Executive summary

I Labels provide consumers with information about the content of their food and help them make informed purchasing decisions. The European Union has labelling rules in place with the aim of providing citizens with information about the content and characteristics of food products.

II We carried out this audit because of the growing interest in food information among consumers, the EU institutions and other stakeholders. We assessed whether food labelling in the EU helps consumers make informed decisions when purchasing food. We checked the EU¬Ýlegal framework and how consumer understanding of labels is monitored. We also looked at member states‚Äô control systems, how they check that food companies comply with labelling rules, and how the Commission and member states report on these checks.

III Overall, we conclude that food labelling in the EU can help consumers make better-informed decisions when purchasing food, but there are notable gaps in the EU legal framework as well as weaknesses in the monitoring, reporting, control systems, and sanctions. This leads to consumers being confronted with labels that can be confusing or misleading, or that they do not always understand.

IV We found that the EU¬Ýlegal framework provides for essential information on food labels but 7 out of 11 planned updates have not been completed. Member states have implemented different initiatives to compensate for some missing elements in the EU framework. This limits consumers‚Äô ability to make informed choices and causes inequity in consumer access to some food-related information across the EU.

V We also found that new labelling practices by food companies add complexity and can confuse or mislead consumers. The Commission and member states do not track consumer needs or their understanding of labels in a systematic way. However, there is evidence that consumers do not always understand labels. To address this, informing and educating consumers is key, but awareness-raising campaigns for consumers carried out by member states are sporadic.

VI Member states are required to set up control systems and check whether food companies implement labelling rules correctly. These systems are in place but checks on voluntary information and online retail are not sufficient. As regards infringements, fines are not always dissuasive, effective or proportionate. Member states and the Commission also report on the outcome of their checks, but we found that reporting arrangements are cumbersome and the added value is not clear.

VII We recommend that the Commission should:

- address the gaps in the EU¬Ýlegal framework for food labelling;

- step up efforts to analyse labelling practices;

- monitor consumer expectations and take action to improve their understanding of food labelling;

- strengthen member states’ checks on voluntary labels and online retail;

- improve reporting on food labelling.

Introduction

What is food labelling?

01 Labels provide consumers with information about the content of their food and help them make informed purchasing decisions. The EU definition of a label is “any tag, brand, mark, pictorial or other descriptive matter, written, printed, stencilled, marked, embossed or impressed on, or attached to the packaging or container of food”1.

02 Labels provide information regarding the nutritional value, potential risks (allergens) and safe consumption of a product (date marking). They are also an important means of advertising, used to make the product more attractive to potential buyers by emphasising certain qualities like being healthy, organic or gluten-free.

03 Consumers’ right to comprehensive and accurate information regarding their food has become increasingly relevant in recent years, with a growing interest in health and wellness, sustainability and transparency. At the same time, marketing practices have also evolved, and the choice of foods has broadened.

Food labelling rules

04 The EU has a legal framework in place with the aim of providing citizens with information about the content and characteristics of food products, mostly through labelling practices. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union requires the EU to ensure a high level of consumer protection by protecting the health, safety and economic interests of consumers, as well as by promoting their right to information2.

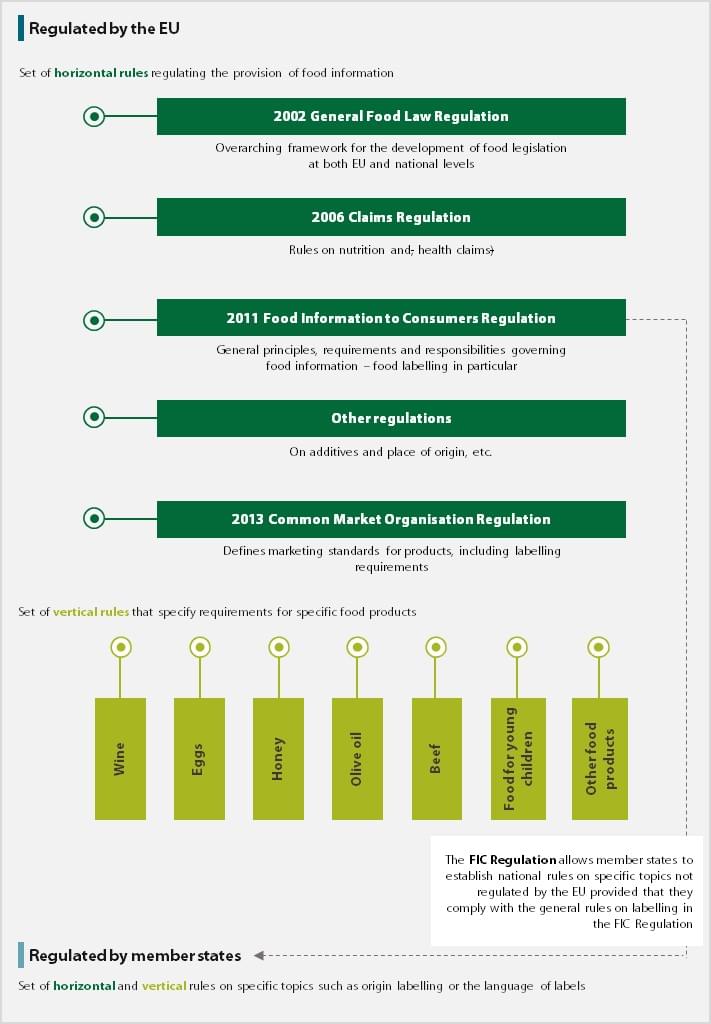

05 The provision of food information to consumers is regulated through a set of horizontal rules (see Figure¬Ý1), such as the 2002 General Food Law Regulation3, the 2006 Claims Regulation4 and the 2011 Food Information to Consumers Regulation (FIC¬ÝRegulation). The latter sets out that the information must be accurate, clear, easy to understand, and not misleading, and should not be ambiguous or confusing5. Food labelling in the EU is also regulated through a set of vertical rules that set requirements for specific food products (wine, eggs, honey, olive oil, food intended for young children, etc.).

Figure¬Ý1¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝFood labelling rules in the EU

Source: ECA.

06 Aside from these EU rules, the FIC¬ÝRegulation allows member states to establish national rules on specific topics such as origin labelling or the language of labels. This information must comply with the general rules on labelling in the FIC¬ÝRegulation (see paragraph¬Ý05).

Types of information on labels

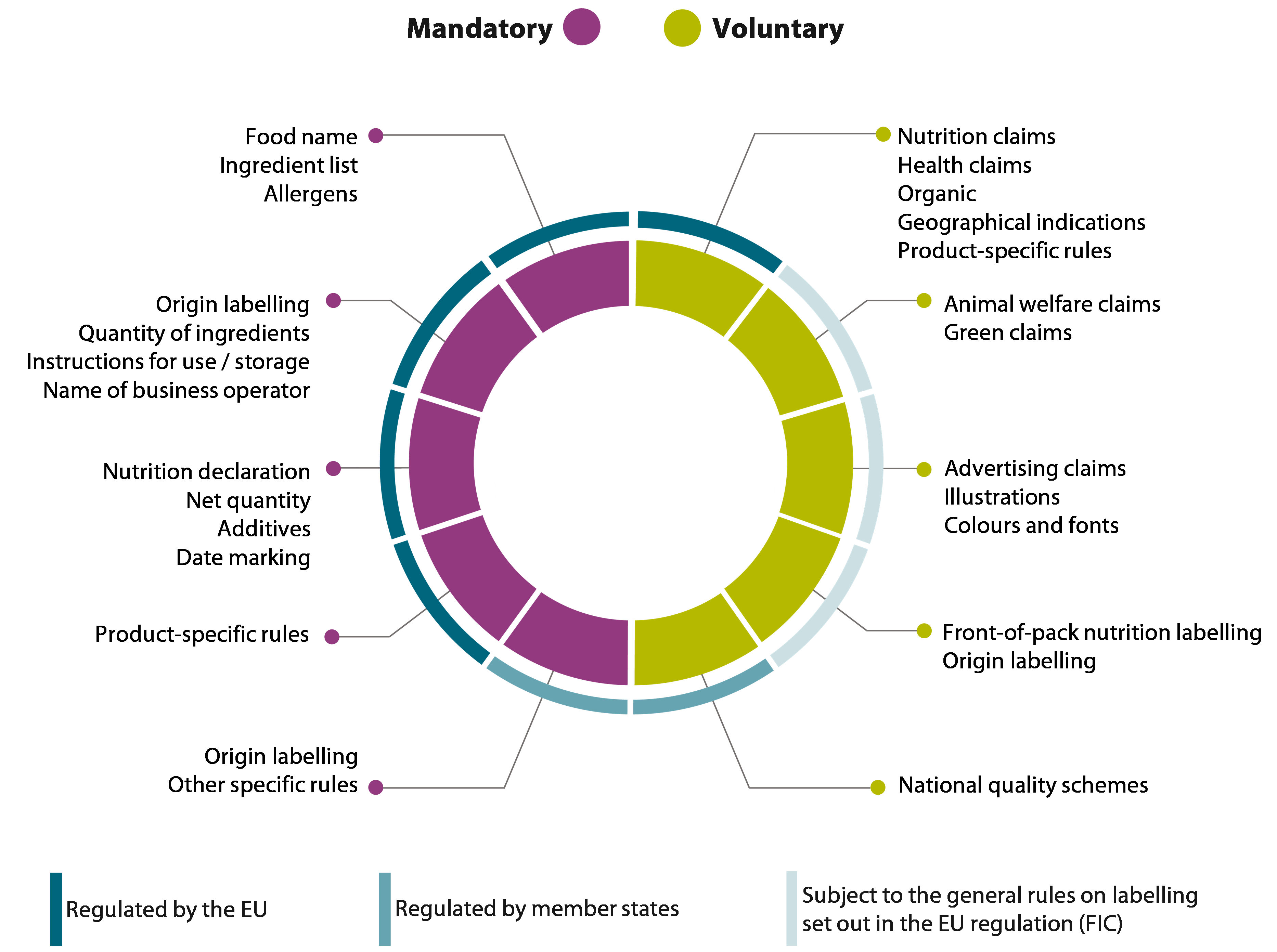

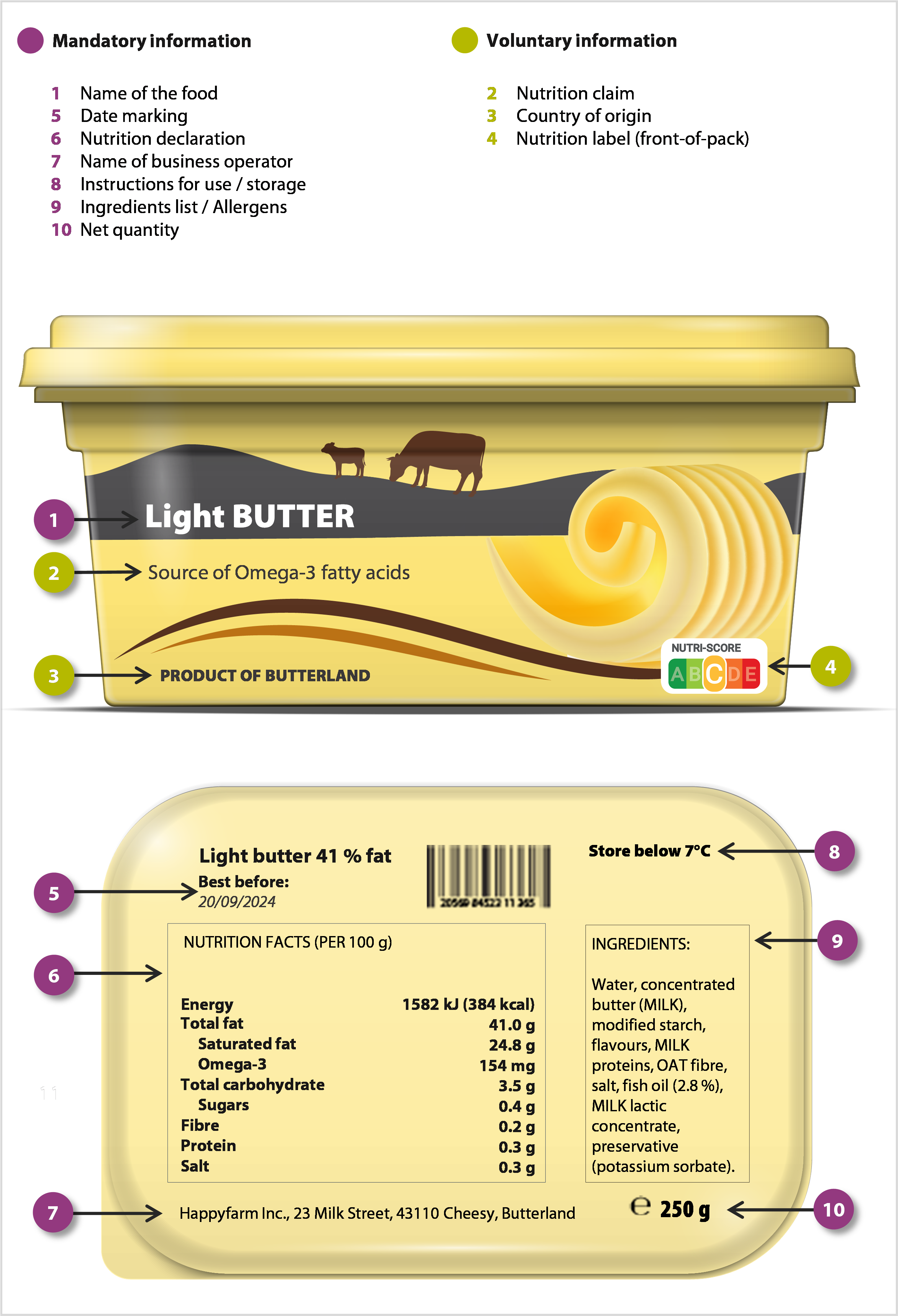

07 The FIC¬ÝRegulation requires labels to include certain mandatory information for prepacked foods (food put into packaging before sale). It is also common to include ‚Äúvoluntary information‚Äù to inform and appeal to consumers. This information may be included as long as it adheres to the general rules of the FIC¬ÝRegulation (see paragraph¬Ý05).

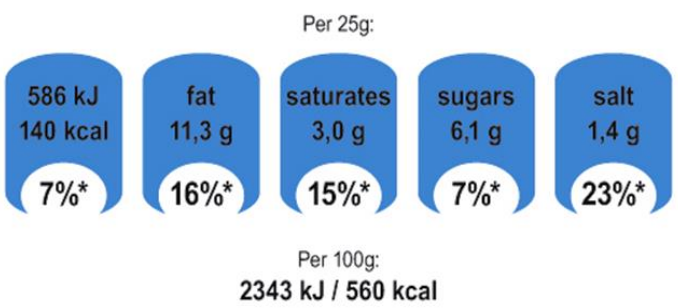

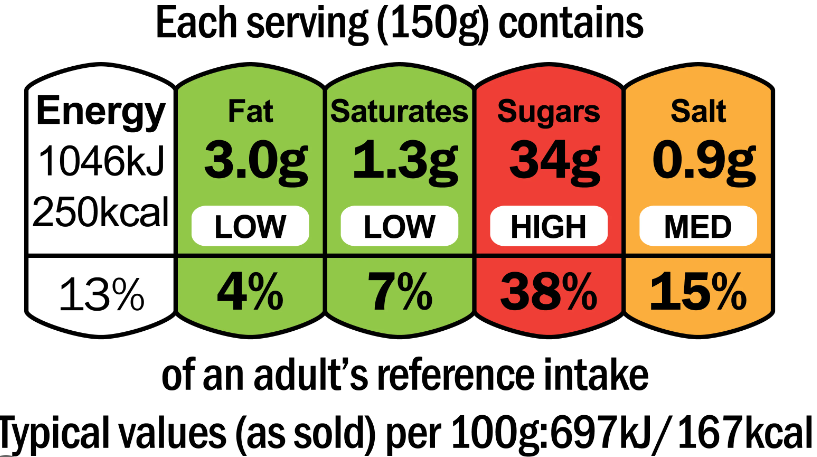

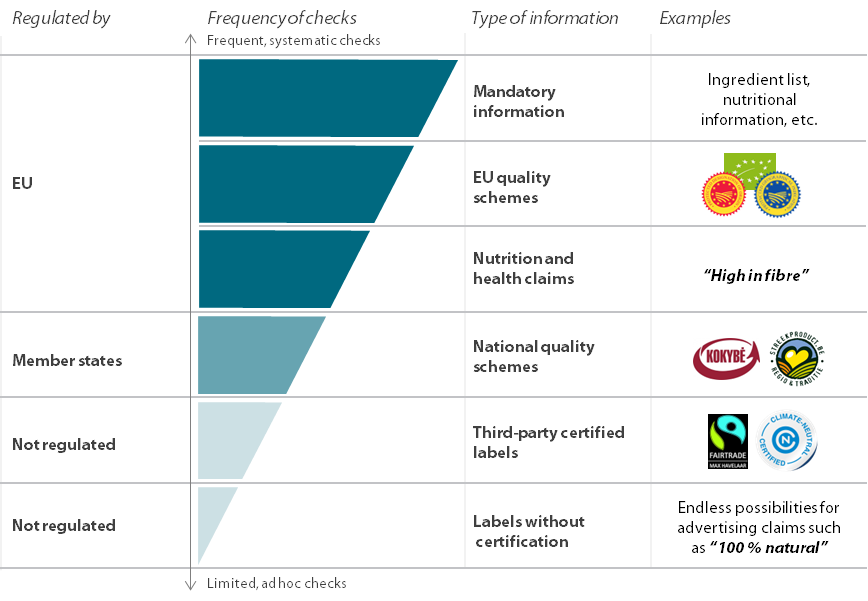

08 While mandatory information is mostly focused on health and safety, voluntary elements are broader in scope, ranging from green claims to illustrations ‚Äì as shown in Figure¬Ý2. Figure¬Ý3 illustrates how this is implemented in practice.

Figure¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝOverview of what constitutes mandatory and voluntary information, and how it is regulated

Source: ECA.

Figure¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝExample of mandatory and voluntary food labelling on a product

Source: ECA.

Roles and responsibilities

09 There are various entities dealing with food labelling in the EU.

- Food business operators (referred to as “food companies”) must ensure that their products fulfil food law requirements.

- Member states enforce food law and have to monitor and check that food companies comply with the relevant requirements at all stages of production, processing and distribution. For that purpose, as per the Official Controls Regulation6, they maintain a system of controls, as well as rules on sanctions applicable to infringements of food law. Member states have to report annually to the Commission on the implementation of their official controls.

- The Commission has to monitor the performance of the EU legal framework on food labelling and can propose updates to the framework. It also has to check that the control systems at national level are effective and maintain the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed online application (iRASFF), where member states must report food-related risks.

- The European Food Safety Authority provides independent scientific and technical advice to the Commission in fields which can have a direct or indirect impact on food labelling.

Audit scope and approach

10 This report examines whether food labelling in the EU helps consumers make informed decisions when purchasing food. We checked the EU¬Ýlegal framework and how consumer understanding of labels is monitored. We also looked at member states‚Äô control systems, how they check that food companies comply with labelling rules, and how the Commission and member states report on these checks. The audit focused specifically on the labelling of prepacked foods.

11 We carried out this audit because of the growing interest in food information among consumers, the EU institutions and other stakeholders. Consumers’ choices made on the basis of labels may also have consequences for their health and wellbeing. The Commission announced a revision of the FIC Regulation in the Farm to Fork strategy. We expect our findings and recommendations to help the discussion on this revision.

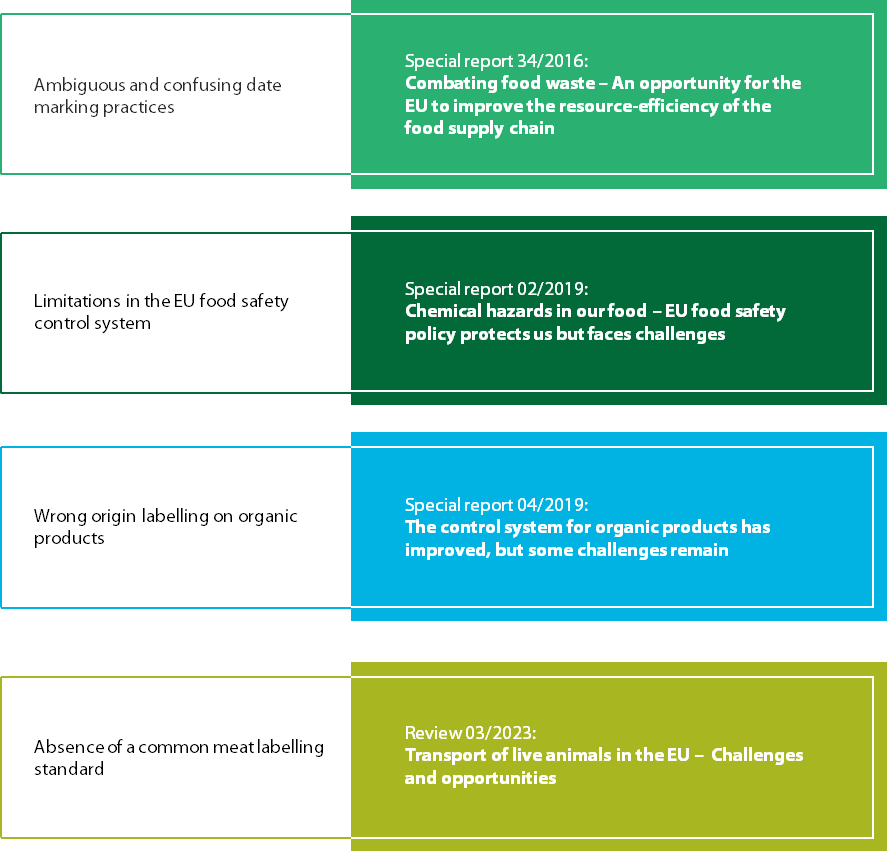

12 Previous ECA work has not specifically covered the topic of food labelling. However, our audit complements earlier reports. In 2019, we looked at how food safety policy protects citizens from chemical hazards7 and at the control system for organic products8. We also addressed date marking in our special report on food waste9 and meat labelling in a recent review on the transport of live animals10 (see Figure¬Ý4).

Figure¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝThe ECA‚Äôs audit work since 2016 related to food labelling and relevant issues raised

Source: ECA.

13 The audit covered the period between 2011 and 2023. We met with the Commission (Directorate-General for¬ÝHealth and Food Safety, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development) and interviewed relevant authorities in Belgium, Italy and Lithuania. These member states were selected based on geographical balance, the complexity of food labelling schemes and the coverage of some key labelling topics (e.g. origin labelling and front-of-pack nutrition labelling).

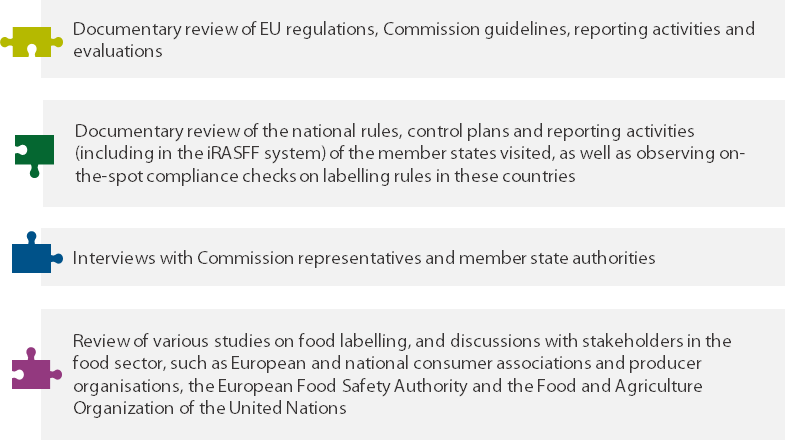

14 We obtained evidence from various sources, as presented in Figure¬Ý5.

Source: ECA.

Observations

The EU legal framework provides for essential information on food labels, but it has notable gaps

15 We examined the current EU legal framework on food labelling, and looked at what action the Commission has taken to review and propose updates to the framework. We expected:

- the EU legal framework to provide for essential food labelling information;

- the Commission to propose timely and appropriate updates of the framework, as provided for in the FIC and Claims¬Ýregulations.

The EU legal framework provides for essential information on food labels

16 Our documentary review showed that the essential information on food labels within the EU legal framework is provided in the FIC Regulation and complemented by the Claims Regulation and the EU‚Äôs vertical rules. The FIC¬ÝRegulation came into force at the end of 2014. It integrated different pieces of legislation into one harmonised set of rules and strengthened requirements regarding food labelling to help consumers make informed choices. It also included definitions of some key concepts (e.g. legibility, date of minimum durability), and made certain information mandatory. For example, it became mandatory to include information on allergens, on nutrition (stating the energy value and amounts of fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugars, protein and salt per 100¬Ýg or per 100¬Ýml) and on how to store products.

17 The Claims¬ÝRegulation has applied since July¬Ý2007 and was a major step in regulating nutrition and health claims in commercial communications about food. We found that it helps to protect consumers from misleading and unsubstantiated claims. For example, it provides a list of permitted claims that food companies can use on products that meet the relevant conditions.

18 A set of vertical rules include labelling requirements for specific categories of food. These define, for example, that it is mandatory to mention the production or farming method, the origin, the variety or how a product can be named.

19 Thus, overall, the EU legal framework constitutes a basis for providing consumers with essential information on labels and can help them make better-informed decisions. Our discussions with stakeholders and member state authorities confirmed this.

Delayed updates of the legal framework limit consumers’ ability to make informed choices

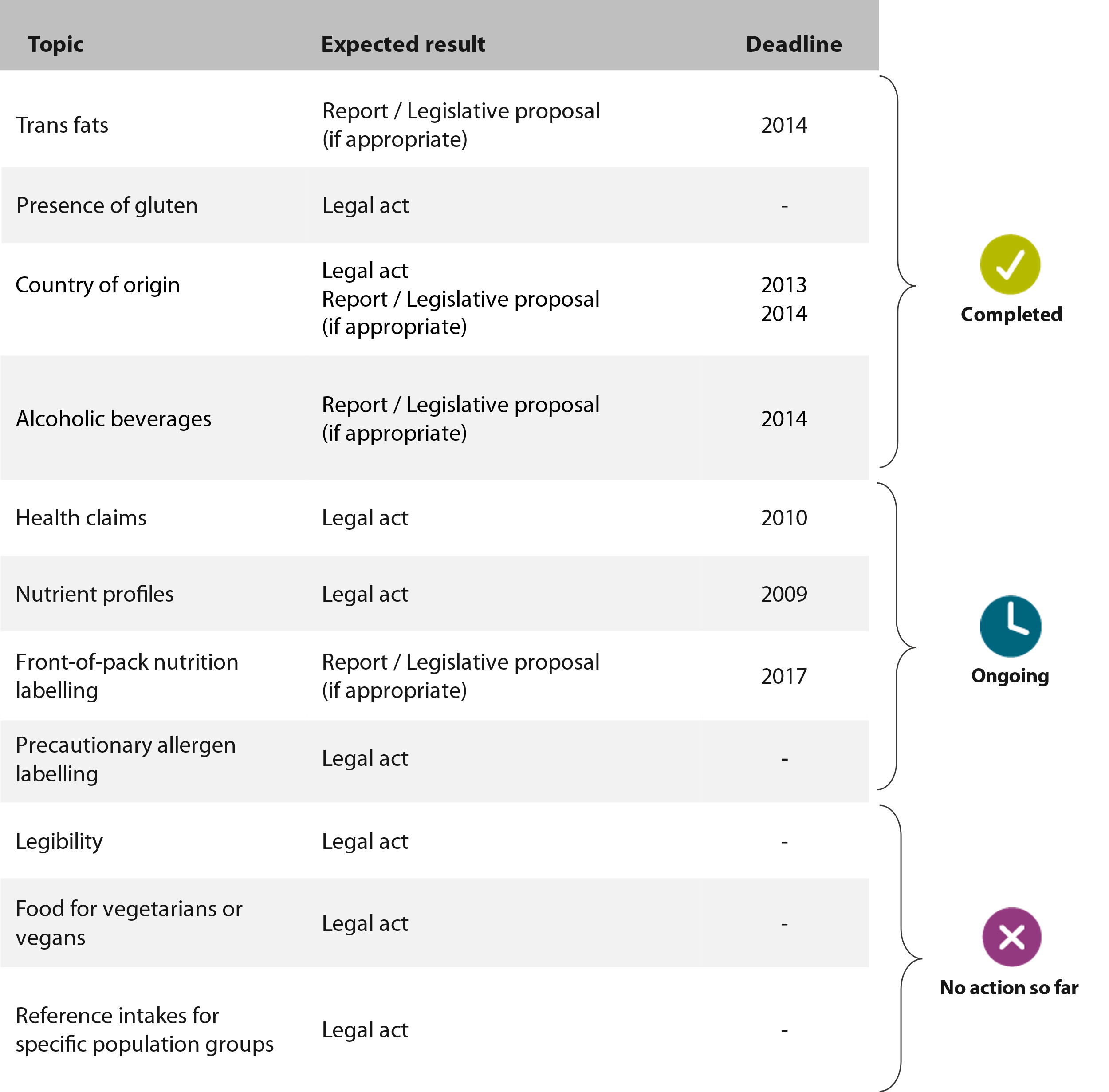

20 The FIC and Claims regulations required the Commission to take action (in the form of reports, legal acts and legislative proposals) on 11¬Ýtopics. By September¬Ý2024, the Commission had concluded its work on only 4 of the 11¬Ýtopics (see Figure¬Ý6 and Annex¬ÝI).

Figure¬Ý6¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝAction to be taken by the Commission according to the FIC and Claims regulations

21 The Commission published a report on trans fats in December¬Ý2015 and a regulation was adopted in 2019 setting a maximum limit for trans fats in food. Trans fats are unsaturated fatty acids, a high consumption of which increases the risk of heart disease.

22 The Commission also adopted an implementing act on the statements that can be used for food suitable for people who are intolerant to gluten, such as “gluten-free” or “very low gluten”11.

23 For country of origin, as provided for in the FIC Regulation, the Commission adopted rules for the mandatory indication of origin for certain food products in 2013 and 2018. In its 2020 Farm to Fork strategy, the Commission announced that it would consider proposing that mandatory origin or provenance indications be extended to certain products. By September 2024, the Commission had not yet published a proposal. Seven EU member states (Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal and Finland) have adopted national mandatory labelling schemes for certain food products. This causes unequal consumer access to some food-related information across the EU.

24 Alcoholic beverages were exempt from having to include the list of ingredients or a nutrition declaration. In 2017 and in line with the FIC Regulation, the Commission published a report on the labelling of alcoholic beverages, and in 2019 signed two memoranda of understanding with the beer and spirits sectors. In 2021, the co-legislators also adopted a regulation12 which required the ingredient list and nutrition declaration of wine and aromatised wine products to be included. As part of Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, adopted in February 2021, the Commission announced a proposal for mandatory labelling of alcoholic beverages to contribute to cancer prevention. In the absence of harmonised rules at EU level, some member states have started implementing their own alcohol labelling initiatives (such as mandatory health warning labels on alcohol in Ireland or pregnancy-related warning labels in Lithuania), which hinders consumers’ equal access to some food-related information across the EU.

25 The Commission’s work on the other topics is either ongoing or has not yet started, which is the case for legibility, food for vegetarians or vegans, and reference intakes for specific population groups. This limits consumers’ ability to make informed choices and causes inequity in consumer access to some food-related information across the EU, as explained in the following sub-sections.

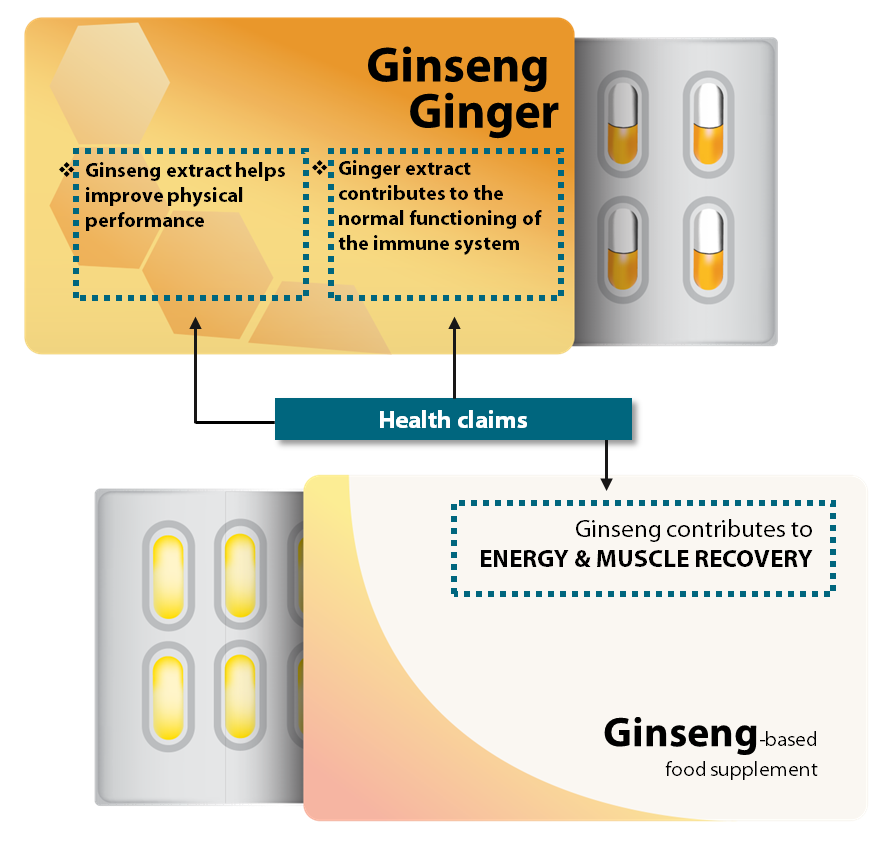

Lack of a list of EU-authorised health claims on botanical products

26 Many food products claim to have positive effects on our health ‚Äí these types of statements are known as ‚Äúhealth claims‚Äù. After the scientific assessment of 4¬Ý637¬Ýclaims used in the EU, the Commission published a regulation in May¬Ý2012 establishing a list of 222¬Ýpermitted health claims regarding vitamins, minerals or other non-plant substances (see Figure¬Ý7 for types of authorised health claims).

Figure¬Ý7¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝFive types of health claim authorised by the Commission

Source: ECA, based on Regulation¬Ý432/2012, and the EU register of health claims.

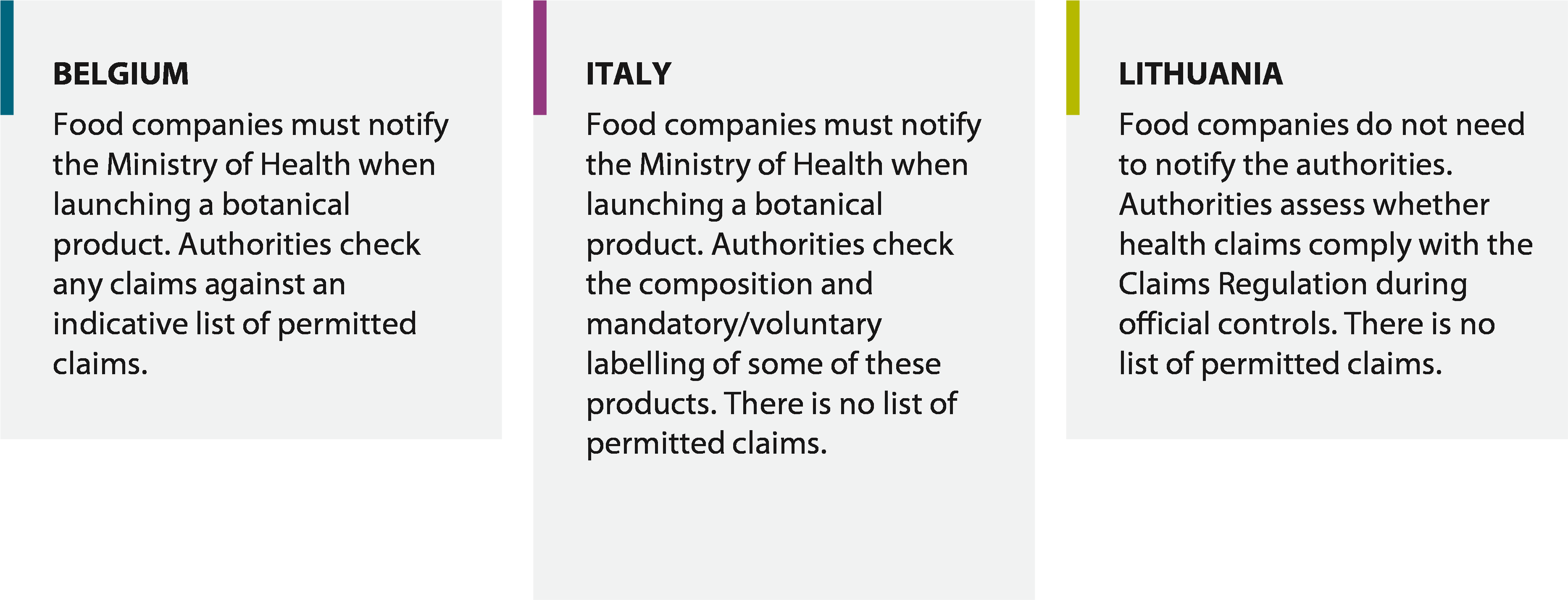

27 The Commission halted the scientific assessment of a sub-category of health claims related to plant substances or ‚Äúbotanicals‚Äù because studies demonstrating the impact of these substances on people, which were required to assess their effectiveness, were not available. In 2023, the European Parliament insisted on the urgent need to evaluate the claims that have been pending since 2010. Despite this, the 2 078¬Ýbotanical claims relating to plant substances remain ‚Äúon hold‚Äù.

28 In the absence of a list of EU-authorised botanical claims, consumers are exposed to claims which are not supported by scientific assessment or are potentially misleading (see examples in Figure¬Ý8). Member states have their own approaches to these claims (see Figure¬Ý9), which may further increase consumers‚Äô confusion.

Figure¬Ý8¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝExamples of botanical claims not supported by EU scientific assessment

Source: ECA.

Figure¬Ý9¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝDiffering approaches to botanical claims in the member states we covered

Source: ECA.

Lack of EU rules on nutrient profiles

29 EU food labelling rules currently allow the use of nutrition and health claims even for products that are high in fat, sugar and/or salt (e.g. ‚Äúrich in vitamin¬ÝC‚Äù on a product high in sugar). Consumers who are trying to make healthier choices might therefore inadvertently consume products containing high amounts of unhealthy nutrients (see Figure¬Ý10).

Figure¬Ý10¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝExamples of products with authorised claims that are also high in fat and sugar

Source: ECA.

30 Nutrient profiles are expected to help avoid such situations. They set a limit for these nutrients, above which nutrition and health claims would be restricted or prohibited. According to the Claims Regulation, nutrient profiles should have been put in place by 2009. The WHO published an initial nutrient profile model in 2015 (updated in March¬Ý2023) and has pointed out that nutrient profiling is particularly useful for foods marketed to children. Stakeholders like the European Parliament and consumer organisations have supported this measure.

31 Until 2020, the Commission had made little progress, citing the difficulty in obtaining the necessary support from member states. The Farm to Fork strategy put nutrient profiles back on the agenda in 2020 and envisaged their establishment by the end of 2022. However, as of September¬Ý2024, the Commission had still not introduced them. According to the Commission, the nature of the topic means that a legislative proposal would be difficult to achieve in the foreseeable future.

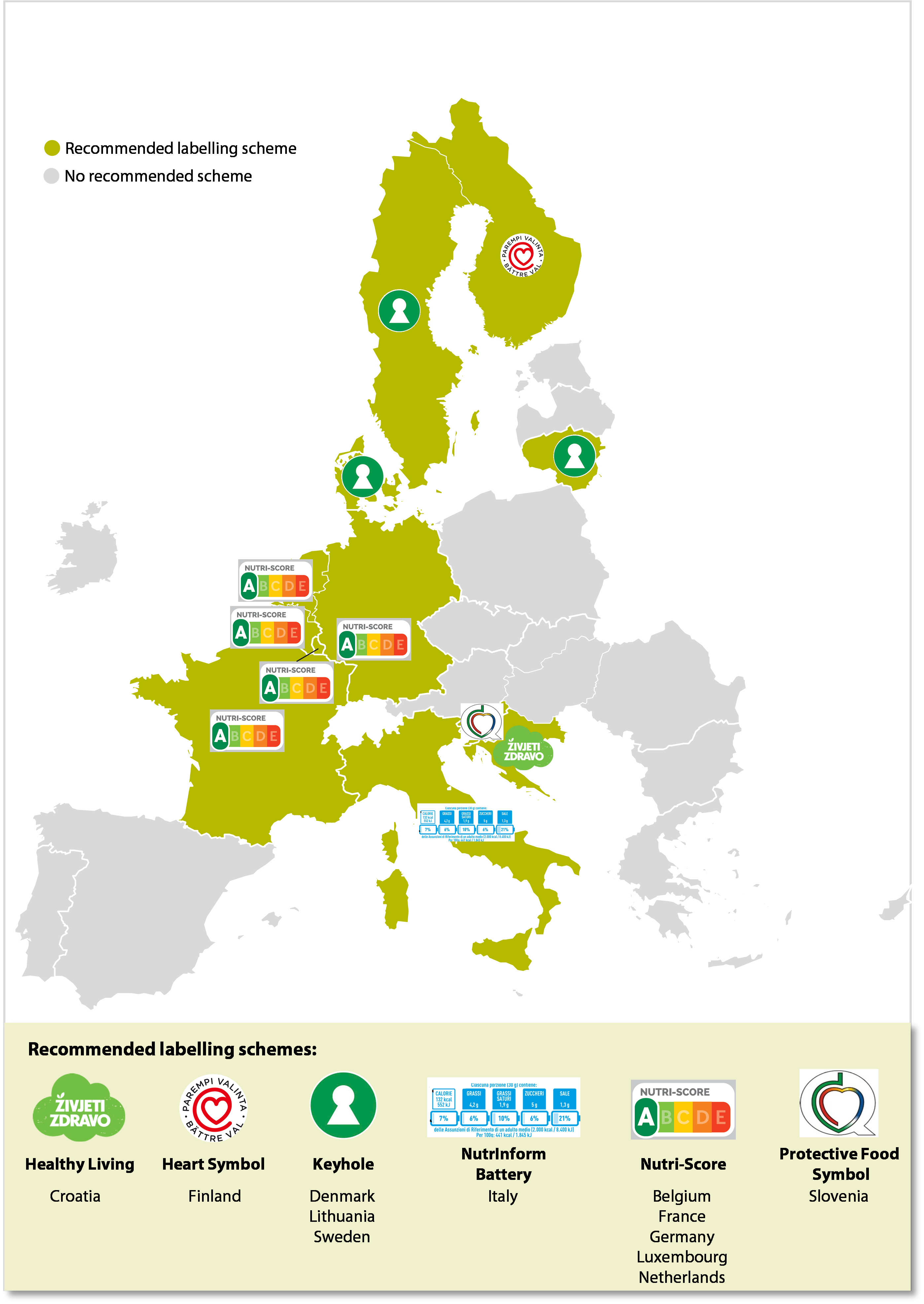

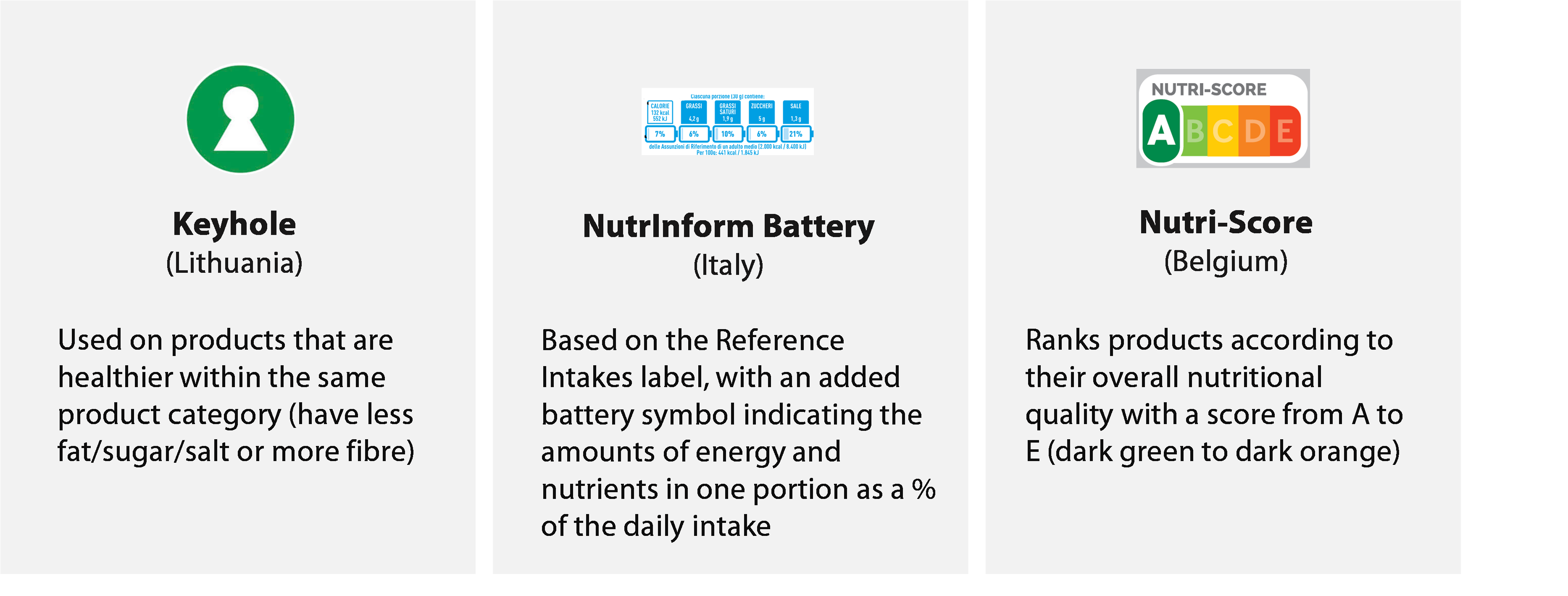

Lack of harmonised front-of-pack nutrition labelling

32 In addition to the mandatory nutrition declaration (see paragraph¬Ý16), nutrition information can be included on the front of pack on a voluntary basis. A 2020 Commission report shows that front-of-pack nutrition labelling can help consumers identify healthier food options and potentially help prevent diet-related diseases. Figure¬Ý11 provides examples of different front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes recommended by national public authorities.

Figure¬Ý11¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝExamples of front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes recommended by member states

Source: ECA.

33 Such schemes, which are recommended by public authorities, support consumers in making informed choices by providing illustrations or information about the nutritional quality of a food. There are currently no labels that indicate the processing level of foods, although scientific evidence suggests that consuming high quantities of ultra-processed food increases the risk of developing diet-related diseases.

34 The Commission was expected to report on the use of additional forms of expressing and presenting nutrition information by 2017 and to present proposals to modify the EU¬Ýrules if appropriate. In its report, published in 2020, the Commission concluded that ‚Äúit seems appropriate to introduce a harmonised mandatory FOP [front-of-pack] nutrition labelling at EU-level‚Äù. In the 2020 Farm to Fork strategy, the Commission announced that it would present a legislative proposal on this by the end of 2022, but no proposal has been put forward.

35 Although many consumer and producer organisations support harmonisation, there is no consensus among stakeholders on which existing labelling scheme to choose and whether it should be mandatory. A variety of front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes have emerged (Annex¬ÝIII) and are backed by several member states. Figure¬Ý12 shows the schemes recommended in the three countries we visited, along with their main characteristics. The Commission identified that all three schemes have advantages, but may also come with drawbacks (e.g. not easy to understand for consumers or do not show nutritional information) in recent reports.

Figure¬Ý12¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝExamples of some front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes and their characteristics

Source: ECA, based on the JRC report Front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes: an update of the evidence, 2022.

36 The debate around front-of-pack nutrition labelling has become polarised. For example, certain member states now discourage food companies from using the Nutri-Score scheme although it is recommended in other member states (see example in Box¬Ý1). The co-existence of multiple schemes in the EU can cause market fragmentation and confuse consumers.

Controversy over front-of-pack nutrition labelling in Italy

The only front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme that the Italian authorities recommend is the NutrInform Battery. In 2022, the Italian Competition Authority issued administrative decisions (including fines) against food companies using the Nutri-Score label. It argued that food companies which display the Nutri-Score label without further explanation of the score could mislead consumers. Following the decisions, several companies agreed to either drop the Nutri-Score label or add additional information.

Lack of harmonised rules on precautionary allergen labelling

37 The FIC¬ÝRegulation requires food allergens to be emphasised in the ingredient list, to ensure that consumers are aware of potential risks. However, sometimes the unintentional presence of small amounts (or traces) of allergens, which may still affect some people with allergies, is unavoidable.

38 Many food companies therefore use precautionary allergen labelling, such as “may contain [allergen]”, or “produced in a factory that handles [allergen]” but there are no harmonised rules at EU level. This can be confusing for consumers, who have to navigate numerous labelling formats. Moreover, food companies apply the “may contain” statement too liberally, in order to play it safe, and at times the use of this statement is not based on risk assessments quantifying the presence of allergens. Food companies’ abuse of the “may contain” statement limits the choice of allergen-sensitive consumers.

39 The FIC¬ÝRegulation requires the Commission to adopt implementing acts on precautionary allergen labelling. The Commission has started addressing the topic through the 2022 revision of its notice on good hygiene practices in food safety management systems, as well as its contribution to the WHO‚Äôs Codex Alimentarius on the topic. However, as of September¬Ý2024, the implementing acts have not yet been adopted.

Insufficient EU rules on legibility

40 The FIC¬ÝRegulation requires food companies to ensure the legibility of mandatory information, for example by using certain font sizes. Food companies are faced with a situation in which there is demand from consumers and authorities for more information on food products (such as on origin or sustainability). At the same time, product packaging is being increasingly reduced partially for environmental reasons. This can impact adversely the legibility of information.

41 The FIC Regulation required the Commission to establish rules on legibility through delegated acts. Although the Commission has provided some clarifications regarding legibility in its notice on questions and answers on the application of the FIC¬ÝRegulation, it has not adopted the delegated acts. FoodDrinkEurope, which represents the EU¬Ýfood and drink industry, published its own guidance document in 2022 to help food companies ensure the legibility of information.

No EU¬Ýrules for vegetarian and vegan labels

42 Currently, no EU¬Ýrules define the terms ‚Äúvegan‚Äù or ‚Äúvegetarian‚Äù, or the criteria for a product to be suitable for vegetarians or vegans (such as thresholds for traces of animal products). Food companies producing these foods can voluntarily apply ISO¬Ýstandard 23662:2021 on food ingredients suitable for vegetarians or vegans, and there are also several voluntary private certification schemes.

43 Based on the FIC¬ÝRegulation, the Commission is supposed to adopt implementing acts on food information regarding the suitability of a food for vegetarians or vegans, but it has not done so. In the absence of EU rules for such food products, consumers can only base their decisions on the different private labels and product names.

Lack of reference intakes for specific population groups at EU level

44 The EU rules define reference energy and nutrient intakes for an average adult. There are currently no such reference intakes for other population groups, except vitamin and mineral intakes for infants and young children. Therefore, if food manufacturers want to include reference intakes on their products, they have to use the adult values (e.g. adult reference intakes on breakfast cereals targeted at children).

45 The Commission has not adopted implementing acts on reference intakes for specific population groups despite this being required by the FIC¬ÝRegulation. Pending the adoption of EU rules, member states are free to adopt national measures, which had not been done in the visited member states.

Information on labels can be confusing or misleading, and understanding of labels is not systematically tracked

46 EU¬Ýrules on food labelling require that food companies provide accurate, clear and easy-to-understand information to consumers. The information must not be confusing or misleading. We expected the Commission to:

- understand how constantly evolving labelling practices affect consumers, and take action to prevent confusing or misleading information from being presented on labels;

- track consumer needs and understanding of labels in a systematic way;

- take appropriate action, together with member states, in cases where consumers do not understand labels sufficiently well.

Constantly evolving labelling practices add complexity and can confuse or mislead consumers

47 Food companies always look for new ways to attract consumers. The authorities of the three member states we visited highlighted a number of cases where food companies‚Äô practices could be confusing or misleading. These include clean labels (related to the absence of certain elements, e.g. ‚Äúantibiotic-free‚Äù), uncertified qualities (e.g. ‚Äúfresh‚Äù, ‚Äúnatural‚Äù), misleading product names (e.g. using ‚Äúmeaty‚Äù to describe meat products) or omitting information (e.g. the word ‚Äúdefrosted‚Äù). Annex¬ÝII includes examples of these practices which could encourage consumers to buy products advertised as being healthier or better quality than they really are.

48 The EU¬Ýrules and guidelines presented in the previous section of this report do not provide a sufficiently clear basis to prevent such labelling practices. In fact, consumer organisations call for clearer rules to ‚Äúavoid deceiving consumers as to the true nature of the food and drink they purchase‚Äù. Box¬Ý2 shows an example of a product with potentially misleading labelling information.

Example of a mock product with potentially misleading labelling information

The packaging of this product depicts bananas, but the list of ingredients does not contain real bananas, only flavourings.

Source: ECA.

49 Conscious that consumers are more aware of how their purchasing habits might impact the environment, companies have also started using a multitude of environmental claims on products. A Commission study concluded that in 80¬Ý% of the cases selected, web shops or food product advertisements included these claims, and that consumers may be subject to greenwashing (the practice of marketing a product as environmentally friendly without proving those claims).

50 To address this issue, a new directive on empowering consumers for the green transition was adopted in 2024, to better inform and protect them against unfair labelling practices. On 22¬ÝMarch¬Ý2023, the Commission also published its proposal for the Green Claims Directive. These two legal acts will define the conditions for the use of sustainability labels and establish rules for their certification. Food companies will be required to substantiate environmental or green claims used on their products. The impact of these acts will only become apparent in the future.

51 Consumers are also exposed to a growing number of labels, logos and schemes which the Commission does not track systematically. In a 2013 study, the Commission identified 901¬Ývoluntary food labelling schemes regarding European agricultural food products, but this figure has not been updated. According to this study, a third of the surveyed consumers found the labels confusing and the same proportion thought they were misleading. A 2024 Commission report on sustainability labels identified more than 200 of these labels in the EU food sector. It states that 12 % of new product launches have a food-related sustainability label. Moreover, the member states we covered do not have an overview of all the different labels used on food products.

There is no systematic monitoring of consumer needs or their understanding of labels

52 Apart from some reports (2020-2023) focusing on specific aspects such as front-of-pack nutrition labels, origin labelling, digital labelling, date marking and some ad hoc consultations with consumers (e.g. Eurobarometer surveys on date marking), the Commission has not systematically monitored consumer understanding of labels, or whether food labelling rules address their needs.

53 The Commission regularly discusses food labelling with member states in different committees and expert group meetings, as well as with stakeholders (e.g. research institutes, consumer organisations, industry) in the context of advisory groups. However, our analysis of meeting documents shows that, even though certain aspects of food labelling have been discussed, consumer needs and their understanding of labels have not been regularly monitored.

54 In the three member states we covered, authorities did not monitor consumer needs or their understanding of labels on a systematic basis (see Figure¬Ý13). It is therefore not possible to determine whether consumers are adequately informed or their expectations are being met.

Figure¬Ý13¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝMonitoring of consumer needs and understanding of labels in the member states we covered

Source: ECA.

Consumers do not always understand labels, and awareness-raising campaigns are not a priority

55 The level of knowledge regarding food labelling varies from person to person, and information which might be clear to an informed consumer could be unclear to one less informed. While neither the Commission nor the member states systematically track consumer understanding of labels (see paragraphs¬Ý52 to¬Ý54), there is evidence that consumers do not always understand labels. According to interviewed consumer protection organisations and national authorities in the three member states we covered, consumers sometimes find the EU food labelling system complicated. Date marking is an example of labelling which consumers do not always understand.

56 The FIC¬ÝRegulation made two types of date marking mandatory: ‚Äúuse by‚Äù (date by which the product is no longer safe ‚Äì used for highly perishable foods) and ‚Äúbest before‚Äù (date until which the food retains its optimal quality when properly stored). A 2018¬ÝCommission study on date marking identified the following issues:

- poor legibility;

- lack of clarity on how food companies determine the dates;

- poor consumer understanding of date marking (e.g. less than half of the surveyed people understood the meaning of these dates).

57 The member states we visited confirmed that current date marking rules are not well understood by consumers. In 2019, the Commission asked the European Food Safety Authority for scientific input. On this basis, the Commission provided food companies with guidance on date marking in 2020. In the Farm to Fork strategy, the Commission announced a revision of the EU¬Ýrules on date marking by the end of 2022. The subsequent consultations showed that, while member states supported a harmonised approach ‚Äì including awareness-raising campaigns and educational programmes at EU level ‚Äì they preferred the revision of date marking to be part of a broader revision of the FIC¬ÝRegulation. However, the Commission has not yet published its legislative proposal.

58 The European Parliament called on the EU and member states to empower consumers by paying more attention to and investing more in consumer information and education campaigns ‚Äúthat target the right messages at the right consumer segment‚Äù. Educating consumers could significantly increase their understanding of food labelling. It is noteworthy, however, that the EU allocated only around ‚Ǩ5.5¬Ýmillion for food labelling awareness campaigns from 2021 to 2025.

59 In the three member states we visited, little attention is paid to information campaigns for consumers – they are sporadic and only target specific areas of interest. Italy financed an information and communication campaign to raise awareness of the NutrInform Battery initiative and build consensus in 2022. The Belgian authorities conducted a public information campaign in 2021 to improve consumer understanding of date marking. In Lithuania, the Ministry of Health carries out regular information campaigns to increase the recognition of the Keyhole label.

Control systems, sanctions and reporting are affected by weaknesses

60 EU¬Ýrules require member states to set up control systems to ensure the accuracy of food labelling information and check whether food companies implement labelling rules correctly. They also require member states both to define sanctions applicable to infringements of food labelling rules and to report food labelling issues to the Commission through different means. The Commission uses this information to monitor the application of EU food labelling rules.

61 We looked at the control systems and sanctions of member states as well as at the Commission’s and member states’ reporting on these checks. We expected:

- control systems to be set up and controls to be coordinated;

- EU labelling rules to be checked effectively;

- member states to apply dissuasive, effective and proportionate sanctions to infringements of food labelling rules;

- reporting on controls to be carried out and be useful.

Control systems are in place but there are shortcomings

62 We found that all 27¬Ýmember states have control systems in place and carry out checks on food labelling rules in accordance with annual control plans and multiannual (every 3 to 5¬Ýyears) national control plans. These plans are drawn up based on risk analysis, complaints, and ad¬Ýhoc checks on food companies.

63 Although they still carry out annual controls, five member states (Belgium, Denmark, Latvia, Malta and Slovenia) had not updated their control plans at the time of our audit. The Commission has followed this up with the member states concerned, but the issue remains unresolved.

64 The coordination of different controls in member states is essential for the system to function effectively and efficiently. The Official Controls Regulation therefore requires each member state to designate a single body tasked with coordinating the preparation of its multiannual national control plan13. We found that control systems in member states are sometimes complex and often involve multiple authorities, which may lead to inefficiencies and gaps in the control systems (see Box¬Ý3). As of September¬Ý2024, 6 out of 27¬Ýmember states had not designated a single body.

Examples of the complexity of control systems

Belgium has two competent authorities at federal level and three at regional level. In practice, one takes up a coordinating role to report to the Commission but does not have the mandate to check the coherence or completeness of the data. In 2021, the Commission concluded that the coordination between the federal and the regional authorities was inadequate and that compliance with origin labelling rules could not be checked.

Italy’s control system for checking compliance with food labelling rules includes two main competent authorities and four police forces. They each have their own planning process and perform their own risk analysis. Multiple cooperation agreements and coordination initiatives are required, given the complexity of the system and number of bodies. This entails a risk of gaps in the control system.

65 The Commission carries out audits of member states’ control systems. Its 2017 and 2018 audits in seven member states (Belgium, Greece, France, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal and Romania) had already pointed to coordination problems in some countries. Through our audit, we found that Italy has been slow to adapt its control system following the observations of the Commission and that some weaknesses remain in Belgium as well. The Commission made no observations on Lithuania.

Weak checks on voluntary information and online retail

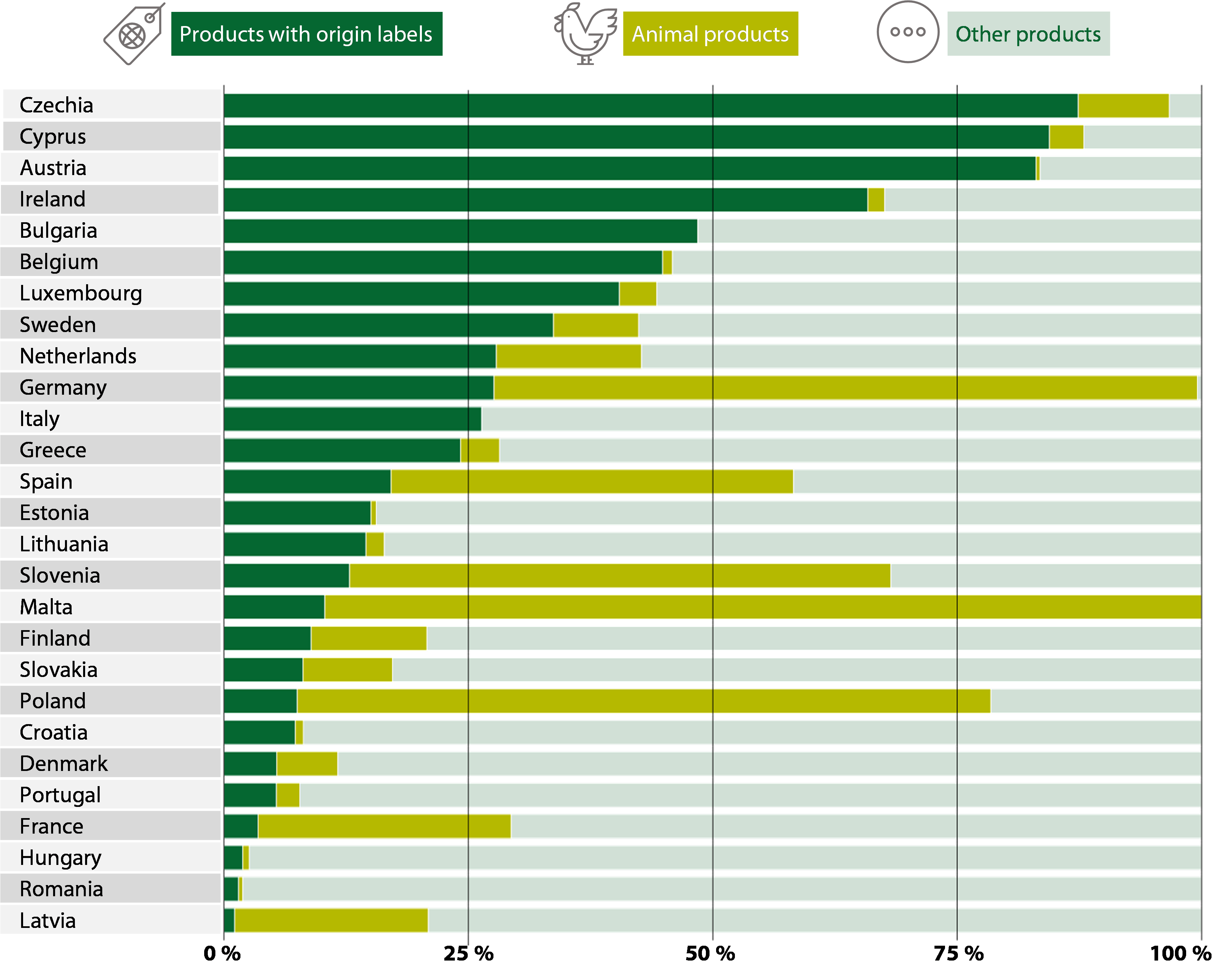

66 We analysed the 27¬Ýmember states‚Äô annual control reports for 2022 submitted to the Commission. The type of check varied significantly between member states (see Figure¬Ý14). Some member states focused their labelling checks on origin labelling, while others prioritised animal products or other products (including checks on nutrition and health claims).

Figure¬Ý14¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝOfficial controls on food labelling carried out by the member states in 2022 ‚Äì by type (%)

Source: ECA, based on member states’ annual reports for 2022.

67 Figure¬Ý15 shows the different control levels depending on the type of information on the label. Member states‚Äô checks are mostly focused on mandatory information, for example whether the ingredient list, allergens and nutrition declaration are properly displayed and readable. Evidence from the member states we visited indicates that controls on these mandatory elements work well.

Figure¬Ý15¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝDifferent levels of member states‚Äô controls on food labelling information

Source: ECA, based on audit interviews and research.

68 On the other hand, there are few or no checks on voluntary information, even though there is a general obligation to check that voluntary information complies with EU¬Ýlegislation.

69 For voluntary information, control authorities in member states focus their checks on EU-regulated quality schemes ‚Äì the labelling of organic products and products with geographical indications ‚Äì, since it is required by the Official Controls Regulation. Regarding nutrition and health claims, although regulated at EU level, we found that checks at member state level were weak (see Box¬Ý4). Authorities also check national quality schemes, such as Streekproduct (Belgium), Kokybƒó (Lithuania), or SQNPI ‚Äì National Integrated Production Quality System (Italy).

Example of weak checks on nutrition and health claims

The Commission pointed out weaknesses during its 2018 audit on nutrition and health claims in Italy. During our audit, we saw that operational checklists still do not include these claims explicitly.

During its 2018 audit in Belgium, the Commission pointed out that the authorities do not cover rules on nutrition and health claims fully. During our audit, we noticed that the general checklist for the retail sector does not include specific checks on claims, and that the nutritional value of food supplements is only checked in a limited number of cases.

70 Food companies use an increasing number of voluntary labels and claims (see paragraph¬Ý51) ‚Äì sometimes related to sustainability issues (see paragraphs¬Ý49-51) ‚Äì to advertise their products using attractive messages (e.g. images of grazing cows, illustrations of fruit, claims such as ‚Äúnatural‚Äù, ‚Äúno additives‚Äù or ‚ÄúGM-free‚Äù). While there are certification schemes with private third-party verification behind some labels, others may not be subject to any certification. Contrary to other types of voluntary labels (e.g. nutrition and health claims), food companies have no specific rules to use such labels. Member state control authorities carry out minimal checks on such labels or claims ‚Äí for example, only if there are suspicions or complaints. Consequently, the reliability of voluntary labels is not satisfactorily monitored.

71 Since the COVID-19¬Ýpandemic, all the member states we visited have observed a boost in the sale of food products via e-commerce, as well as an increased number of complaints about online stores. The three countries carry out checks of online sales. They check whether the information provided to consumers on websites (including presentation and advertising) is correct and in line with the rules. The Lithuanian authorities reported a high overall infringement rate (61.6¬Ý% in 2022) in e-commerce, which includes food products. Infringement rates in online retail are higher than in conventional retail, so consumers find more products that do not respect EU¬Ýfood labelling rules in online stores. Information on such products can be misleading and their consumption may even be unsafe.

72 Member state authorities face a number of problems when checking the online sale of food products.

- They can only impose sanctions on food companies that are registered in their country. For websites registered in other EU¬Ýmember states, they can report the issue using iRASFF, the Commission‚Äôs online application (see paragraph¬Ý09).

- Regarding websites outside the EU, it is almost impossible for authorities to control online retail. They may contact the operator directly or request follow-up action via the embassy of the third country where the operator is based. This is not always fast or effective. Italy has a more elaborate approach than the other member states we covered to checking e-commerce, which we consider to be good practice (see Figure¬Ý16).

- Food supplements are often sold through e-commerce platforms, sometimes via social media. These sales are not easy to check as they often take place through a network of small independent sellers.

- Online stores can be closed (and reopened under a different name) very quickly, for example, as soon as inspectors from the member state authority identify themselves during a check (in which case inspectors miss the opportunity to follow up on non-compliance).

Figure¬Ý16¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝItalian approach to checking e-commerce

Source: ECA.

Fines are not always dissuasive, effective or proportionate

73 The three member states we visited apply a range of sanctions on infringements of food labelling rules:

- warnings (which allow the responsible food company to correct the situation);

- fines (administrative or criminal);

- product withdrawals or recalls;

- seizure of products;

- business closure or licence revocation.

74 Our analysis focused on fines, as they are the most common type of sanction. All three member states impose them based on a number of criteria, such as the nature of the infringement, the type of company, or if it concerns a repeated infringement. Based on the interviews with the authorities of these member states and our analysis of the evidence, we found that the amount of the fines varies significantly and is sometimes low (i.e. not dissuasive) or unrelated to the severity of the infringement (i.e. not proportionate), as detailed below.

- Food labelling fines in Lithuania range from ‚Ǩ16 to ‚Ǩ600, which is low. Higher fines may apply in rare cases of misleading advertising (up to 6¬Ý% of the food companies‚Äô annual revenue in the previous financial year, up to a maximum of ‚Ǩ200¬Ý000 for repeated infringements).

- In Belgium, the average fine in the distribution sector between 2020 and 2023 was ‚Ǩ651, and ‚Ǩ1¬Ý197 in the processing industry. Infringements can be sanctioned with a fine up to ‚Ǩ80¬Ý000 (or up to 4¬Ý% of the annual turnover if this is higher, which has not yet been applied).

- In Italy, the highest fine (up to ‚Ǩ40¬Ý000) is applied to food companies selling products beyond their expiry date. Between 2020 and 2022, the average value of fines imposed by one of the competent authorities was ‚Ǩ1¬Ý717. The police can also impose fines that do not always take into account the type of company or the severity of the infringement, which means they are not proportionate.

75 Italian and Belgian authorities told us that they struggled to enforce fines, which affects their effectiveness. They also noted that, when an offender does not pay the fine and the case is brought to court, the public prosecutor often decides to close the case without further action. Since January¬Ý2024, Belgium has applied a new procedure that allows the recovery of the unpaid fine through a bailiff. The effectiveness of this system remains to be seen.

Reporting arrangements for member states on their official controls are cumbersome and their added value is not clear

76 Member states have to report to the Commission every year on their official controls, including checks on food labelling. This allows the Commission to have a systematic overview of food labelling issues. In turn, the Commission has to produce an annual summary report for the EU-27.

77 The Commission updated the reporting arrangements in 2020. According to the national authorities we interviewed in the three member states we visited, the Commission’s updated reporting template is difficult to use. This is because reporting is focused on food safety, whereas controls target other issues (e.g. food quality), or because national reporting is structured around food companies (not product groups, as in the template).

78 We reviewed the information relevant to food labelling in the 27 member states’ annual control reports. We found that many were not able to fully complete the template and preferred to provide additional information in the annexes to their reports. This complicates the information processing and analysis for the Commission.

79 The Commission acknowledges that, due to inconsistencies in the data provided by member states, there are reporting gaps in the summary report informing the public of official controls on food labelling.

80 In addition to the annual reporting on official controls, the Alert and Cooperation Network allows member state authorities to rapidly exchange information and cooperate regarding official controls in the agri-food chain. It has three components:

- the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed, for non-compliance entailing potential health risks;

- the Administrative Assistance and Cooperation Network, for non-compliance without health risks;

- the EU¬ÝAgri-Food Fraud Network, for suspicions of fraud.

81 Member states exchange information by sending notifications through iRASFF. We analysed all relevant notifications reported between 2021 and 2023 by the 27¬Ýmember states in iRASFF (see Figure¬Ý17).

Figure¬Ý17¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝShare and number of notifications related to food labelling in the three components of the database (2021-2023)

Source: ECA, based on the Alert and Cooperation Network reports and iRASFF data.

82 The number of notifications varies significantly between member states. For example, Germany was the most active, with 419¬Ýnotifications through the Administrative Assistance and Cooperation Network, whereas five member states (Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia, Portugal and Slovenia) did not send any notifications. The difference in the number of notifications can be explained partly because member states use iRASFF notifications in differing ways and have different understandings of what constitutes non-compliance. According to the Commission‚Äôs reports, claims and faulty labelling are major recurring issues reported by member states through the Alert and Cooperation Network.

83 Some member states noted that the integration of the three components of iRASFF into a single system is complicated from an organisational point of view due to the division of competences and responsibilities. The Internal Audit Service of the Commission noted in 2022 that the current architecture of the IT system is not efficient, as it requires multiple manual steps to manage notifications, and that there are issues regarding the traceability of cases and the quality of the data.

84 The Commission makes part of the information notified by member states available to the public via the RASFF Window portal, which, as a rule, does not include information that would allow a product to be identified (e.g. the name of products or companies). For example, in the case of a product recall, a consumer would be unable to find the product name on the portal. Instead, this information might be available in shops themselves (e.g. recall notification on the shelves) or through member state authorities’ information channels.

Conclusions and recommendations

85 Overall, we conclude that food labelling in the EU can help consumers make better-informed decisions when purchasing food, but there are notable gaps in the EU legal framework as well as weaknesses in the monitoring, reporting, control systems and sanctions. This leads to consumers being confronted with labels that can be confusing or misleading, or that they do not always understand.

86 We found that the EU¬Ýlegal framework provides a basis for essential information on food labels, thanks to the definition of some key concepts and the requirement to make certain information on labels mandatory (paragraphs¬Ý16-19). However, 7 out of 11 planned updates to the legal framework set out in the Food Information to Consumers Regulation (FIC Regulation) and the Claims¬ÝRegulation have not been completed. As of September¬Ý2024, the Commission had only completed work on 4 out of the 11¬Ýtopics. Furthermore, there is also pending work on origin labelling and alcoholic beverages (paragraphs¬Ý20-24). There are therefore notable gaps in the framework including the lack of a list of EU-authorised health claims on botanical products, and no EU rules for vegetarian and vegan labels. Member states have implemented different initiatives to compensate for some missing elements in the EU framework. We consider that all this limits consumers‚Äô ability to make informed choices and causes inequity in consumer access to some food-related information across the EU (paragraphs¬Ý25-45).

Recommendation¬Ý1¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝAddress the gaps in the EU¬Ýlegal framework for food labelling

The Commission should:

- urgently address pending action set out in the FIC and Claims regulations, particularly regarding topics for which the expected outcome is the adoption of a legal act (i.e. botanical claims, and precautionary allergen labelling);

- carry out further work to address outstanding issues related to origin labelling and alcoholic beverages.

Target implementation date: 2027

87 Constantly evolving labelling practices by food companies (labels, claims, images, advertising slogans, etc.) add complexity for consumers. Member state authorities highlighted potentially confusing or misleading practices. The EU¬Ýrules and guidelines do not provide a sufficiently clear basis to prevent them. Food companies also use a multitude of environmental claims on products which, when unsubstantiated, expose consumers to greenwashing. The recent and upcoming directives on empowering consumers and on green claims are expected to address this issue. Consumers are also exposed to a growing number of labels, of which neither the Commission nor the selected member states have an overview (paragraphs¬Ý46-51).

Recommendation¬Ý2¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝStep up efforts to analyse labelling practices

The Commission should:

- proactively and regularly analyse labelling practices to which consumers are exposed;

- together with member states, improve guidance for food companies.

Target implementation date: 2027

88 The Commission and member states did not monitor consumer needs or their understanding of labels on a systematic basis. It is therefore not possible to determine whether consumers are adequately informed or their expectations are being met (paragraphs¬Ý52-54).

89 Consumers do not always understand labels and sometimes find the EU¬Ýfood labelling system complicated. Even mandatory information such as date marking is not always easy to understand. We found that information campaigns for consumers carried out by member states are sporadic (paragraphs¬Ý55-59).

Recommendation¬Ý3¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝMonitor consumer expectations and take action to improve their understanding of food labelling

The Commission should:

- together with member states, systematically monitor consumer needs and their understanding of food labels;

- support member states in their efforts to improve consumer understanding of food labelling, for example by awareness-raising campaigns or a guide on food labelling for consumers.

Target implementation date: 2027

90 We found that all 27¬Ýmember states have control systems in place and carry out checks on food labelling rules as per their annual control plans and multiannual national control plans. The latter are not always up to date, and we found that in the three member states we covered there is scope to further improve the coordination of controls (paragraphs¬Ý62-65).

91 Controls work well for mandatory elements of food labelling but are very limited ‚Äì and occasionally non-existent ‚Äì for voluntary information. Furthermore, there is no realistic way for consumers to distinguish between thoroughly checked mandatory information, and voluntary information which includes varying degrees of reliability (paragraphs¬Ý66-70).

92 There are only limited checks for online retail, although sales are increasing. These checks are difficult to carry out when sales are concluded through websites registered in the EU, and almost impossible when they involve non-EU countries. Italy, one of our selected member states, has a more elaborate approach than the other member states we covered to checking e-commerce, which we consider to be good practice (paragraphs¬Ý71-72).

93 All three selected member states applied sanctions to infringements of food labelling rules, with fines of varying amounts. We found that these fines were not always dissuasive, effective or proportionate (paragraphs¬Ý73-75).

Recommendation¬Ý4¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝStrengthen member states‚Äô checks on voluntary labels and online retail

The Commission should encourage member states to strengthen their checks on voluntary labels and online retail by providing guidance and examples of good practice.

Target implementation date: 2027

94 Overall, reporting arrangements are cumbersome and their added value is not clear. Member states report annually to the Commission on their official controls. Some member state authorities were not able to fully complete the Commission‚Äôs reporting template. The Commission acknowledged that, due to inconsistencies in the data relevant to food labelling controls provided by member states, there are reporting gaps in its summary report (paragraphs¬Ý76-79).

95 Member states also exchange information on food labelling issues by sending notifications through the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed online application. The Commission acknowledges that there are issues regarding the quality of the data. Part of this application is available to the public, but, as a rule, does not include information that would allow a product to be identified (e.g. the name of products or companies). This makes it hard for consumers to use the portal to find out about issues relating to food safety and change their purchasing habits accordingly (paragraphs¬Ý80-84).

Recommendation¬Ý5¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝImprove reporting on food labelling

The Commission should:

- improve the consistency of the data reported by member states on controls relevant to food labelling, including by streamlining member states’ reporting arrangements;

- when updating the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed online application, improve the quality of data and increase information sharing on food labelling issues with the public.

Target implementation date: 2027

This report was adopted by Chamber I, headed by Ms Jo√´lle Elvinger, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 25¬ÝSeptember¬Ý2024.

For the Court of Auditors

Tony Murphy

President

Annexes

Annex¬ÝI ‚Äì¬ÝTopics for improvement mentioned in the FIC and Claims regulations

Topic | Legal reference | Target date | Expected output | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Nutrient profiles | Art.¬Ý4(1) ‚Äí Claims | 19¬ÝJanuary¬Ý2009 | Nutrient profiles and the conditions for the use of nutrition or health claims for foods as regards their nutrient profiles | Pending |

Health claims | Art.¬Ý13(3) ‚Äí Claims | 31¬ÝJanuary¬Ý2010 | List of permitted claims and all necessary conditions for their use | Partly done; pending for botanical claims |

Legibility | Art.¬Ý13(4) ‚Äí FIC | - | Delegated acts | No action |

Mandatory nutrition declaration and list of ingredients for alcoholic beverages | Art.¬Ý16 ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2014 | Report Legislative proposal (if appropriate) | Report done Proposal for wine done |

Mandatory origin labelling (i) for swine, sheep, goat and poultry meat, and (ii) where the origin of food is given but is not the same as that of its primary ingredient | Art.¬Ý26(2)(b), and Art.¬Ý26(3) ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2013 | Implementing acts | Done |

Mandatory origin labelling for meat (other than beef, swine, sheep, goat and poultry); milk and milk used as an ingredient in dairy products; unprocessed foods; single ingredient products; and ingredients representing >¬Ý50¬Ý% of a food | Art.¬Ý26(5) ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2014 | Reports to the European Parliament and the Council | Done |

Proposals to modify the relevant EU¬Ýprovisions (potentially) | Not applicable | |||

Mandatory indication of origin for meat used as an ingredient | Art.¬Ý26(6) ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2013 | Report to the European Parliament and the Council | Done |

Proposals to modify the relevant EU¬Ýprovisions (potentially) | Not applicable | |||

Presence of trans fats in foods and in the overall diet of the EU population | Art. 30(7) ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2014 | Report Legislative proposal (if appropriate) | Done |

Additional ways of presenting the energy value and the amount of nutrients | Art.¬Ý35(5) ‚Äí FIC | 13¬ÝDecember¬Ý2017 | Report to the European Parliament and the Council | Done |

Proposals to modify the relevant EU¬Ýprovisions (potentially) | Pending | |||

Traces of substances causing allergies or intolerances | Art.¬Ý36(3)(a) ‚Äí FIC | - | Implementing acts | Pending |

Suitability of a food for vegetarians or vegans | Art.¬Ý36(3)(b) ‚Äí FIC | - | Implementing acts | No action |

Reference intakes for specific population groups | Art.¬Ý36(3)(c) ‚Äí FIC | - | Implementing acts | No action |

Absence or reduced presence of gluten | Art.¬Ý36(3)(d) ‚Äí FIC | - | Implementing acts | Done |

Annex¬ÝII ‚Äì Examples of labelling practices that could mislead consumers

Type of labelling | Examples | Description |

|---|---|---|

Related to the absence of certain elements | No additives No preservatives Antibiotic-free | “Clean” labelling is related to the absence of certain elements (e.g. “antibiotic-free”). This can be used by food companies as a marketing tool because some consumers search for natural, less-processed foods that do not contain synthetic additives and are therefore considered a healthier option. EU rules do not lay down specific conditions for the use of claims such as “No additives” or “No preservatives” but this information should comply with the general FIC Regulation requirements (i.e. to be accurate, not to mislead or confuse consumers). |

Related to uncertified qualities | Fresh Natural Whole grain | The claim “natural” is often used by food companies as a marketing tool since it highlights a positive aspect. However, this claim has no official definition, except in the context of the Flavourings Regulation (e.g. “natural vanilla flavouring”) and the Claims Regulation (e.g. “naturally high in fibre”). Some food companies tend to make their products seem healthier than they really are, which is misleading. For example, there are no rules regarding the minimum level of whole grains a food must contain to use the term “whole grain” except for the requirement of a quantitative indication. |

Omission of information | Alcohol-free Omitting the word ‚Äúdefrosted‚Äù | There is no harmonised approach to informing EU consumers that products contain some alcohol, instead national rules may apply. EU law does not define alcohol-free beverages. Based on customs rules, in Belgium, beer with <¬Ý0.5¬Ý% alcohol content may be sold as alcohol-free beer (whereas this is 0.1¬Ý% in the Netherlands and 1.2¬Ý% in France and Italy). This can confuse consumers that do not want to consume any alcohol for health or religious reasons. EU¬Ýrules state that foods that have been frozen and which are sold defrosted need to mention ‚Äúdefrosted‚Äù on their packaging, except when thawing does not pose risks (e.g.¬Ýproducts such as butter). Member state authorities indicated that it is not always clear when this exemption can be applied, despite the existence of EU rules. |

Related to the product name | Using “meaty” to describe meat products | Lithuanian authorities noted that sometimes the way products are described can be misleading. For example, using “meaty” to imply that a meat product such as a sausage has special characteristics, even though this is an inherent attribute of the product. This practice is prohibited by the FIC Regulation. |

Source: ECA analysis.

Annex¬ÝIII ‚Äì Types of front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes in the EU and UK

Taxonomies put forward in the literature | Examples | Developer | Member state | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nutrient-specific | Numerical Non-directive Reductive (non-interpretative) | Reference Intakes |

| Private | Across the EU | |

NutrInform Battery |

| Public | Italy | |||

Colour-coded Semi-directive Evaluative (interpretative) | UK Front of Pack |

| Public | UK | ||

Summary labels | Positive logos (endorsement) | Directive Evaluative (interpretative) | Keyhole |

| Public | Denmark, Lithuania, Sweden |

Heart/Health logos |

| NGO Public | Finland, Slovenia Croatia | |||

Graded indicators | Nutri-Score |

| Public | Belgium, Germany, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands | ||

Source: ECA, based on the report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council regarding the use of additional forms of expression and presentation of the nutrition declaration (COM(2020)¬Ý207¬Ýfinal).

Abbreviations

FIC: Food Information to Consumers

RASFF: Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed

WHO: World Health Organization

Audit team

The ECA’s special reports set out the results of its audits of EU policies and programmes, or of management-related topics from specific budgetary areas. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to be of maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by Audit Chamber I ‚Äì Sustainable use of natural resources, headed by ECA Member Jo√´lle¬ÝElvinger. The audit was led by ECA Member Keit¬ÝPentus¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝRosimannus, supported by Annikky¬ÝLamp, Head of Private Office and Daria¬ÝBochnar, Private Office Attach√©; Florence¬ÝFornaroli, Principal Manager; Aris¬ÝKonstantinidis, Head of Task; Marie¬ÝElgersma, Jolita¬ÝKorzuniene and Els¬ÝBrems, Auditors; Evelyn Hoffmann, trainee. Zoe¬ÝAmador, Paola¬ÝMagnanelli and Viktorija¬Ý≈Ýableviƒçi≈´tƒó provided linguistic support. Marika¬ÝMeisenzahl provided graphical support. Judita¬ÝFrange≈æ provided secretarial support.

From left to right: Marie¬ÝElgersma, Aris¬ÝKonstantinidis, Annikky¬ÝLamp, Keit¬ÝPentus¬Ý‚Äì¬ÝRosimannus, Florence¬ÝFornaroli, Daria¬ÝBochnar and Jolita¬ÝKorzuniene.

COPYRIGHT

© European Union, 2024

The reuse policy of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is set out in ECA Decision No¬Ý6-2019 on the open data policy and the reuse of documents.

Unless otherwise indicated (e.g. in individual copyright notices), ECA content owned by the EU is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC¬ÝBY¬Ý4.0) licence. As a general rule, therefore, reuse is authorised provided appropriate credit is given and any changes are indicated. Those reusing ECA content must not distort the original meaning or message. The ECA shall not be liable for any consequences of reuse.

Additional permission must be obtained if specific content depicts identifiable private individuals, e.g. in pictures of ECA staff, or includes third-party works.

Where such permission is obtained, it shall cancel and replace the above-mentioned general permission and shall clearly state any restrictions on use.

For any use or reproduction of elements that are not owned by the EU, permission may need to be sought directly from the respective right holders. The EU does not own the copyright and/or trademark in relation to the following elements:

Resources from different copyright holders have been used to design the visuals contained in the following figures and box:

Figure 3: ¬©¬Ýstock.adobe.com/ wisannumkarng, Vlad Klok, FotoIdee.

Figure 7, 14 and 16: Flaticon.com ¬©¬ÝFreepik Company S.L. All rights reserved.

Figure 8: ¬©¬Ýstock.adobe.com/ Pilawan.

Figure 10: (mock up cookies) ¬©¬Ýstock.adobe.com/ castecodesign, Giordano Aita, ludmila_m; (chocolate bar) ¬©¬Ýstock.adobe.com/ castecodesign, Anastasi17.

Box 3: ¬©¬Ýstock.adobe.com/ VectorBum.

Logos/trademarks from different right holders have been used in the different parts of the report:

NutriScore (figures 3, 11, 12 and annex III).

Healthy Living, Heart Symbol and Protective Food Symbol (figure 11 and annex III).

Keyhole and Nutrinform Battery (figure 11, 12 and annex III).

EU Organic logo, Geographical indications logos, Kokybƒó, Streekproduct, Fairtrade and Climate neutral certification (figure 15).

Reference Intakes and UK Front-of-Pack (annex III).

Software or documents covered by industrial property rights, such as patents, trademarks, registered designs, logos and names, are excluded from the ECA’s reuse policy.

The European Union’s family of institutional websites, within the europa.eu domain, provides links to third-party sites. Since the ECA has no control over these, you are encouraged to review their privacy and copyright policies.

Use of the ECA logo

The ECA logo must not be used without the ECA’s prior consent.

| ISBN 978-92-849-3079-1 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/1182425 | QJ-01-24-005-EN-N | |

| HTML | ISBN 978-92-849-3080-7 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/8152493 | QJ-01-24-005-EN-Q |

Endnotes

1 Article 2 of Regulation (EU) No¬Ý1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25¬ÝOctober¬Ý2011 on the provision of food information to consumers.

2 Article¬Ý169 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

3 Regulation¬Ý(EC) No¬Ý178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28¬ÝJanuary¬Ý2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law.

4 Regulation (EC) No¬Ý1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20¬ÝDecember¬Ý2006 on nutrition and health claims.

5 Articles¬Ý7 and 36 of Regulation (EU) No¬Ý1169/2011.

6 Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15¬ÝMarch¬Ý2017 on official controls.

7 Special report 02/2019, paragraphs 46-69.

8 Special report 04/2019, paragraph 89.

9 Special report 34/2016, paragraphs 67-69.

10 Review 03/2023, paragraphs 29-36.

11 Commission Implementing Regulation¬Ý(EU) No¬Ý828/2014 of 30¬ÝJuly¬Ý2014 on the requirements for the provision of information to consumers on the absence or reduced presence of gluten in food.

12 Regulation (EU) 2021/2117 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2¬ÝDecember 2021.

13 Article¬Ý109 of Regulation¬Ý(EU)¬Ý2017/625.