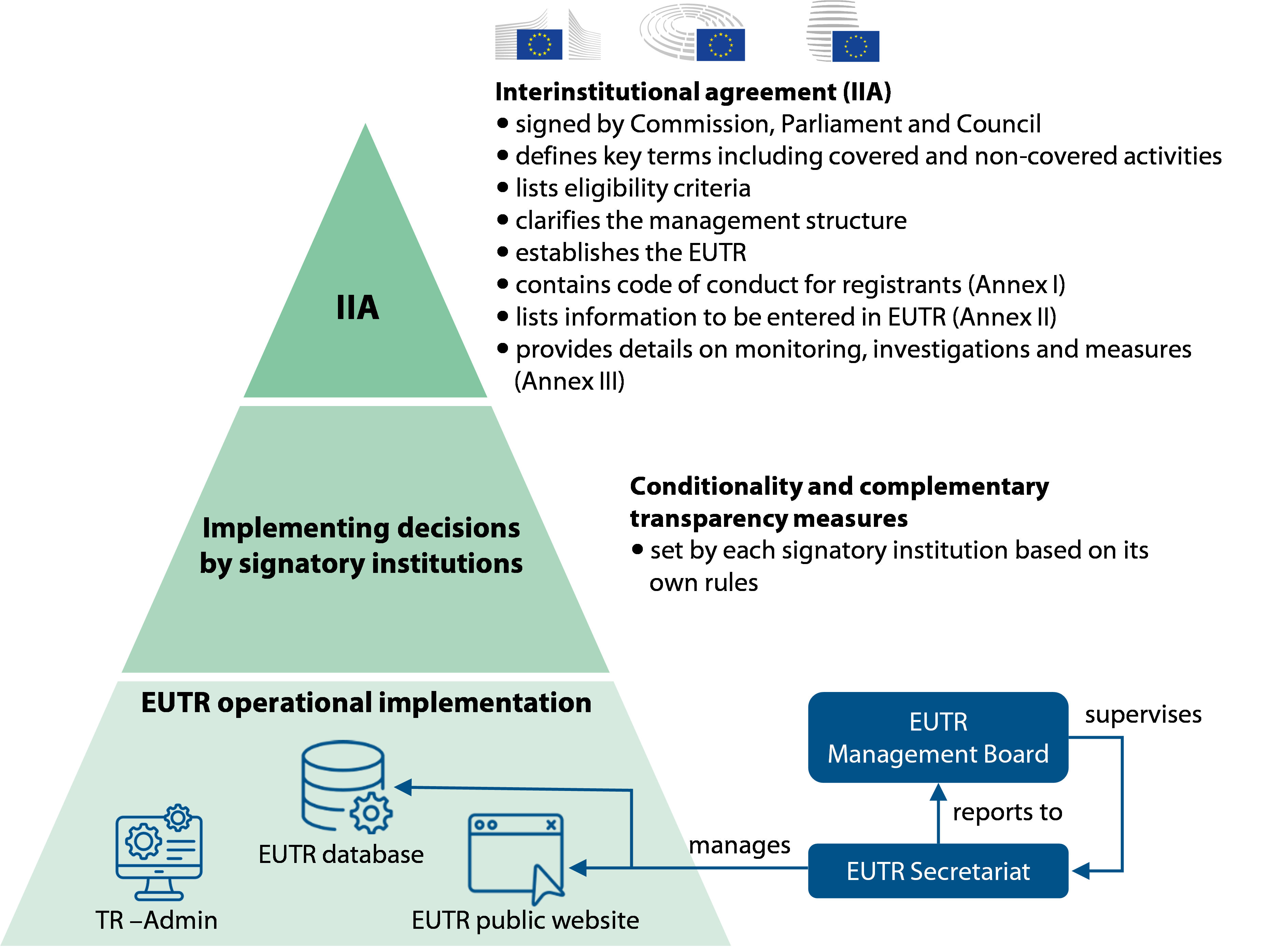

06 The Secretaries-General of the signatory institutions form the Management Board of the EUTR. The Board oversees the overall implementation of the 2021¬ÝIIA, determines the priorities for the EUTR, issues general instructions to the EUTR Secretariat, and adopts the annual report prepared by the Secretariat. The Secretaries-General chair the Board on a rotating basis for a term of 1¬Ýyear and decide by consensus9. The Secretariat, which assists the Board, is a joint operational structure consisting of staff from the three signatory institutions, set up to manage the functioning of the EUTR database and the EUTR‚Äôs public website with an equivalent of 10¬Ýfull-time staff (during 202210).

07 The signatory institutions delegate to the Board and Secretariat the power to act on their behalf for the adoption of individual decisions concerning applicants and registrants (e.g. on eligibility, removal from the register, checks on data quality)11. Figure¬Ý2 provides an overview of the implementation arrangements for the EUTR.

Figure¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝThe 2021 IIA and implementation arrangements

Source: ECA, based on 2021¬ÝIIA.

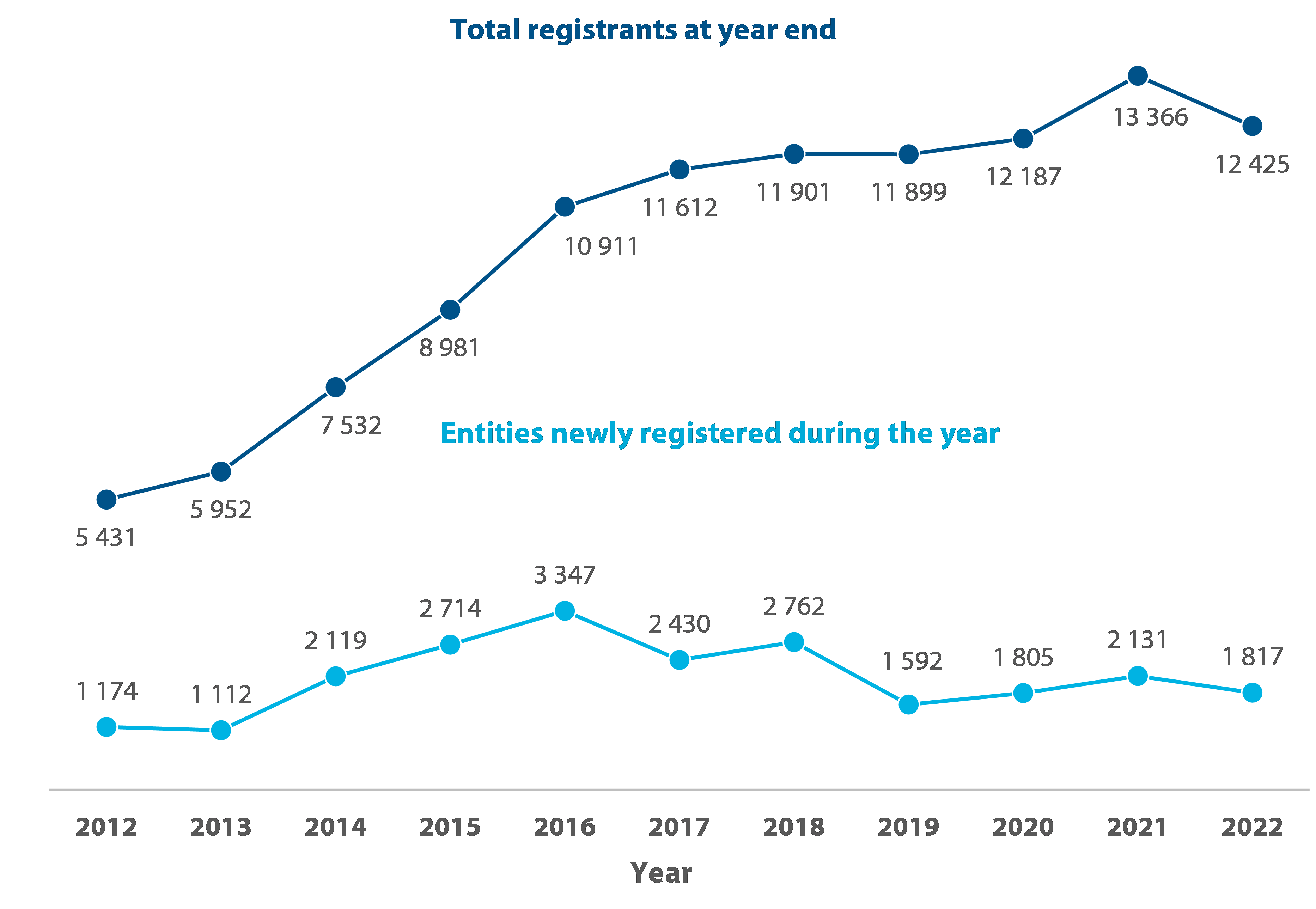

08 The number of entities registered in the EUTR has grown markedly since its inception and, at the end of¬Ý2022, it included more than 12¬Ý000 registrants, see Figure¬Ý3.

Figure¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝEntities registered in the EUTR over the years

Source: ECA, based on EUTR annual reports.

09 Articles¬Ý11 and¬Ý12 of the 2021¬ÝIIA enable non-signatory EU institutions, bodies, offices and agencies plus member states to notify the Management Board about measures they take to make certain activities conditional on registration in the EUTR, or about any complementary transparency measures. By September¬Ý2023, only the European Economic and Social Committee had notified the Board about such complementary transparency measures12, which entered into force in June¬Ý2023. The Committee of the Regions adopted similar measures on 4¬ÝJuly¬Ý2023.

10 Member states only notified a political declaration made at the occasion of the adoption of the 2021¬ÝIIA by the Council13, in which they undertook to make meetings between lobbyists and their permanent representative and deputy permanent representative conditional on the registration of such lobbyists in the EUTR. This concerned meetings only during member states‚Äô 6-month Council presidency term and the preceding six months, and the member states also undertook to publish information on those meetings.

11 In recent years, there have been also considerable developments in EU member states regarding the regulation of lobbying. Currently, eight member states (Germany, Ireland, Greece, France, Lithuania, Austria, Poland, and Slovenia) have mandatory registration systems for lobbyists, and four (Belgium, Italy, Netherlands and Romania) have voluntary ones14. Outside the EU, Canada and the USA are among the countries that have established mandatory lobbying registers.

12 In December¬Ý2022, allegations emerged that Qatar had unlawfully influenced former and current Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to achieve foreign policy goals15 (‚ÄúQatargate‚Äù). Subsequently, the Parliament adopted a number of decisions in connection with the way the Parliament implements the EUTR:

- in December¬Ý2022, the Parliament‚Äôs President put forward a 14-point proposal to tighten rules for MEPs, two of which concerned stronger checks on lobbyists and mandatory publication of meetings;

- in¬ÝApril¬Ý2023, the body that lays down internal rules for the Parliament (the Bureau) adopted new measures regarding former MEPs, stipulating that they should wait until six months after the end of their European Parliament mandate before engaging in lobbying activities, and that they should register in the EUTR before doing so;

- in May¬Ý2023, the Bureau adopted new ‚ÄúRules on access to the European Parliament‚Äù to clarify access rights of lobbyists, which entered into force on 8¬ÝJune¬Ý2023;

- in June¬Ý2023, the Bureau adopted additional rules on the participation of interest representatives at all events held at the Parliament, which entered into force on 12¬ÝJuly¬Ý2023; and

- in September¬Ý2023, the Parliament amended its Rules of Procedure to include a general requirement for all MEPs and their parliamentary assistants to publish scheduled meetings relating to parliamentary business with lobbyists falling within the scope of the EUTR, which entered into force on 1¬ÝNovember¬Ý202316.

Audit scope and approach

13 The objective of this audit was to assess whether the EUTR is a useful means of providing transparency about lobbying activities at the EU level. We assessed whether:

- the 2021¬ÝIIA, as the basis of the EUTR, is consistent with internationally recognised principles of transparency and integrity in lobbying, including the existence of enforcement features for lobbyists;

- the signatory institutions make meaningful use of EUTR registration as a precondition for lobbying activities;

- the EUTR Secretariat’s working arrangements are conducive to good data quality on lobbying activities; and

- the EUTR’s public website provides relevant content and is user friendly.

14 We did not assess whether a transparency register could be established and operated in ways other than through an interinstitutional agreement. We also did not assess alternative ways to operate the EUTR, such as setting it up within one of the signatory institutions rather than sharing the work between them, or giving the task to an independent external body.

15 Although there are no formally recognised international standards on lobbying, there are internationally recognised principles on this matter. We used the OECD’s ten principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying for our audit work and we consulted representatives from the OECD. We also took account of the Council of Europe’s recommendation “on the legal regulation of lobbying activities in the context of public decision making”17, which is in line with the OECD principles.

16 We reviewed publications18 on those internationally recognised principles and on good practices in national registration systems. We also reviewed the systems of the 12¬Ýcountries with either a mandatory or voluntary register for lobbyists, see paragraph¬Ý11, and referred to four countries which provide illustrations of good practice (Germany, Ireland, Austria, and Canada).

17 We carried out the audit work focusing on the period 2019-2022. We reviewed annual reports on the functioning of the EUTR, Management Board minutes and documents about the activities of the Secretariat. We interviewed the staff of the Secretariat, and staff of the Parliament, Council and Commission. We also met the OECD and the Ombudsman. We took into account relevant developments up to the end of September¬Ý2023.

18 We used data analysis techniques to cross-check the entire population of EUTR data (a total of 12¬Ý653 registrants at the time of our data extraction of 5¬ÝOctober¬Ý2022) against the payments recorded in the Commission‚Äôs accounting system (ABAC). We did substantive testing on EUTR data for completeness and accuracy. We also selected a risk-based sample of 100¬Ýregistrants to assess the data quality of registrants and the checks carried out by the Secretariat, based on certain risks such as blank data in mandatory fields, outlier data of cross-checks on staff numbers versus lobby costs, and discrepancies when cross-checking data with ABAC. Our sample included a broad range of lobbyists registered between¬Ý2008 and¬Ý2022 so that there was a high probability that they had undergone at least one quality check, including a retroactive assessment of eligibility criteria.

19 The 2021¬ÝIIA is subject to a review by July¬Ý2025. Our audit therefore aimed to provide timely analysis and recommendations that could be taken into account for that review.

Observations

The EUTR interinstitutional agreement has positive features, but enforcement measures fall short

20 The OECD‚Äôs ten principles19 provide decision-makers with directions and guidance to foster transparency and integrity in lobbying in four key areas (see also Table¬Ý1):

- building an effective and fair framework for openness and access;

- enhancing transparency;

- fostering a culture of integrity; and

- providing mechanisms for effective implementation, compliance, and review of the lobbying framework.

21 We assessed the consistency of the 2021¬ÝIIA with these principles.

2021 IIA is broadly consistent with international principles

22 The 2021¬ÝIIA establishes a framework and operating principles for the signatory institutions by laying down definitions20, defining the lobbying activities covered and not covered by the agreement21, and specifying governance and working structures22. The EUTR is set up with eligibility provisions for applicants, a code of conduct for lobbyists, specific information that should be entered into the EUTR, and provisions on monitoring, investigations and related measures23.We found that the 2021¬ÝIIA is broadly consistent with the ten OECD principles, as shown in Table¬Ý1.

Table¬Ý1 ‚Äì Assessment of the 2021¬ÝIIA framework according to OECD principles

OECD¬Ý10 principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying | Our assessment of the 2021¬ÝIIA | |

|---|---|---|

I. Building an effective and fair framework for openness and access | 1. Countries should provide a level playing field by granting all stakeholders fair and equitable access to the development and implementation of public policies. | ‚úî Establishes the EUTR through which lobbyists can have access to the development and implementation of EU policies. O Registration is not required for all lobbying activities. It is up to the institutions to decide which of the activities covered by the 2021¬ÝIIA require registration as a pre-condition. |

2. Rules and guidelines on lobbying should address the governance concerns related to lobbying practices and respect the socio-political and administrative contexts. | ‚úî The signatory institutions form the governance of the EUTR via the Management Board, providing a mechanism for accountability and supervision. The EUTR includes eligibility provisions, a code of conduct and operational procedures. | |

3. Rules and guidelines on lobbying should be consistent with the wider policy and regulatory frameworks. | ‚úî Establishes rules and guidelines on lobbying adapted to EU purposes. | |

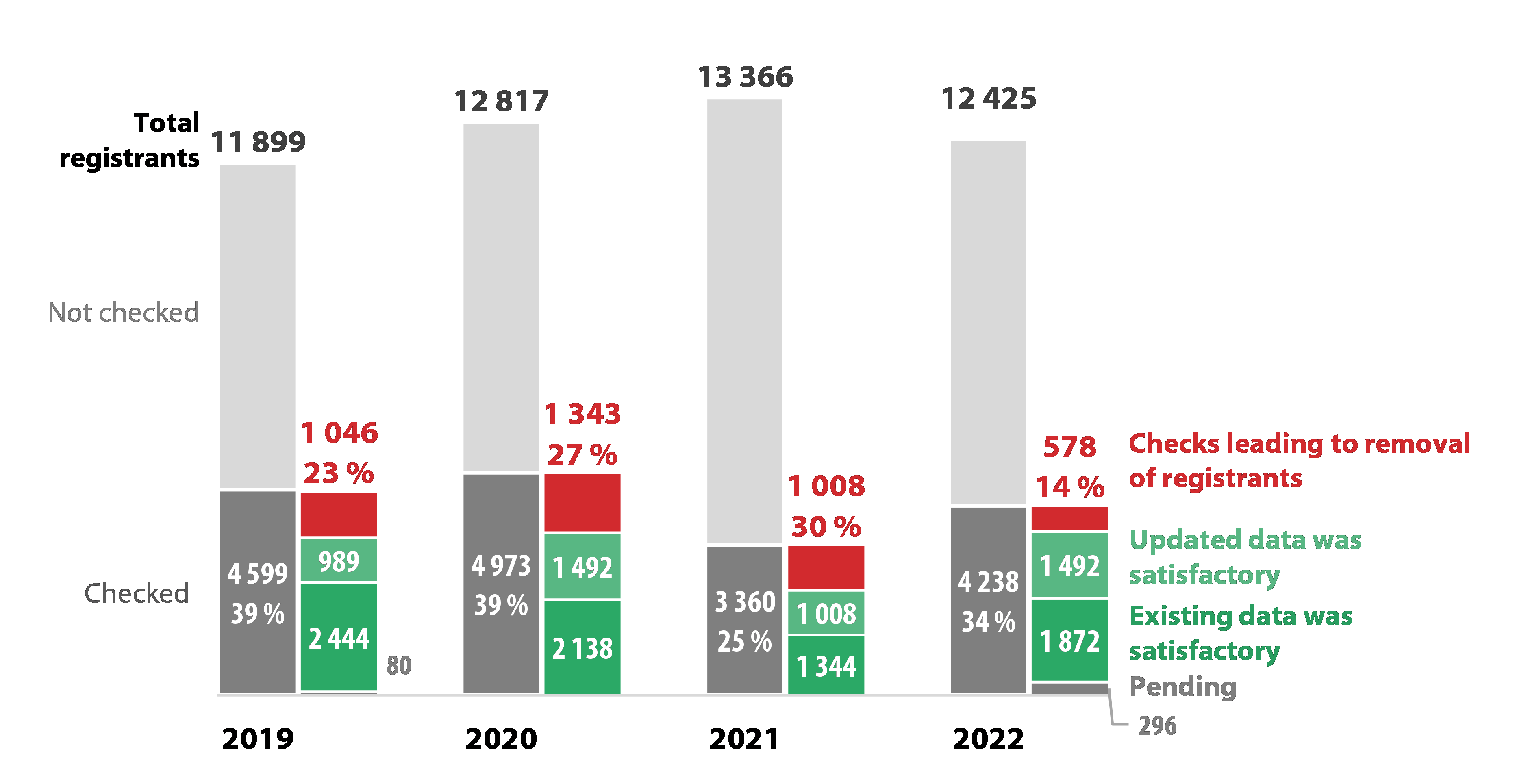

4. Countries should clearly define the terms 'lobbying' and 'lobbyist' when they consider or develop rules and guidelines on lobbying. | ✔ Provides a definition of ‘lobbyist’ / ‘interest representative’. ✔ It defines the term 'lobbying' indirectly and provides an indicative list of lobbying activities. | |

II. Enhancing transparency | 5. Countries should provide an adequate degree of transparency to ensure that public officials, citizens, and businesses can obtain sufficient information on lobbying activities. | ‚úî Establishes a website which is publicly accessible and enables stakeholders to consult information on lobbying. |

6. Countries should enable stakeholders – including civil society organisations, businesses, the media, and the general public – to scrutinise lobbying activities. | ||

III. Fostering a culture of integrity | 7. Countries should foster a culture of integrity in public organisations and decision making by providing clear rules and guidelines of conduct for public officials. | ‚úî This is addressed via the individual decisions of the signatory institutions, EU Staff Regulations and the wider ethical framework of the EU institutions. |

8. Lobbyists should comply with standards of professionalism and transparency; they share responsibility for fostering a culture of transparency and integrity in lobbying. | ‚úî Requires confirmation of adherence to the EUTR code of conduct before applicants are eligible for registration. | |

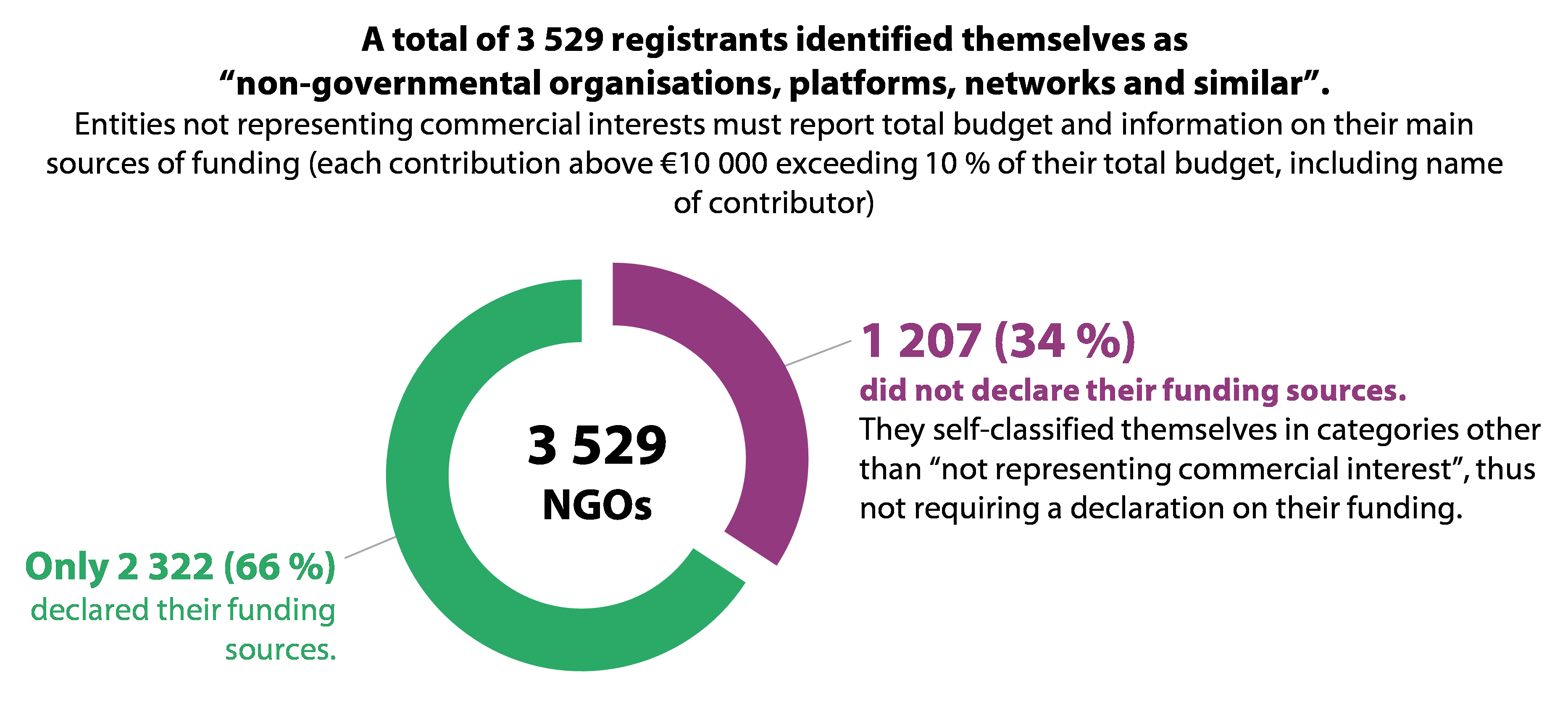

IV. Providing mechanisms for effective implementation, compliance and review | 9. Countries should involve key actors in implementing a coherent spectrum of strategies and practices to achieve compliance. | ‚úî Establishes a monitoring mechanism but does not lay down specific obligations for lobbyists regarding all lobbying activities. O Measures exist to address non-compliance, but no sanctions. |

10. Countries should review the functioning of their rules and guidelines related to lobbying on a periodic basis and make necessary adjustments in light of experience. | ‚úî Requires regular assessment of the implementation of measures taken with a view to, where appropriate, making recommendations on improving and reinforcing such measures, without specifying what ‚Äòregular‚Äô means. Stipulates that there must be a review of the 2021¬ÝIIA by July¬Ý2025. | |

‚úîPositive feature(s) | ||

OShortcoming(s) | ||

Source: ECA, based on Recommendation of the Council on principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying, OECD/LEGAL/0379 and 2021¬ÝIIA.

23 The 2021¬ÝIIA does not set out minimum requirements for how it should be implemented in practice. It leaves scope for the signatory institutions to define the activities for which registration in the EUTR should be a pre-condition and how to implement these conditions. This has led to the signatory institutions applying the 2021¬ÝIIA in different ways, for example, concerning which members and staff of the institutions are covered, what constitutes a meeting, and what information about meetings should be published. Consequently, there are different approaches to how lobbyists can interact with the signatory institutions.

The main enforcement measure available is removal of lobbyists from the register

24 According to the OECD principles “to ensure compliance, countries should design and apply a coherent spectrum of strategies and mechanisms, including properly resourced monitoring and enforcement”24. The Council of Europe also recommends that legal regulations on lobbying should contain sanctions for non-compliance, which should be effective, proportionate, and dissuasive25.

25 The 2021¬ÝIIA is not a legislative act and therefore cannot establish sanctions for lobbyists. If lobbyists on the register breach the rules and principles of the 2021¬ÝIIA code of conduct, the main enforcement measure available is their removal from the EUTR26. Depending on the seriousness of the breach, the Secretariat can prohibit the lobbyist from registering again for a period of between 20¬Ýworking days and two years and can also publish the measure taken on the EUTR website. Between¬Ý2019 and¬Ý2022, 990 lobbyists on average were removed from the register each year following quality checks or failure to update their registration on time. However, out of these only six lobbyists were removed following complaints and investigations, and one of these was prohibited from re-registering. Information on this prohibited lobbyist was published.

26 In other systems that are based on legislation, in addition to removal from the relevant register, fines are the most common form of sanction. In some of these systems, criminal sanctions can also be applied, see Box¬Ý1. As the EUTR is a voluntary register, such criminal or financial sanctions are legally not possible.

Examples of sanction measures in national transparency registers based on legislative acts

Germany

If the registration is (i) not done, (ii) not done correctly, (iii) not done in good time, or (iv) not done in full, fines of up to ‚Ǩ20¬Ý000 may be imposed for a negligent violation and up to ‚Ǩ50¬Ý000 for an intentional violation.

Ireland

Failure to comply with lobbying regulations is punishable by a fine of up to ‚Ǩ2¬Ý500 or a term of imprisonment of up to two years.

Austria

Professional lobbying activities that contravene the applicable lobbying act are punishable by a fine of up to ‚Ǩ60¬Ý000.

Canada

At federal level, violations of lobbying regulations are punishable by terms of imprisonment ranging from 6¬Ýmonths to two years.

Source: ECA, based on Lobbyregistergesetz (Lobbying Register Act); Regulation of Lobbying Act¬Ý2015, Lobbying‚Äì und Interessenvertretungs‚ÄìTransparenz‚ÄìGesetz (Act on Transparency in Lobbying and Interest Representation) and Lobbying Act R.S.C.¬Ý1985, c.¬Ý44 (4th¬ÝSupp.).

Not all lobbying requires EUTR registration, but the institutions have put in place some complementary transparency measures

27 The signatory institutions implement the 2021¬ÝIIA by adopting their own individual implementing decisions on conditionality and complementary transparency measures. Elements of the ethical framework of the institutions also form part of the context. We assessed whether the implementation of the 2021¬ÝIIA by the signatory institutions covers the interactions with lobbyists comprehensively and provides lobbyists with fair and equal access to the development and implementation of public EU policies.

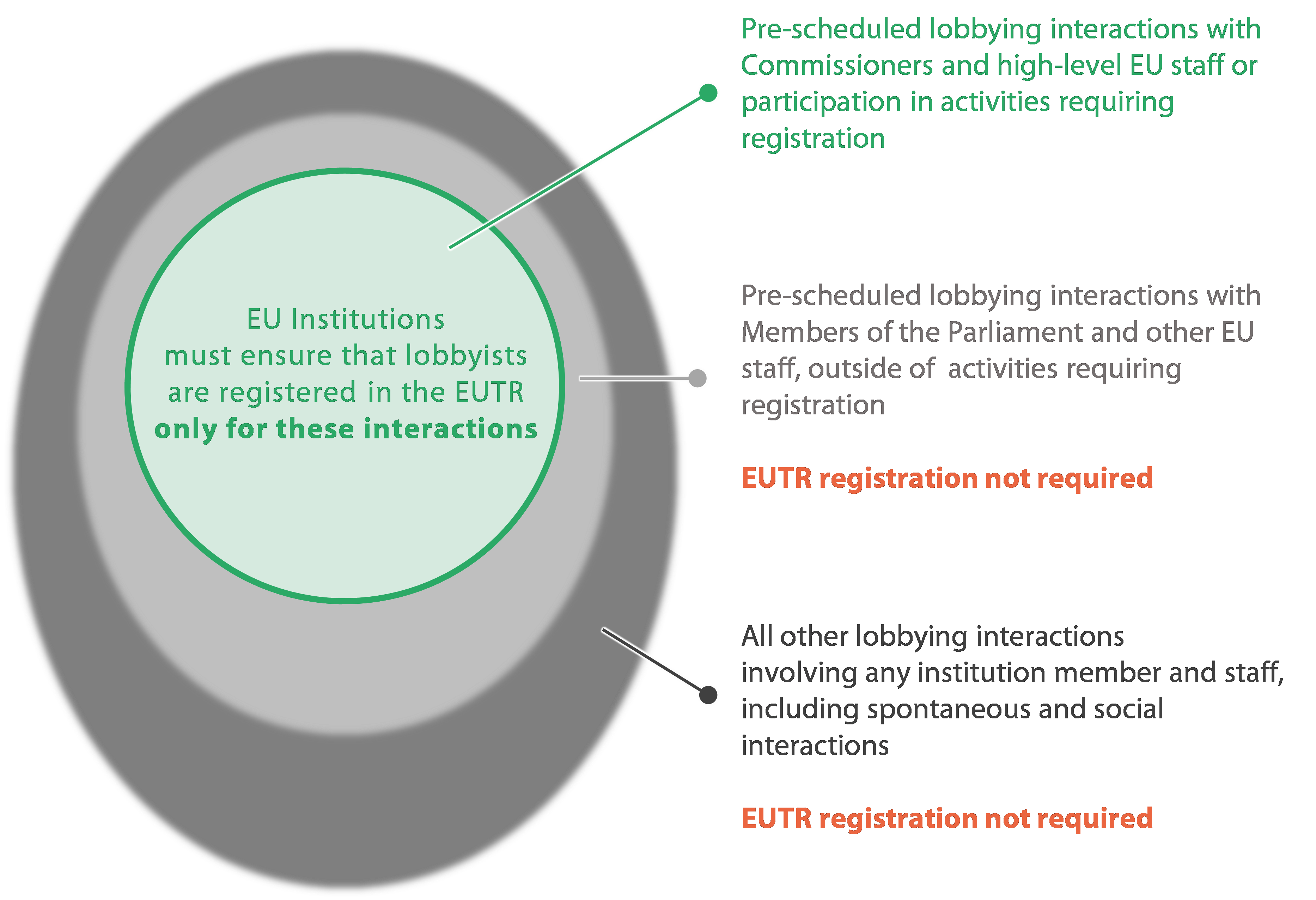

Lobbyists are required to register in the EUTR only for certain meetings and activities

28 According to the 2021¬ÝIIA, conditionality means the principle whereby registration in the EUTR is a necessary precondition for lobbyists to be able to carry out certain activities covered by the agreement27.The signatory institutions implement the principle of conditionality by requiring that:

- certain members (Commissioners only) and staff of the institutions meet only lobbyists registered in the EUTR;

- certain activities (e.g. attending hearings, conferences or expert groups) are limited to lobbyists registered in the EUTR.

29 The institutions make use of the above two categories in different ways. The Council and the Commission use both in parallel. The Parliament applies the principle of conditionality to meetings with lobbyists actively participating in events (for example, as a speaker or a co-host), but does not apply it to individual meetings with members and staff.

30 Lobbyists should be registered in the EUTR before certain meetings. It is the responsibility of the members and staff of the institutions to enforce this. We first assessed the extent to which members and staff are covered by the obligation to meet only registered lobbyists. We then assessed whether the range of activities that are limited to registered lobbyists only is sufficiently broad.

31 We found that the requirement for lobbyists to be registered before meeting institutional representatives applies only to high-level decision makers at the Council and Commission. For the Council, there are registration requirements for lobbyists only for meetings with high-level staff of its General Secretariat (Secretary-General and Directors-General). Members of staff other than the Secretary-General and Directors-General are encouraged to check whether lobbyists have an entry in the EUTR before agreeing to meet them28. At the Commission, the requirement for lobbyists to be registered in the EUTR before a meeting is applied for members, their cabinets and high-level staff (Secretary-General and Directors-General). At the Parliament, EUTR registration is required to obtain an access pass and, since July¬Ý2023, for co-hosting and active participation in events at its premises. Meeting registered lobbyists is a recommendation for MEPs and their assistants. There is currently no requirement for Parliament‚Äôs staff to meet only registered lobbyists.

32 This means that in none of the signatory institutions is it a precondition that lobbyists must be registered in the EUTR to meet staff below the level of Director-General. Meetings with most staff are therefore excluded from this requirement. For details, see Table¬Ý2 below.

Table¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝRequirements for members and staff meeting registered lobbyists

|

| European Parliament | General Secretariat of the Council | Commission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Members | MEPs/Commissioners | O | - | ‚úî |

Staff working for Members | Members’ staff (cabinets, MEPs’ assistants) | O | - | ✔ |

Staff | Secretary-General | ‚úò | ‚úî | ‚úî |

Directors-General | ‚úò | ‚úî | ‚úî | |

Deputy Directors-General | ‚úò | O | O | |

Directors | ‚úò | O | O | |

Senior advisors, advisors | ‚úò | O | O | |

Heads of unit | ‚úò | O | O | |

Other staff | ‚úò | O | O |

‚úîThe person(s) listed must meet only registered lobbyists

‚úòNo requirements

ONo requirements, but recommendation to meet only registered lobbyists

Source: ECA, based on recital¬Ý(6) of Commission Decision, 2014/838/EU, Euratom, Article¬Ý7 of Commission Decision 2018/C¬Ý65/06, Rules¬Ý11(2) and (3) of¬Ý European Parliament‚Äôs 2023 Rules of Procedure and Article¬Ý3 of Council Decision (EU) 2021/929.

33 The definition of what constitutes a meeting is relevant both for encounters for which registration in the EUTR is a precondition and for complementary transparency measures. The 2021¬ÝIIA addresses this by specifying what is not to be considered a meeting29. Each signatory institution applies this definition in practice either through formal implementing decisions or informal internal guidelines. See Box¬Ý2.

Signatory institutions’ definitions of an individual ‘meeting’

European Parliament

A scheduled meeting is to be understood as any meeting organised at the initiative of an interest representative, or of the MEP (for voluntary publication of meetings), chair, rapporteur, or shadow rapporteur (for compulsory publication of meetings), which has been accepted by the other party and for which a certain date and time is set. The adjective ‘scheduled’ implies that random meetings do not fall within the scope of the provision.

Council

The General Secretariat of the Council applies the lobbyist registration requirement to any meetings organised between interest representatives and the Secretary-General and Directors-General. This includes both physical meetings and those held using any form of remote connection, whether on Council premises or not; meetings of a purely private or social nature, or spontaneous meetings are not covered by the registration requirement.

Commission

“Meeting means a bilateral encounter organised at the initiative of an organisation or self-employed individual, Member of the Commission and/or a member of his/her Cabinet or a Director-General to discuss an issue related to policy-making and implementation in the Union. Encounters taking place in the context of an administrative procedure established by the Treaties or Union acts, which falls under the direct responsibility of the Member of the Commission or the Director-General, as well as encounters of a purely private or social character or spontaneous encounters are excluded from this notion”. For the Commission, videoconferences and all types of conference calls set up to discuss issues related to EU policy-making and implementation are considered meetings while one-to-one phone conversations are not.

Source: ECA, based on documents from the Parliament and the Council Article¬Ý2(b) of Commission Decision¬Ý2014/838/EU, Euratom and Article¬Ý2(a) of Commission Decision¬Ý2014/839/EU, Euratom.

34 The above shows that only meetings scheduled in advance clearly fall under the signatory institutions‚Äô definitions of a meeting. Spontaneous meetings are not covered by the 2021¬ÝIIA. Other interactions, such as unscheduled phone conversations and email exchanges are also not considered as meetings. This means that lobbying can take place beyond the scope of transparency provided by the EUTR for a range of interactions during which lobbyists might seek to influence members or staff.

35 As members and staff of the signatory institutions are responsible for implementing these measures in practice, it is important that they are aware of the relevant rules, guidelines and definitions. According to the annual reports on the functioning of the EUTR, the institutions have taken steps to raise awareness. Awareness-raising is even more important given that there were limited internal control mechanisms to ascertain whether, in practice, members and staff require lobbyists to register in the EUTR before meeting them.

36 Some national lobbying arrangements, based on legislative acts, are mandatory for lobbyists and cover a broader range of staff than at EU level. See an example in Box¬Ý3.

Lobbying arrangements in Germany

The German Lobbying Register Act applies to the representation of special interests at the Bundestag (German parliament) and the Bundesregierung (federal government). The register has been mandatory for lobbyists since 1¬ÝJanuary¬Ý2022.

For the German parliament, the scope of the register includes not only members of parliament and the most senior staff, but also staff working for them, on the assumption that messages aiming to influence policy formulation or decision-making will reach them as well.

37 The signatory institutions to the 2021¬ÝIIA require EUTR registration as a precondition for certain lobbying activities other than meetings. The implementing decisions of the Commission covering this topic date back to¬Ý2014 and¬Ý2018; the decisions of the Council and the Parliament are more recent. The Parliament requires registration for a number of activities. In June¬Ý2023, the Parliament updated its rules to cover more activities at its premises. Table¬Ý3 provides an overview of the activities in the institutions subject to EUTR lobbyist registration.

Table¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝLobbying activities requiring prior registration in the EUTR

Parliament | General Secretariat of the Council | Commission |

|---|---|---|

‚úî Intergroups and other unofficial groupings ‚úî Speakers in committee hearings ‚úî To obtain long-term access badges |

| ‚úî Participation by certain categories of individuals and organisations in Commission expert groups:

|

‚úî Co-host and/or participation as active guests in any events organised by the Parliament on its premises (since 12¬ÝJuly¬Ý2023) | ‚úî Thematic briefings and as speakers at public events organised by the General Secretariat l |

|

Source: ECA, based on Commission Decision C(2016)3301 on horizontal rules on expert groups, European Parliament‚Äôs 2019 Rules of Procedure, Rules¬Ý35 and 35¬Ýa) of¬ÝEuropean Parliament‚Äôs updated 2023 Rules of Procedure, the Bureau of the European Parliament‚Äôs decision of 12 June 2023, and Articles¬Ý4 and 5 of Council Decision (EU) 2021/929.

38 During our audit work, we found that one NGO, which was identified in ‚ÄúQatargate‚Äù, was not registered in the EUTR, but had co-hosted a conference with Parliament services on Parliament‚Äôs premises in June¬Ý2022. At the time, Parliament‚Äôs rules did not require EUTR registration as a precondition for such an activity. However, this was addressed with the update of the Parliament‚Äôs rules that entered into force in July¬Ý2023.

39 The Commission requires EUTR registration as a precondition only for participation by certain types of individuals and organisations in Commission expert groups. However, EUTR registration is not required by the Commission for any other lobbying activities described in Article¬Ý3 of the 2021¬ÝIIA. This implies that lobbyists may be involved in activities such as organising or participating in conferences, events, hearings, or communication campaigns with the Commission without being registered in the EUTR. Figure¬Ý4 summarises the scope of the implementation of the 2021¬ÝIIA principle of conditionality in practice.

Figure¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝSummary of the scope of the implementation of the 2021¬ÝIIA principle of conditionality in practice1

1The sizes of sections are illustrative only and do not represent actual proportions or relative magnitudes.

Source: ECA

40 The limited scope of EUTR registration requirements in practice, and the different approaches in the three institutions, mean that lobbyists which are not registered in the EUTR are not prevented from undertaking a range of meetings and other lobbying activities with members or staff of the institutions.

The institutions are taking complementary steps to increase transparency and encourage registration

41 The 2021¬ÝIIA states that each signatory institution can put in place complementary transparency measures alongside their conditionality measures ‚Äúto encourage registration and strengthen the joint framework‚Äù.

42 We assessed the range of complementary transparency measures implemented by the institutions in two main areas:

- publication of information about meetings and lobbying activities involving members and staff after they have taken place; and

- measures which provide incentives for lobbyists to register in the EUTR.

Publication of information about meetings and other lobbying activities

43 For each of the three signatory institutions, we identified the relevant rules and recommendations on publishing information about meetings and other activities, and we assessed their coverage and implementation. At the time of our audit, committee chairs, rapporteurs and shadow rapporteurs in the Parliament were required to publish information online about all scheduled meetings with lobbyists at the latest in advance of the relevant votes in committee and plenary30. With the Parliament‚Äôs update of its Rules of Procedure of 13¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2023, which entered into force on 1¬ÝNovember¬Ý2023, it is a requirement for all MEPs and their parliamentary assistants to publish information about all scheduled meetings with lobbyists falling within the scope of the EUTR31.

44 Information about these meetings is not included on the EUTR website. Instead, it is included in numerous individual online pages of MEPs, available on Parliament’s website. Meetings linked to specific parliamentary procedures are also listed on the entry for that procedure on the Legislative Observatory, under “Transparency”. Information about lobbyist participation in activities such as intergroups, committee hearings, or events organised by Parliament on its premises is also not published on the EUTR website.

45 At the Council, there are no requirements, including for high-ranking staff, to publish information about meetings with lobbyists. However, following the commitment of member states to make meetings between their permanent representatives and deputy permanent representatives to the EU and lobbyists conditional on registration in the EUTR (see paragraph¬Ý10), information about these meetings is published.

46 At the Commission, all Commissioners and Directors-General (including the Secretary-General) must make public, on their respective web pages, all the contacts and meetings held in their capacity with organisations or self-employed individuals32. This is followed in practice, and the information provided on the Commission’s webpages appears on the EUTR website. Where a lobbyist participates in Commission expert groups and public consultations, this information is also published on the EUTR website.

Measures to encourage registration

47 Two of the three signatory institutions implement useful complementary transparency measures to encourage lobbyists to register in the EUTR by providing, as soon as it is available, information to registrants about developments in subject areas in which they have expressed an interest. This is done using email notifications.

48 The Parliament notifies registrants about the activities of Parliament committees33. The Commission notifies registrants about its public consultations and roadmaps34. The Council currently has no such measures.

The EUTR Secretariat’s working arrangements encounter coordination and data quality challenges

49 The 2021¬ÝIIA formalised¬Ýa two-layer governance structure with a Secretariat reporting to a Management Board35, see paragraph¬Ý06. The Board oversees the overall implementation of the IIA and meets at least annually. It determines annual priorities and budget estimates, adopts annual reports prepared by the Secretariat and gives instructions to the Secretariat on specific activities.

50 The 2021¬ÝIIA established the Secretariat as a joint operational structure tasked with managing the operation of the register. It specified that the Secretariat would consist of the heads of unit, or equivalent, responsible for transparency issues in each signatory institution, and their respective staff36. Its duties include issuing guidelines for registration in the EUTR, providing a helpdesk service, and carrying out awareness-raising and other communication activities37. The Secretariat drafts the annual report for adoption by the Board. It is responsible for the day-to-day management of the EUTR, including developing and maintaining the EUTR website. We assessed whether the EUTR Secretariat‚Äôs working arrangements are suited to its responsibilities to achieve an optimal level of data quality in the EUTR on lobbying activities.

As a joint operational structure, the Secretariat requires significant coordination

51 Through the 2021¬ÝIIA, the signatory institutions committed themselves to organising the Secretariat as a joint operational structure. A head of unit from a signatory institution is designated as ‚ÄúCoordinator‚Äù for a renewable term of one year38, and Secretariat decisions are made by consensus among the three heads of unit.

52 While the Secretariat’s tasks are set out in the IIA, the institutions have not formalised between them how they organise the day-to-day work of the Secretariat. There is no dedicated team assigned to the Secretariat, nor established rules of procedure setting out how the three institutions will work together.

53 The Secretariat's tasks are distributed across the three institutions, taking into account a number of criteria, such as task content and relevance to the institution. The three institutions agreed to share the handling of new applications on a rotational basis (six days for the Council, 11-12¬Ýdays for the Parliament, 11-12¬Ýdays for the Commission). For other tasks, such as ongoing checks on EUTR data quality and the processing of complaints, the distribution of work depends also on availability of staff in the three institutions. The Commission hosts the EUTR website and provides IT support.

54 For¬Ý202239, the Secretariat estimated that the equivalent of 10¬Ýfull-time staff had worked on its tasks. This staff resource included some of the working time of the three heads of unit in the three institutions together with that of staff from their units.

55 The fact that these arrangements are not formalised means there is a need for coordination mechanisms. For example, as there is no delegation of powers from the heads of unit to the teams, all decisions need to be taken jointly by all three heads of unit from the three institutions. They have met on average once a month to discuss and agree on issues arising from their day-to-day management (individual complaints, distribution of data quality checks, etc). In between the meetings, the heads of unit can jointly take decisions by written procedure.

56 To meet the requirements of the 2021¬ÝIIA, the Secretariat published a new model registration form and guidelines for applicants and registrants. All EUTR applications are now checked against eligibility criteria. All lobbyists already registered were required to update their information using the new form by 30¬ÝApril¬Ý2022. Most of these registrants (11¬Ý200, or 87¬Ý%) had done so by that date. Checking all such amended registrations is part of the Secretariat‚Äôs tasks. This led to an increase in the Secretariat‚Äôs activity in¬Ý2022, in particular concerning helpdesk queries, see Table¬Ý4.

Table¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝNumber of Secretariat helpdesk queries, 2019-2022

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Helpdesk queries | 1¬Ý027 | 1¬Ý117 | 1¬Ý255 | 2¬Ý056 |

Source: ECA, based on EUTR¬Ý2019-2022 annual reports.

57 Before the 2021¬ÝIIA, correspondence with registrants was handled via separate functional email addresses at the Parliament and the Commission. Since the 2021¬ÝIIA, correspondence with applicants has been handled via the Secretariat‚Äôs back-office IT system (TR-ADMIN), while correspondence with registrants continues to be handled via the separate functional email addresses.

58 Given the increased workload necessary to maintain the register and the Secretariat’s non-formalised working arrangements, a considerable amount of coordination is needed to make sure that information is properly shared between the teams in the different institutions. This increases the risk to operational efficiency.

Data quality not optimal, but the Secretariat’s checks have recently improved

59 The Council of Europe notes that in systems requiring lobbyists to register, the lobbyists themselves have to make sure that their information is accurate and up to date. It thus recommends that a public authority in charge of the register should also be able to check the information for accuracy40.

60 The 2021¬ÝIIA code of conduct requires registrants to ‚Äúensure that the information that they provide upon registration (‚Ķ) is complete, up-to-date, accurate and not misleading‚Äù41. The Secretariat is responsible for monitoring the content of the EUTR, with the aim of achieving an optimal level of data quality.

61 The Secretariat set up a dedicated IT system, called TR-ADMIN, to facilitate all the main processes of the EUTR, namely applications, quality checks, complaint-handling and the database for the EUTR website. The system has been updated periodically since it was first established in¬Ý2011, and another update is planned for¬Ý2024.

62 Lobbyists have to apply online via the EUTR website to join the EUTR, and the Secretariat provides detailed guidelines for applicants and registrants. Applicants have to provide information in a number of categories, see Box¬Ý4.

Information that lobbyists must provide when applying for EUTR registration

- name and contact details;

- type of organisation;

- general mission, objectives, and remit;

- specific activities covered by the EUTR (e.g., main EU legislative proposals or policies targeted, participation in EU structures and platforms);

- number of people involved in activities;

- fields of interest, memberships, and affiliation;

- financial data (e.g. EU grants).

Information required has been expanded since 2021¬ÝIIA to include:

- interests represented;

- financial disclosure according to the chosen category of interests represented.

Source: Transparency register guidelines for applicants and registrants, 2021.

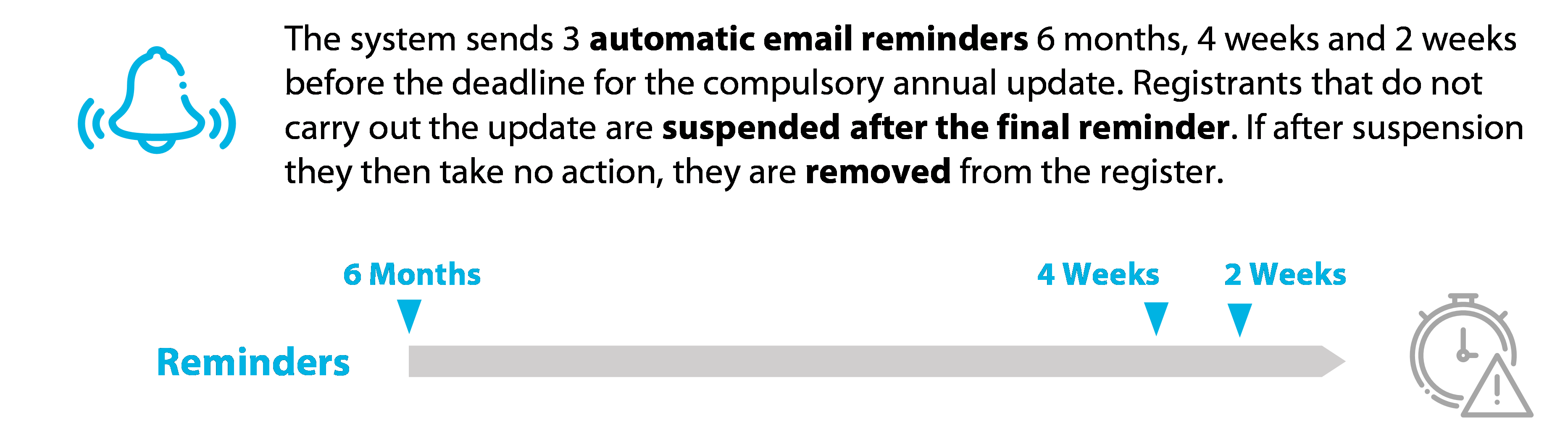

63 Since the 2018¬Ýguidelines, registrants are required to update their information annually. The TR-ADMIN IT system sends them automatic email reminders when the compulsory annual update is due. Registrants who do not carry out the update are first suspended and then, if necessary, removed from the register, see Figure¬Ý5.

Figure¬Ý5¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝReminder, suspension and removal functions of the EUTR IT management system

Source: ECA, based on the Secretariat’s documents.

64 Before the 2021¬ÝIIA, lobbyists were included in the EUTR as soon as they submitted their application, and were immediately visible on the EUTR website. At the time of application, the Secretariat did not establish their eligibility. The 2021¬ÝIIA strengthened this system by requiring that applicants‚Äò eligibility be established by the Secretariat before they could be included in the EUTR. On an ongoing basis, the Secretariat also checks all data of a subset of lobbyists which are already registered. Table¬Ý5 describes the data quality checks carried out prior to and since the 2021¬ÝIIA.

Table¬Ý5¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝSecretariat data quality checks over time

| Prior to the 2021¬ÝIIA | Since the 2021¬ÝIIA |

|---|---|---|

Limited checks at the time of application (“eligibility checks”) | None | Secretariat deems applicants to be eligible if they:

ohave declared that they observe the code of conduct (new in the 2021¬ÝIIA). If, during an eligibility check, data submitted on these four points is deemed not satisfactory then all an applicant‚Äôs other data is also checked. |

Checks covering all registrant‚Äôs data (‚Äúquality checks‚Äù) as shown in Box¬Ý4 | Every year, the Secretariat carries out:

| |

Source: ECA, based on Articles¬Ý3-4, Article¬Ý6(2), and Annex¬ÝI of the 2021¬ÝIIA, Secretariat‚Äôs Handbook, Ares (2019)6763329, and Secretariat internal handling procedures, undated.

65 Between¬Ý2019 and¬Ý2022, the Secretariat‚Äôs data quality checks covered, on average, 34¬Ý% of registrants each year. If, during a check, the Secretariat identified that lobbyists‚Äô data was not satisfactory, they were given an opportunity to update it. For 2019-2021, these checks led to the removal of, on average, 24¬Ý% of registrants checked, because either they were deemed ineligible, or they had failed to update their data. In¬Ý2022, after the 2021¬ÝIIA had come into force and new systematic checks of new applicants had been introduced, this figure dropped to 14¬Ý%, see Figure¬Ý6.

Figure¬Ý6¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝNumber of registrants checked per year, 2019-2022

Source: ECA, based on EUTR 2019-2022 annual reports.

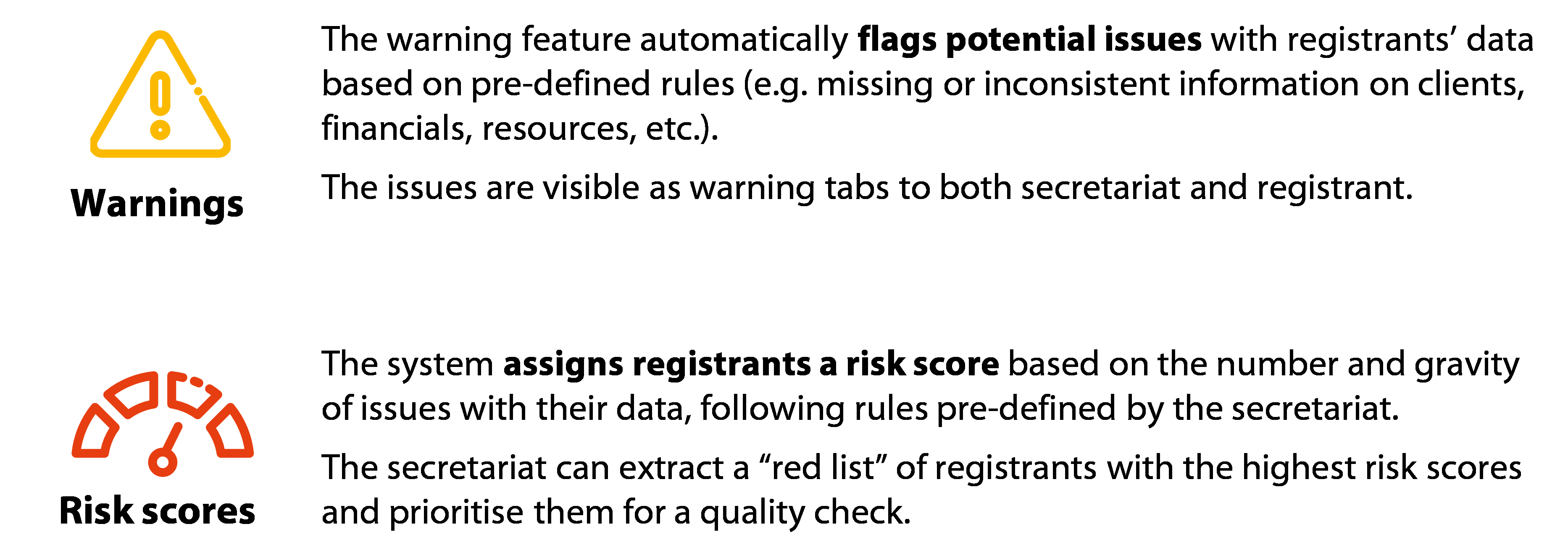

66 Rather than checking all registrants on a rotational basis to ensure coverage of all registrants every few years or doing risk-based checks, the Secretariat‚Äôs checks were based on complaints received, and done on an ad hoc basis, depending on staff resources available. Targeted checks were done based on the annual priorities set by the Board. When deciding which registrants‚Äô data to check, the Secretariat did not systematically use the TR-ADMIN¬ÝIT system feature that identifies registrants whose data is inconsistent, see Figure¬Ý7.

Figure¬Ý7¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝAutomated warning and risk scoring features of TR-ADMIN

Source: ECA.

67 We carried out the following work to assess the quality of the EUTR data:

- We analysed the reliability and coherence of the whole EUTR population of 12¬Ý653 lobbyists as of 5¬ÝOctober¬Ý2022. Our analysis focused on the following risks: duplicate registrations, missing mandatory information, EU grants declared by registrants inconsistent with financial information in ABAC, inaccurate information declared by registrants about amounts spent on lobbying via intermediaries, and inaccurate declaration of interests represented.

- We extracted a risk-based sample of 100¬Ýregistrants on which we carried out more targeted checks. Of these, 88¬Ýwere registered before the entry into force of the 2021¬ÝIIA and 12¬Ýafterwards. We checked the lobbyists‚Äô declaration of human resources and the extent to which it was consistent with their declared lobby budget. Where the Secretariat had done checks before 12¬ÝJanuary¬Ý2023 (which covered 97¬Ýout of the¬Ý100 in our sample), we assessed the Secretariat‚Äôs checks and the documentation thereof. For the whole sample of 100¬Ýregistrants, we checked compliance with all the registration requirements.

Issues identified with data quality and audit trail

68 In our testing covering the whole EUTR population, we identified the following issues, which indicate problems with data quality.

- The EUTR guidelines for applicants and registrants (1¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2021) state that a single registration principle is in force. However, we found five cases where a single lobbyist had more than one duplicate entry in the register, which the Secretariat subsequently corrected.

- Mandatory information missing: we found 27¬Ýcases where information about annual costs of lobbying activities was missing and 25¬Ýcases where there was no information about interest representation, although this had become mandatory with the 2021¬ÝIIA. All lobbyists registered before the 2021¬ÝIIA were required to submit information covering its new disclosure requirements by 30¬ÝApril¬Ý202242.

- Data about EU grants declared by lobbyists in the EUTR was inconsistent with data held in the Commission‚Äôs accounting system: for the last closed financial year (2021), we were able to compare 135¬Ýcases. The data matched in only six cases.

- Lobbyists acting as intermediaries did not always provide the required specific information about the identity of their clients and the amounts received from them: out of 661¬Ýintermediaries in the EUTR, 20 did not provide information in line with the guidelines for the most recent closed financial year and 27¬Ýfor the current financial year. We also found that 16¬Ýintermediaries which were founded more than three years prior to registration declared themselves as ‚Äúnewly founded entity‚Äù, and thus did not declare their figures for the most recent closed financial year when registering.

69 According to the OECD principles, disclosure requirements should enhance transparency by identifying those parties who have a direct interest in the outcome of the lobbying activities and their influencing budget43. Under the 2014¬ÝIIA, all registrants had to provide an estimate of their annual lobbying costs. Since 2021¬ÝIIA, different categories of interest representation have given rise to different types of financial disclosure, for details see Annex¬ÝII. The Secretariat provides some explanation and practical guidance to lobbyists on which categories they should choose for their self-declarations, giving some examples. However, lobbyists can choose any of the categories irrespective of their legal form. Annex¬ÝIII presents the complexity of the different financial disclosure requirements for each type of registrants.

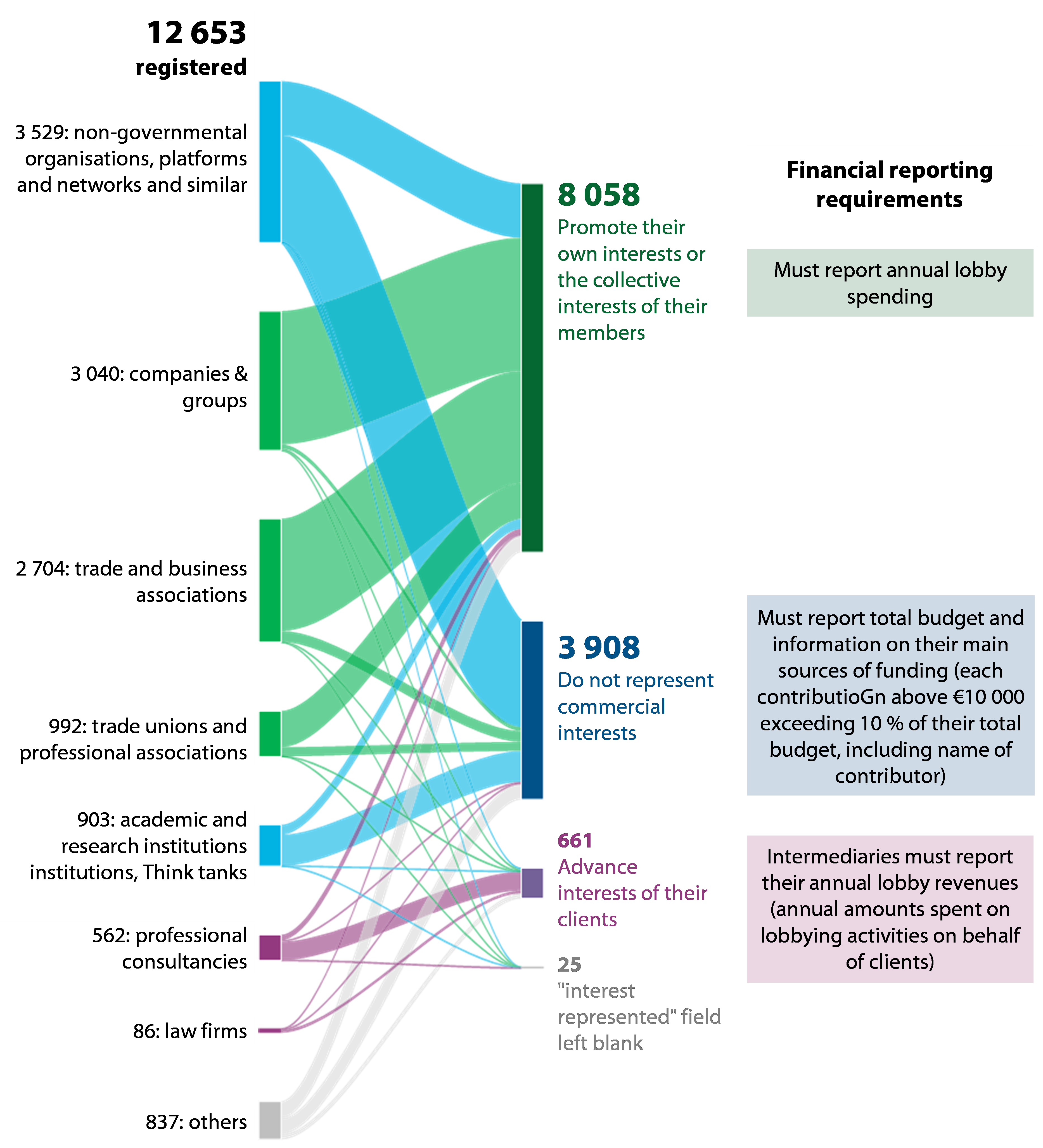

70 Through our analysis of the EUTR population, we found there was a risk that registrants funded by third parties (e.g., NGOs), can avoid disclosing financial information about this by declaring that they represent only their own interests or the collective interests of their members. Around a third of those who declared themselves ‚ÄúNGOs, platforms, networks and similar‚Äù (1¬Ý207 out of¬Ý3¬Ý529) made such declarations that they represented their own interests or the collective interests of their members, and therefore did not disclose financial support and funding received, see Figure¬Ý8. For registrants registered before the 2021¬ÝIIA, we did not find evidence that the Secretariat systematically checked self-declarations of NGOs on the interests they represent, which determines the financial information they disclose. The 2021¬ÝIIA requires all new declarations to be checked.

Figure¬Ý8¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝNGOs‚Äô declarations on their funding sources

Source: ECA.

71 There is a weak audit trail for the Secretariat‚Äôs checks and data is affected by quality issues. In our analysis of a risk-based sample of 100¬Ýregistrants, we identified the following problems with the quality of the Secretariat‚Äôs checks.

- Weak audit trail. Although the Secretariat records when checks have been done, details are recorded only if problems are found. Of the 97¬ÝSecretariat checks examined, 49¬Ýincluded details on the checks done.

- Data quality issues. In three of the Secretariat’s checks, we identified problems with registrants’ data quality, namely a failure to declare financial and other information about clients, insufficient detail on description of interests, and inconsistency between the lobby budget and human resources.

The EUTR’s website has significant limitations regarding completeness and user-friendliness

72 OECD principle¬Ý5 states that ‚Äúdisclosure of lobbying activities should provide sufficient, pertinent information on key aspects of lobbying activities to enable public scrutiny‚Äù. According to the 2021¬ÝIIA (recital¬Ý5), Transparency concerning interest representation is important to allow citizens to follow the activities and be aware of the potential influence of lobbyists. A well-functioning and up-to-date website is also important to allow members and staff of the institutions to check whether lobbyists are registered before meeting them. The EUTR website contains information provided by lobbyists, see Box¬Ý4, and some of it is searchable.

73 We assessed the type of information about lobbyists available on the EUTR website, the searchability of this information, the extent to which it is possible to compare lobbyists, and the user-friendliness of the website. For comparison, we also looked at the websites of member states and selected NGOs that provide information on key aspects of lobbying activities, see Box¬Ý5.

Websites providing information on lobbying activities

German lobby register website

In the German lobby register, data can be accessed in a user-friendly format, statistical information is available, and data can be filtered and searched using several categories.

Website run by an NGO about EU lobbyists

Operated by an NGO, this online interactive database collects, harmonises and presents information extracted from the websites of the EUTR, Commission Directors-General, the Parliament, and the EU open data portal. Users can search, filter, and sort this information in a user-friendly way using interactive dashboards and scoreboards.

74 We noted that the EUTR website does contain the most recent detailed information provided by the lobbyists, but there are limitations.

- Information about lobbyists’ meetings only covers those with Commissioners and Directors-General of the Commission. There is no information about lobbyists’ meetings with staff of the Council, or with MEPs or staff of the Parliament. For the Parliament, some such information is published on its own website or on the online pages of individual MEPs. According to the Secretariat, the Parliament is currently developing a meeting publication tool, which is intended to be linked with the EUTR. The current search function as regards lobbyists is based on limited criteria and covers only certain categories. It is not possible to search for information focusing on lobbyists that certain members or staff have met. It is only possible to view information about one EUTR registrant at a time, and search results can only be organised according to lobbyist name, category of registration, registration date, and country head office. Results cannot be ranked by other useful criteria, such as largest lobby spenders, amount of EU grants received, lobbying resources, or number of meetings.

- The user-friendliness of the website is currently sub-optimal. The user interface is limited to simple search and filter query forms. It does not provide aggregated information on lobbyists and their activities in a way that allows users to interrogate the available data. Furthermore, it does not employ common online data presentation techniques, such as dynamically linked, interactive dashboards and scoreboards.

- For lobbyists which had been removed or suspended from the register, the information on their previous lobbying activities was not visible during the suspension nor when they had registered again. The information on lobbyists that have been suspended has been available since March¬Ý2023 on a dedicated sub-page. See Box¬Ý6.

Loss of historical information about lobbyists reduces transparency

One lobbyist in our sample was removed from the EUTR in May¬Ý2020 because it had not done the mandatory annual update. It registered again in June¬Ý2020, but the Secretariat gave it a new identification number. Information about all the lobbyist‚Äôs activities before May¬Ý2020 linked to the old identification number was no longer available on the EUTR‚Äôs public website. This loss of historical information about lobbyists reduces transparency.

We also found a case where a lobbyist implicated in ‚ÄúQatargate‚Äù was suspended from the EUTR in December¬Ý2022. During the suspension, information about its activities, budgets, and meeting data were not visible on the public website until March¬Ý2023, when information on suspended registrants started to be disclosed.

Conclusions and recommendations

75 We conclude that the EU transparency register provides useful information to allow citizens to follow lobbying practices, but weaknesses and gaps reduce the transparency of lobbying activities taking place in the three signatory institutions.

76 The 2021¬Ýinterinstitutional agreement on the transparency register is broadly consistent with international principles. There is a clear framework and a centralised entry point for lobbyists wishing to gain access to information on or influence the development of EU policies, decisions or law-making. The 2021¬Ýinterinstitutional agreement includes eligibility provisions for applicants and requires adherence of lobbyists to a common code of conduct. However, we found that enforcement measures to ensure that lobbyists comply with registration and information requirements are limited. The 2021¬Ýinterinstitutional agreement is not a legislative act and therefore cannot be used to impose sanctions on lobbyists, while they can be removed from the register in certain cases. See paragraphs¬Ý22 to¬Ý26.

77 The 2021¬Ýinterinstitutional agreement introduced the principle of conditionality, by which members or staff of signatory institutions are supposed to interact only with registered lobbyists. In practice, the institutions apply this principle in different ways. This has resulted in different approaches, including in relation to what constitutes a ‚Äòmeeting‚Äô, and ‚Äòmeeting with whom‚Äô, where registration of lobbyists in the transparency register would be a precondition for taking part in meetings or other activities.¬ÝOnly lobbying meetings with the highest-level decision-makers at the Council‚Äôs General Secretariat and the Commission are subject to this precondition. The Parliament does not apply the precondition to individual meetings with members and staff, except for certain meetings in the context of events and activities (e.g. committee hearings). See paragraphs¬Ý27 to¬Ý40.

Recommendation¬Ý1¬Ý‚Äì Strengthen and harmonise the implementation of the EUTR framework

The signatory institutions should strengthen and harmonise the existing framework, either through the upcoming review of the interinstitutional agreement or through their implementing decisions, by:

- providing a common definition of what constitutes a ‘meeting’ that captures all scheduled exchanges with lobbyists;

- specifying that at least the senior management with policy-making and decision-making responsibilities (director and above) should meet only registered lobbyists.

Target implementation date: July¬Ý2025

78 The three signatory institutions have taken different steps to increase transparency and encourage registration, by means of complementary measures. This has led to increased publication of information on meetings and activities with registered lobbyists. Nonetheless, such information is not published systematically. While it is not possible to require prior transparency register registration for spontaneous meetings, lobbying interactions of this type may also be aimed at influencing policies and would not be covered by the transparency register framework. See paragraphs¬Ý41 to¬Ý46.

Recommendation¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝPublish information on non-scheduled meetings with lobbyists

The signatory institutions should publish information on non-scheduled meetings where lobbying has taken place.

Target implementation date: July¬Ý2025

79 The transparency register‚Äôs Secretariat is a joint operational structure set up to manage the functioning operation of the transparency register. The Secretariat‚Äôs working arrangements are not formalised, and its joint nature requires there to be significant coordination. The Secretariat does not have rules of procedure specifying how the three institutions should work together to coordinate its work on tasks such as distribution of workload between institutions‚Äô staff or handover of cases. This increases the risk to operational efficiency. See paragraphs¬Ý49 to¬Ý58.

80 The Secretariat checks the quality of registrants‚Äô data either at the time of application, following complaints, or on an ad-hoc basis. This means that, once registered, only some of the registrants are subsequently checked to ensure that their data is up to date and compliant with any new requirements. While the Secretariat‚Äôs IT system flags data quality risks for specific registrants, these are not systematically followed up. We identified problems with data quality, such as duplicated registrations, inconsistent or incomplete financial data, and missing mandatory data. We also found insufficient documentation of checks. We noted recent improvements in the Secretariat‚Äôs checks. See paragraphs¬Ý59 to¬Ý68.

81 There is a risk that NGOs funded by third parties can avoid disclosing information about their funding sources by declaring that they represent only their own interests or the collective interests of their members. This is because registrants‚Äô choice of interest representation category is based on self-declaration. While there are some instructions for registrants about this, we did not find evidence that the Secretariat systematically checks these declarations. See paragraphs¬Ý69 to¬Ý71.

Recommendation¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝImprove data quality checks

To improve the quality of the transparency register’s data, the Secretariat should:

- plan regular data quality checks so that all registrants are checked at least once over a period of 3¬Ýyears, and systematically check those registrants where automated controls have identified risks;

- check completeness and accuracy of financial data on EU grants (e.g. cross-checking with the Commission’s accounting system);

- provide clear guidance and systematically check the validity of interest representation declared by all applicants and registrants;

- document all data quality checks in its IT system, including those checks which do not identify problems.

Target implementation date: End¬Ý2025

82 Disclosure of lobbying activities aims to provide sufficient and pertinent information on key aspects of lobbying activities to enable public scrutiny. However, the EUTR‚Äôs public website has significant limitations in this regard. Some important data, such as Parliament meetings, and historical data on re-registered entities is not available. Furthermore, the website does not provide aggregated data on lobbyists and their activities in a user-friendly, interactive way. See paragraphs¬Ý72 to¬Ý74.

Recommendation¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝImprove the user-friendliness and relevance of the transparency register‚Äôs public website

The Secretariat should improve the relevance and user-friendliness of the transparency register’s public website by:

- providing aggregated information on lobbyists and their activities in interactive dashboards and scoreboards, thereby allowing users to analyse and compare the data available from different sources;

- integrating and linking information about lobbyists in the transparency register with published information about their lobbying activities, including meetings with members and staff of the institutions (including MEPs);

- making available all historical information about lobbyists which have been removed or suspended from the transparency register, including their lobby meetings.

Target implementation date: End¬Ý2025

This report was adopted by Chamber V, headed by Mr Jan¬ÝGregor, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 27¬ÝFebruary¬Ý2024.

For the Court of Auditors

Tony Murphy

President

Annexes

Annex¬ÝI ‚Äì Definitions of lobbying

Source | Definition of lobbying |

|---|---|

Historical definition

| The Oxford English Dictionary records a meaning for the noun¬Ýlobby, dating back to at least¬Ý1640 and which is defined as a place for legislators and members of the public to meet and discuss matters. |

Academic literature

| Academic literature defines lobbying as a concerted effort to influence policy formulation and decision-making, with a view to obtaining some designated result from government authorities and elected representatives, usually carried out by organised groups or individuals with specific interests (Regulating lobbying: A global comparison, Chari et al.¬Ý2019). |

Public relations professionals

| One definition of “lobbying” provided by the Public Relations Institute of Ireland is “the specific efforts to influence public decision-making either by pressing for change in policy or seeking to prevent such change. It consists of representations to any public officeholder on any aspect of policy, or any measure implementing that policy, or any matter being considered, or which is likely to be considered by a public body”. |

Council of Europe

| According to the Council of Europe, “lobbying is generally understood as a concerted effort to influence policy formulation and decision-making with a view to obtaining some designated result from government authorities and elected representatives. In a wider sense, the term may refer to public actions (such as demonstrations) or ‘public affairs’ activities by various institutions (associations, consultancies, advocacy groups, think-tanks, NGOs, lawyers, etc.); in a more restrictive sense, it would mean the protection of economic interests by the corporate sector (corporate lobbying) commensurate to its weight on a national or global scene”. |

OECD | According to the OECD, “Lobbying is a natural part of the democratic process. By sharing expertise, legitimate needs, and evidence about policy problems and how to address them, different interest groups can provide governments with valuable insights and data on which to base public policies. Information from a variety of interests and stakeholders helps policy makers understand options and trade-offs, and can lead, ultimately, to better policies”. |

Annex¬ÝII ‚Äì Different financial disclosure requirements

Types of interest representatives:

(A) Promoting their own interests or the interests of their members

(B) Advancing interests of clients (intermediaries)

(C) Do not represent commercial interests

Financial data and information | (A) | (B) | (C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Newly formed entity (Y/N) | ‚úî | ‚úî | ‚úî | ||

Most recent financial year | ‚úî | ‚úî | ‚úî | ||

Closed year start and closed year end | ‚úî | ‚úî | ‚úî | ||

Estimate of annual costs relating to activities covered by the EUTR | ‚úî | ‚úò | ‚úò | ||

Estimated total annual revenue | ‚úò | ‚úî | ‚úò | ||

Total budget | ‚úò | ‚úò | ‚úî | ||

Complementary information | ‚úî | ‚úî | ‚úî | ||

Hired intermediaries to carry out covered activities on its behalf | In the most recent closed financial year | Name of intermediary, representation costs | ‚úî | ‚úò | ‚úò |

In the current financial year | Name of intermediary, representation costs | ‚úî | ‚úò | ‚úò | |

Relevant clients on behalf of whom the applicant had engaged in representation activities at the EU institutions | In the most recent closed financial year | Full list of clients specifying: (a) their full names (no acronyms, no generic names), (b) revenue, and (c) EU legislative proposals, policies or initiatives targeted by the covered activities on behalf of this specific client (corresponding to the entries under heading 9 of the registration form) | ‚úò | ‚úî | ‚úò |

In the current financial year | Client’s name | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | |

Funding | For each contribution exceeding 10¬Ý% of total budget AND above ‚Ǩ10¬Ý000 | Source of funding by category (EU funding and grants, public financing, non-EU grants, donations, members‚Äô contributions) Contributor‚Äôs name, amount, source of funding | ‚úò | ‚úò | ‚úî |

Grants contributing to the applicant’s/ | In the most recent closed financial year | Source, amount, total amount of EU grants | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

In the current financial year (Y/N) | Source, amount, total amount of EU grants | ‚úî | ‚úî | ‚úî | |

‚úîRequired | |||||

‚úòNot required | |||||

Source: 2021¬ÝIIA and the Guidelines for applicants and registrants.

Annex¬ÝIII ‚Äì Types of registrants and declared interest representation

Source: ECA, based on 2021¬ÝIIA and the EUTR.

Abbreviations

ABAC: Accrual-based¬Ýaccounting system

EUTR: EU Transparency Register

IIA: Interinstitutional agreement

NGO: Non-governmental organisation

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

TR-ADMIN: EUTR Secretariat`s back-office IT system

Glossary

Applicant: Any lobbyist that applies to be entered in the register.

Client: Lobbyist that has entered into a contractual relationship with an intermediary for the purpose of that intermediary advancing that interest representative’s interests by carrying out covered activities.

Conditionality: Principle whereby, for interest representatives to be allowed to lobby, they must first be included in the EUTR.

Covered activities: Lobbying activities included in the scope of the IIA.

Interest representative: Any natural or legal person, or formal or informal group, association or network, that engages in lobbying activities covered by the interinstitutional agreement on the EUTR.

Interinstitutional agreement: Jointly agreed document regulating certain aspects of consultation and cooperation between EU institutions.

Intermediary: Lobbyist that advances the interests of a client by carrying out lobbying activities.

Registrant: Any lobbyist whose name is included in the EUTR with an entry in the register.

Audit team

The ECA’s special reports set out the results of its audits of EU policies and programmes, or of management-related topics from specific budgetary areas. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to be of maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by Audit Chamber V Financing and administration of the EUV Financing and administration of the EU, headed by ECA Member Jan¬ÝGregor. The audit was led by ECA Member Jorg¬ÝKristijan¬ÝPetrovic, supported by Martin¬ÝPuc, Head of Private Office and Mirko¬ÝIaconisi, Private Office Attach√©; Margit¬ÝSpindelegger, Principal Manager; Attila¬ÝHorvay-Kovacs, Head of Task; Gediminas Macys, Quirino¬ÝMealha, Nita¬ÝTennil√§, Elitsa¬ÝPavlova and Tetiana¬ÝLebedynets, Auditors. Jennifer¬ÝSchofield provided linguistic support.

From left to right: Gediminas Macys, Attila Horvay-Kovacs, Elitsa Pavlova, Tetiana Lebedynets, Mirko Iaconisi, Jorg Kristijan Petrovic, Margit Spindelegger, Martin Puc, Nita Tennilä, Jennifer Schofield and Quirino Mealha.

COPYRIGHT

© European Union, 2024

The reuse policy of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is set out in ECA Decision No¬Ý6-2019 on the open data policy and the reuse of documents.

Unless otherwise indicated (e.g. in individual copyright notices), ECA content owned by the EU is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC¬ÝBY¬Ý4.0) licence. As a general rule, therefore, reuse is authorised provided appropriate credit is given and any changes are indicated. Those reusing ECA content must not distort the original meaning or message. The ECA shall not be liable for any consequences of reuse.

Additional permission must be obtained if specific content depicts identifiable private individuals, e.g. in pictures of ECA staff, or includes third-party works.

Where such permission is obtained, it shall cancel and replace the above-mentioned general permission and shall clearly state any restrictions on use.

To use or reproduce content that is not owned by the EU, it may be necessary to seek permission directly from the copyright holders.

-Figures 2, 5 and 7 – Icons: these figures have been designed using resources from https://flaticon.com. © Freepik Company S.L. All rights reserved.

Software or documents covered by industrial property rights, such as patents, trademarks, registered designs, logos and names, are excluded from the ECA’s reuse policy.

The European Union’s family of institutional websites, within the europa.eu domain, provides links to third-party sites. Since the ECA has no control over these, you are encouraged to review their privacy and copyright policies.

Use of the ECA logo

The ECA logo must not be used without the ECA’s prior consent.

| ISBN 978-92-849-1977-2 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/47356 | QJ-AB-24-006-EN-N | |

| HTML | ISBN 978-92-849-1927-7 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/574437 | QJ-AB-24-006-EN-Q |

Endnotes

1 Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union.

2 OECD (2021), Lobbying in the 21st Century Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021. Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2.

3 Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2 and explanatory memorandum, point B.1.10.

4 Germany, Lobbyregistergesetz (Lobbying Register Act) 2021, Ireland, Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015, OECD (2012), Private Interests, Public Conduct: The Essence of Lobbying, Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2 and explanatory memorandum.

6 Ibid., recital¬Ý7.

7 Ibid., Article¬Ý5.

8 Ibid., Article¬Ý1.

9 Ibid, Article¬Ý7.

12 European Economic and Social Committee, Decision¬ÝC.6 of 21¬ÝMarch¬Ý2023.

13 Political declaration on the occasion of the adoption of the Interinstitutional Agreement on a mandatory transparency register.

14 European Parliament Research Service, Transparency Register: Who is lobbying the EU (infographic), 2018, updated in¬Ý2021, and Greek lobbying regulation law 4829/2021 adopted afterwards.

15 Statement of the Conference of Presidents, 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2022, and Corruption scandal: MEPs insist on reforms for transparency and accountability, 15¬ÝDecember¬Ý2022.

16 European Parliament decision 2023/2095(REG), Amendment¬Ý13, Parliament‚Äôs Rules of Procedure, Annex¬ÝI ‚Äì Article¬Ý5¬Ýa (new).

17 Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2 and explanatory memorandum.

18 OECD, Lobbying in the 21st century: Transparency, integrity and access, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021, OECD, Recommendation of the Council on principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying OECD/LEGAL/0379; and Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec(2017).

19 Recommendation of the Council Principles for transparency and Integrity in Lobbying OECD/LEGAL/0379.

21 Ibid., Articles¬Ý3 and¬Ý4.

22 Ibid., Articles¬Ý7 and¬Ý8.

23 Ibid., Article¬Ý6, Annexes¬ÝI and¬ÝIII.

24 Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, OECD/LEGAL/0379 Principle¬Ý9.

25 Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2, Principle¬Ý15.

28 Council Staff Note¬Ý35/21section¬Ý2 (not publicly available).

31 European Parliament decision 2023/2095(REG), Amendment¬Ý13, Parliament‚Äôs Rules of Procedure, Annex¬ÝI ‚Äì Article¬Ý5¬Ýa (new).

32 Commission Decisions 2014/838/EU, Euratom, 2014/839/EU, Euratom and 2018/C¬Ý65/06.

34 Chapter¬ÝVII Guidelines on Stakeholder Consultation, Better Regulation Guidelines of the European Commission (SWD¬Ý(2017)350).

35 First meeting of the Management Board on 24¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2021.

37 Ibid., Article¬Ý8(3).

38 Ibid., Article¬Ý8(2).

40 Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2017)2 and explanatory memorandum, Principle¬Ý8.

43 Recommendation of¬Ýthe Council on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, OECD/LEGAL/0379, Principle¬Ý5.